Chema Madoz (b. 1958, Madrid, Spain) is a distinguished figure in contemporary photography, widely known for his black-and-white, conceptual images that explore the surreal potential of everyday objects. His work transcends traditional boundaries of photography, often viewed as visual poetry that manipulates objects to create new meanings. Madoz's work draws heavily on the influence of Surrealism, Dadaism, and Minimalism, positioning him as a unique artist who challenges viewers to reconsider the mundane through a lens of transformation and abstraction.

Chema Madoz, born José María Rodríguez Madoz, developed an early interest in photography during his time studying Art History at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid in the late 1970s. This academic foundation, coupled with his practical photography courses at the Image Teaching Center (C.E.I.), helped shape his formalist approach to art. Madoz was initially influenced by traditional black-and-white photography but soon began to experiment with objects and compositions that would define his mature style.

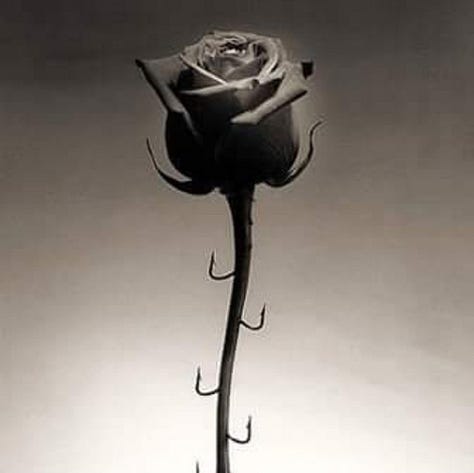

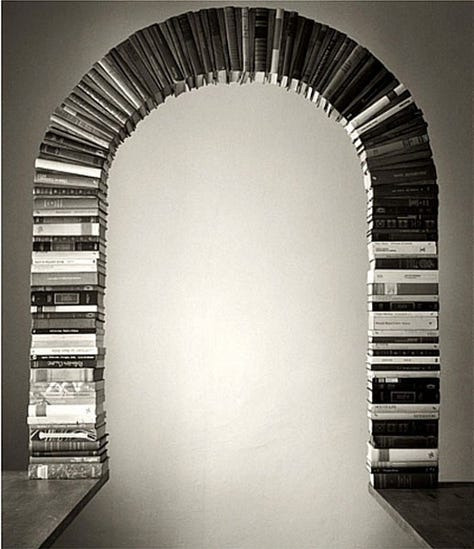

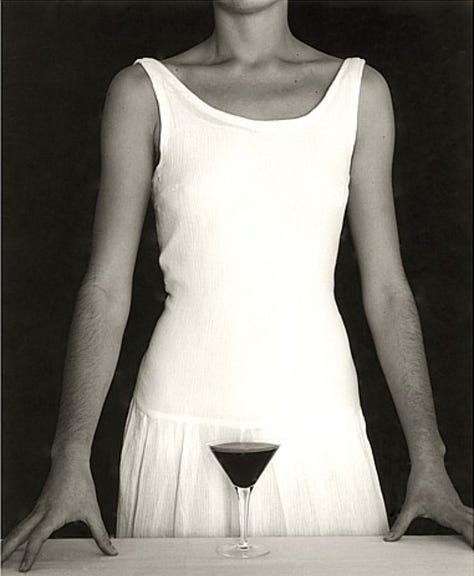

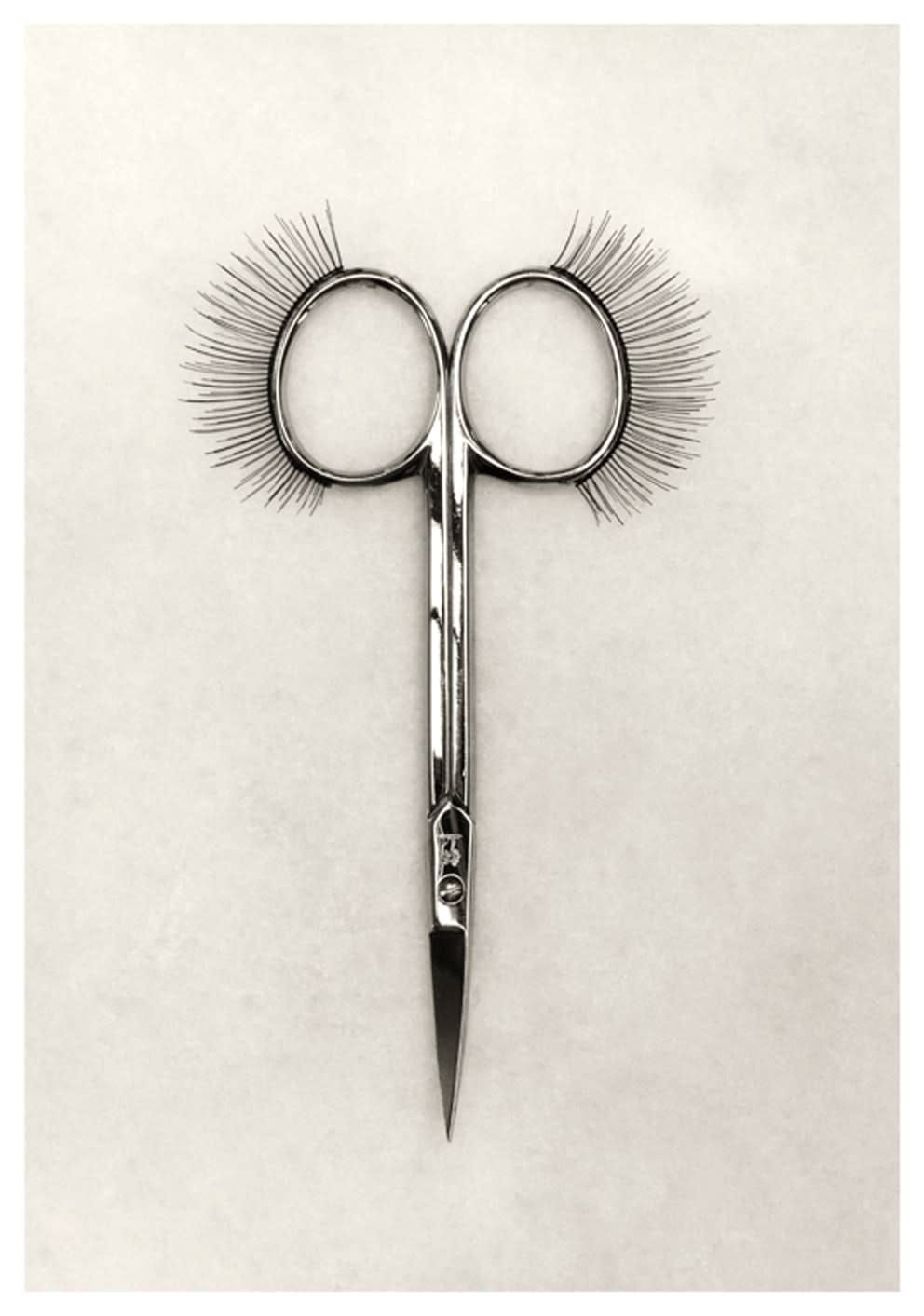

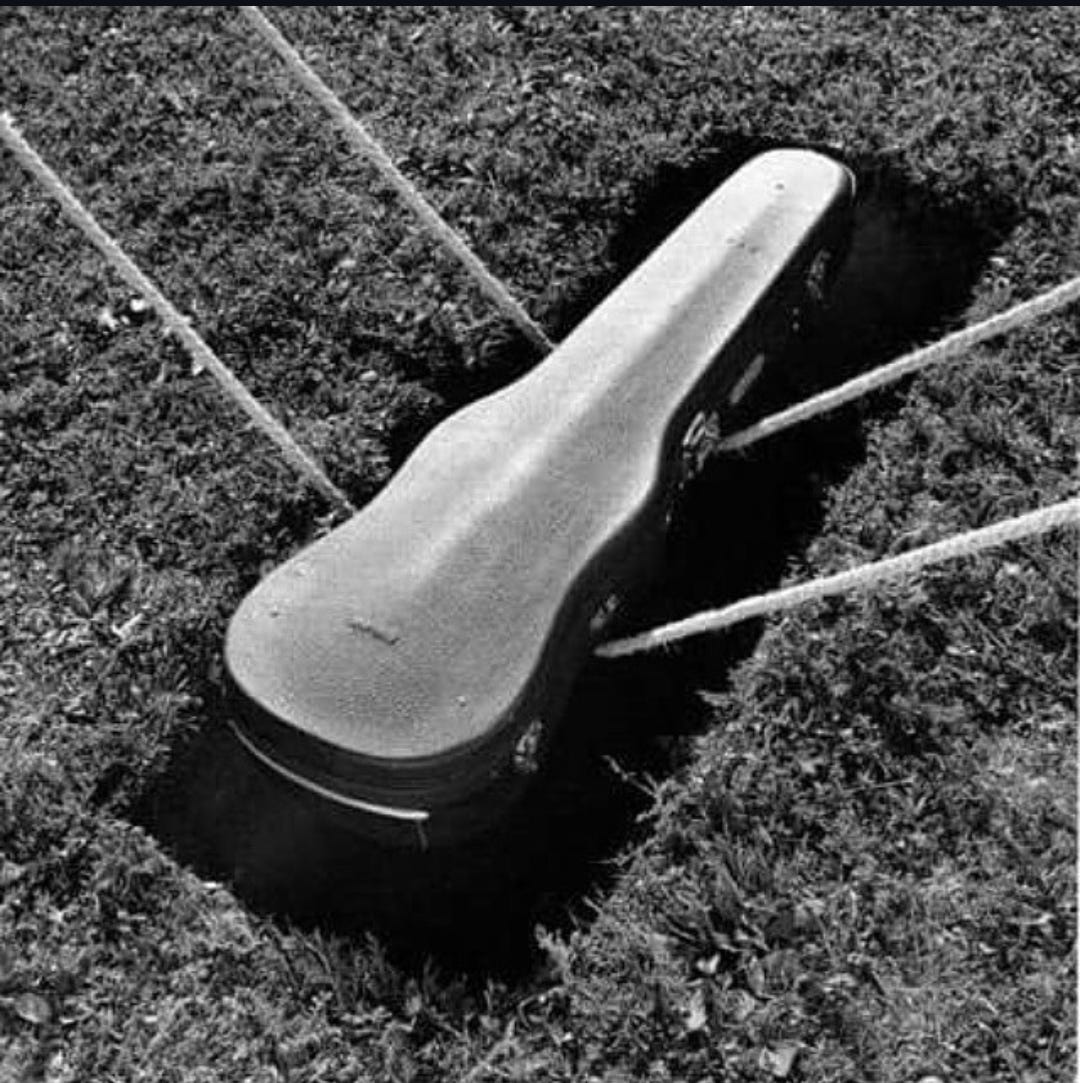

Madoz’s photography is characterized by a meticulous arrangement of everyday objects in unconventional and thought-provoking ways. He does not alter his photographs digitally; instead, he relies on analog techniques to capture objects in their most natural form. His process typically involves manipulating or combining items in ways that evoke surreal associations, creating a visual pun or metaphor.

For instance, Madoz’s iconic image of a birdcage whose bars are replaced by barbed wire speaks to themes of confinement, nature, and control. This juxtaposition of familiar objects in unfamiliar contexts forces the viewer to question the intrinsic meaning of the objects and their new relationships. As critic Daniel Giralt-Miracle notes, "Madoz’s images go beyond mere visual trickery; they engage the viewer in a process of discovery and intellectual engagement" (Giralt-Miracle, 2013).

Madoz's work is often linked to Surrealism, especially the photography of Man Ray and René Magritte’s paintings. However, Madoz takes a minimalist approach, stripping his compositions down to a single or a few objects, devoid of any background distractions. This attention to form and simplicity aligns him more closely with the principles of Minimalism and Conceptual Art. Madoz himself has acknowledged the influence of the Surrealists but maintains that his work is more about creating visual poetry than adhering to the Surrealist pursuit of the unconscious. As he explains, "I prefer to work from the world of objects, which always suggest ideas, rather than from dreams" (Madoz, 2011).

His work also resonates with the Dada movement, particularly in its use of readymades—ordinary objects elevated to the status of art through their recontextualization. Like Marcel Duchamp, Madoz presents objects in such a way that their inherent function is called into question, though Madoz's approach is often more delicate and subtle.

