Charles Loloma (1921–1991) was a pioneering Hopi artist who dramatically transformed Native American jewelry-making and contributed to the global art movement of the 20th century. Through his innovative techniques and exploration of modernist design principles, Loloma redefined the aesthetic and cultural boundaries of Native American art. His groundbreaking approach to materials, use of symbolic elements, and fusion of traditional Hopi culture with contemporary art movements marked a turning point in Native American visual arts.

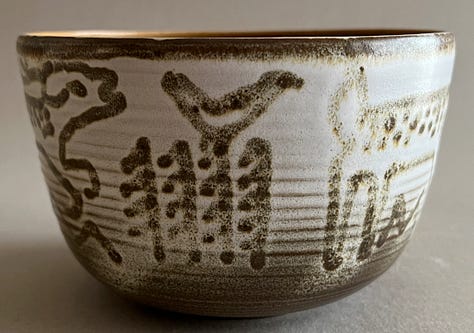

Loloma was born in Hotevilla, Arizona, a Hopi village located on the Hopi Reservation, and his early experiences in this culturally rich environment deeply influenced his artistic development. He was exposed to Hopi ceremonial life, symbols, and rituals from a young age. At the Santa Fe Indian School, Loloma studied under Dorothy Dunn, who emphasized traditional Native American art forms rooted in regional iconography and symbolism. This early training helped to shape his deep connection to his heritage.

After serving in World War II, Loloma further developed his artistic skills by attending Alfred University’s School for American Craftsmen in New York. Here, he encountered modernist design principles, particularly those of artists such as Pablo Picasso, who influenced his thinking about the possibilities of form and material in art. This exposure to modernist ideas, alongside his traditional training, laid the foundation for Loloma’s future works, where he would merge his Hopi heritage with cutting-edge artistic techniques.

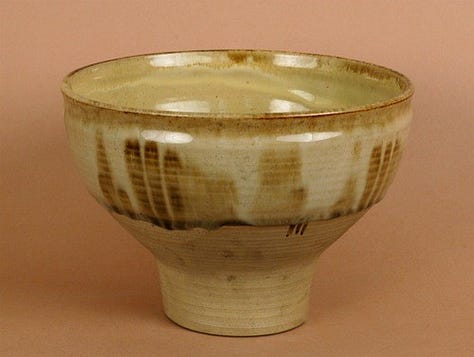

Loloma’s career as an artist began in ceramics, but by the mid-1950s, he began to focus on jewelry-making, a decision that would change the course of his life and the history of Native American art. While Hopi jewelry was traditionally crafted using turquoise and silver in relatively simple designs, Loloma revolutionized the field by incorporating a wide range of materials such as ivory, fossilized wood, coral, and lapis lazuli. These materials, which had never before been used in Hopi jewelry, symbolized the artist’s desire to break free from the constraints of traditional forms.

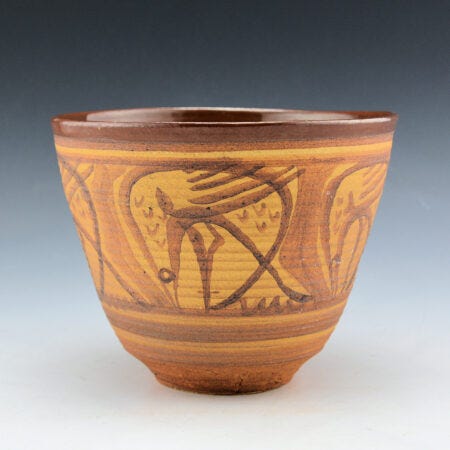

Loloma’s jewelry designs were notable for their complexity and boldness. He introduced new techniques, including the use of inlaid gemstones set in geometric patterns that evoked the landscapes, architecture, and spiritual motifs of Hopi culture. The designs were not just decorative but conveyed deeper meanings related to Hopi cosmology and ceremonial practices. For example, his use of inlaid stones was often symbolic of the four cardinal directions, a key concept in Hopi spirituality.

Loloma was deeply committed to the idea that Native art could evolve while still reflecting traditional values. He argued that modern Native American artists should not be confined to past conventions but should engage with new materials and ideas to express their cultural identity in a contemporary context. His use of non-Hopi materials, such as coral and lapis lazuli, attracted criticism from some traditionalists within his community, who viewed it as a betrayal of Hopi traditions. Nevertheless, Loloma believed that the true essence of Hopi art lay in its ability to adapt and change while remaining true to its spiritual and cultural roots.

Loloma’s work was a fusion of modernism and Hopi symbolism. His approach to blending the two was not simply about aesthetic experimentation but about creating a new language that could communicate the ongoing evolution of Hopi culture. In this way, Loloma positioned himself as both an innovator and a custodian of Hopi heritage, showing that contemporary Native American art could be both deeply rooted in tradition and in dialogue with modern artistic movements.

Loloma’s contributions went beyond his artistic work. He was an educator, dedicated to mentoring the next generation of Native American artists. He taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe and at Arizona State University in Sedona, where he shared his techniques and philosophy with aspiring artists. His mentorship helped to inspire many young Native American jewelers and artists, who adopted his approach of blending tradition with innovation.

His impact was not limited to the Native American art community. Loloma’s work was featured in major museums and exhibitions worldwide, and he was instrumental in elevating Native American jewelry from a craft to a respected form of fine art. His jewelry was included in prestigious collections such as those at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, and the Indian Arts and Crafts Board.

One of Loloma’s most significant exhibitions was the 1968 show The Art of the American Indian: 20th Century, which included his jewelry alongside works by other notable Native American artists. This exhibition helped to establish Loloma as a key figure in the broader 20th-century art world. Additionally, Loloma’s work was featured in various high-fashion shows, further bridging the gap between Native art and the global art world.

Charles Loloma’s work revolutionized the perception of Native American jewelry and art. Prior to his innovations, Native American jewelry was often seen primarily as a craft, with few individuals considering it in the same light as contemporary fine art. Loloma’s use of modernist techniques and non-traditional materials changed this perception, leading to a reassessment of what Native American art could be.

Loloma’s influence extended beyond jewelry. He demonstrated that Native American artists could work within and contribute to global art movements while maintaining a distinct cultural identity. His legacy continues to inspire contemporary Native artists, who follow his example by fusing traditional forms with modern techniques. His vision of Native art as an evolving and dynamic field remains a touchstone for artists and collectors alike.

Charles Loloma was a true revolutionary in the world of Native American art. His pioneering work in jewelry-making, his ability to merge tradition with modernism, and his commitment to cultural innovation ensured that his art would have a lasting impact. Today, Loloma’s legacy is celebrated worldwide, and his influence continues to shape the future of Native American art.

References:

Charles Loloma: Master of Native American Jewelry, The Museum of Arts and Design.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Charles Loloma Collection.

Barton Wright, Hopi Silver: The History and Hallmarks of Hopi Silversmithing (Northland Publishing, 1989).

J.C.H. King, Beyond Tradition: Contemporary Indian Jewelry (British Museum Press, 1991).