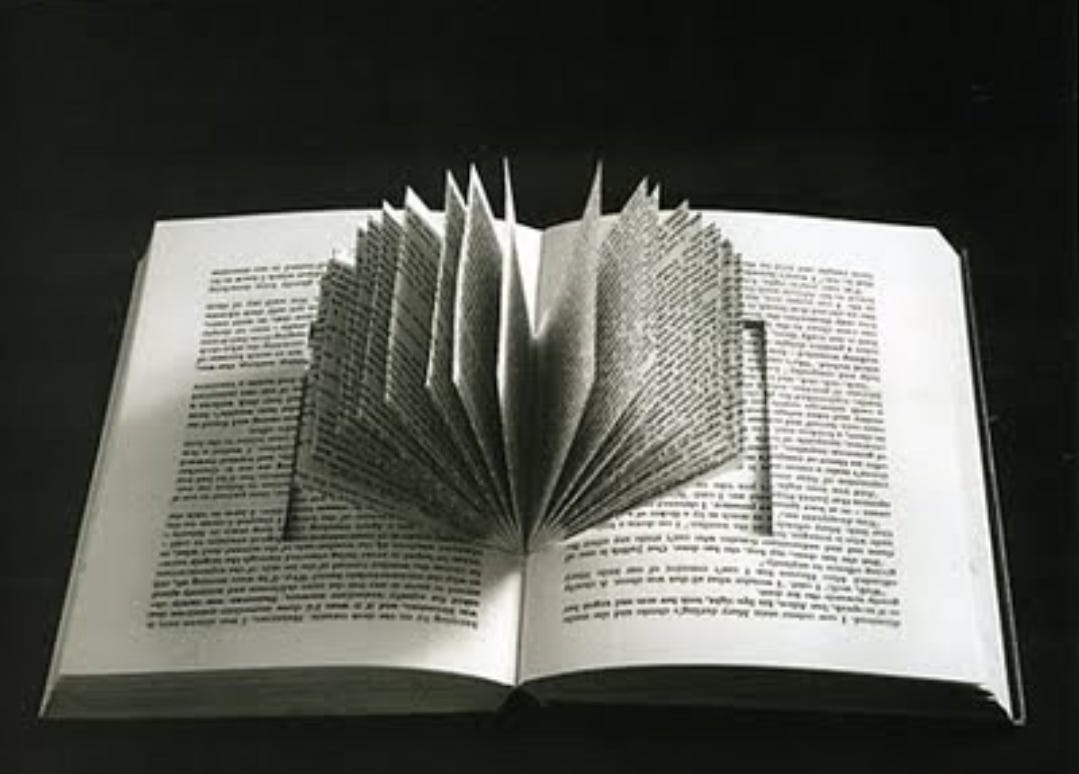

Several recurring themes dominate Madoz's oeuvre, including duality, transformation, and paradox. His manipulation of objects often results in images that embody two opposing concepts simultaneously, such as freedom and constraint, fragility and strength, or nature and industry. This thematic duality is evident in his 1999 photograph of eyelashes paired with a pair of scissors—an image that evokes both delicacy and destruction.

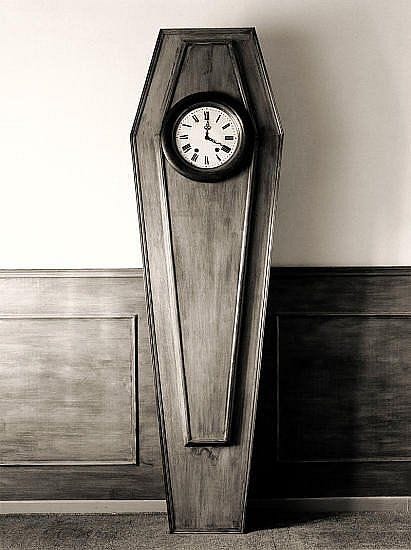

Madoz’s work also explores the concept of time and temporality, particularly in images that suggest a fleeting moment or an impending change. A famous example is his photograph of a coffin with a clock face embedded in it's top, a symbol of our mortality.

Madoz's photography has been widely acclaimed in both European and international art circles. His first major exhibition was in 1983 at the Royal Photographic Society of Madrid, and since then, his work has been exhibited at institutions such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Madrid and the Reina Sofía Museum. In 2000, Madoz became the first photographer to receive Spain's prestigious National Photography Award, solidifying his place in the canon of contemporary photography.

Art historian Oliva María Rubio describes Madoz’s work as “an exploration of the poetic potential of objects” (Rubio, 2006). Critics have praised his ability to challenge the viewer’s perceptions without relying on overt symbolism or complex narratives. Madoz’s minimalist approach to form and composition has earned him comparisons to modernist photographers like André Kertész and contemporary conceptual artists like John Baldessari.

Despite this acclaim, some critics argue that Madoz’s work, while visually striking, can at times lean too heavily on its conceptual foundation, leaving less room for emotional depth. However, as art historian Rafael Doctor Roncero points out, “The emotional resonance of Madoz’s work lies in its subtlety; his images reveal their meaning slowly, through contemplation, rather than immediately” (Roncero, 2014).

Chema Madoz has carved out a unique niche within the world of contemporary photography by transforming everyday objects into thought-provoking works of art. His conceptual approach, influenced by Surrealism, Minimalism, and Dada, challenges viewers to reconsider the meanings of the objects around them. Through his meticulous compositions, Madoz encourages a slow, contemplative engagement with his images, allowing viewers to uncover layers of meaning over time. As his work continues to be exhibited and studied, Madoz remains a seminal figure in the exploration of visual perception and the poetic potential of the everyday.

References

Giralt-Miracle, Daniel. The Poetics of Chema Madoz. Madrid: La Fábrica, 2013.

Madoz, Chema. Interview with El País. October 5, 2011.

Roncero, Rafael Doctor. Visual Poetry: The Photography of Chema Madoz. Madrid: Fundación Telefónica, 2014.

Rubio, Oliva María. Chema Madoz: Obra Fotográfica. Madrid: Fundación MAPFRE, 2006.