In the shadow of World War I’s unprecedented carnage, a new breed of artists rose to reject the ethical, political, and aesthetic foundations they held responsible for global catastrophe. Beginning in Zurich in 1916, Dada transformed art into a weapon of absurdity and chance, challenging bourgeois norms through anti‑art gestures such as sound poetry, ready‑mades, and photomontage (“Dada”) and Ball; Tzara). By the mid‑1920s, Dada’s international enclaves had dispersed, but its tactics, provocation, appropriation, and institutional critique, had already seeded the birth of Surrealism in Paris, a movement dedicated to reconciling dream and reality via Freudian automatism and uncanny imagery (Breton; Harris and Zucker). Together, these intertwined avant‑gardes reshaped modern art’s possibilities, redefining the artist’s role as both cultural mischief‑maker and visionary explorer of the unconscious.

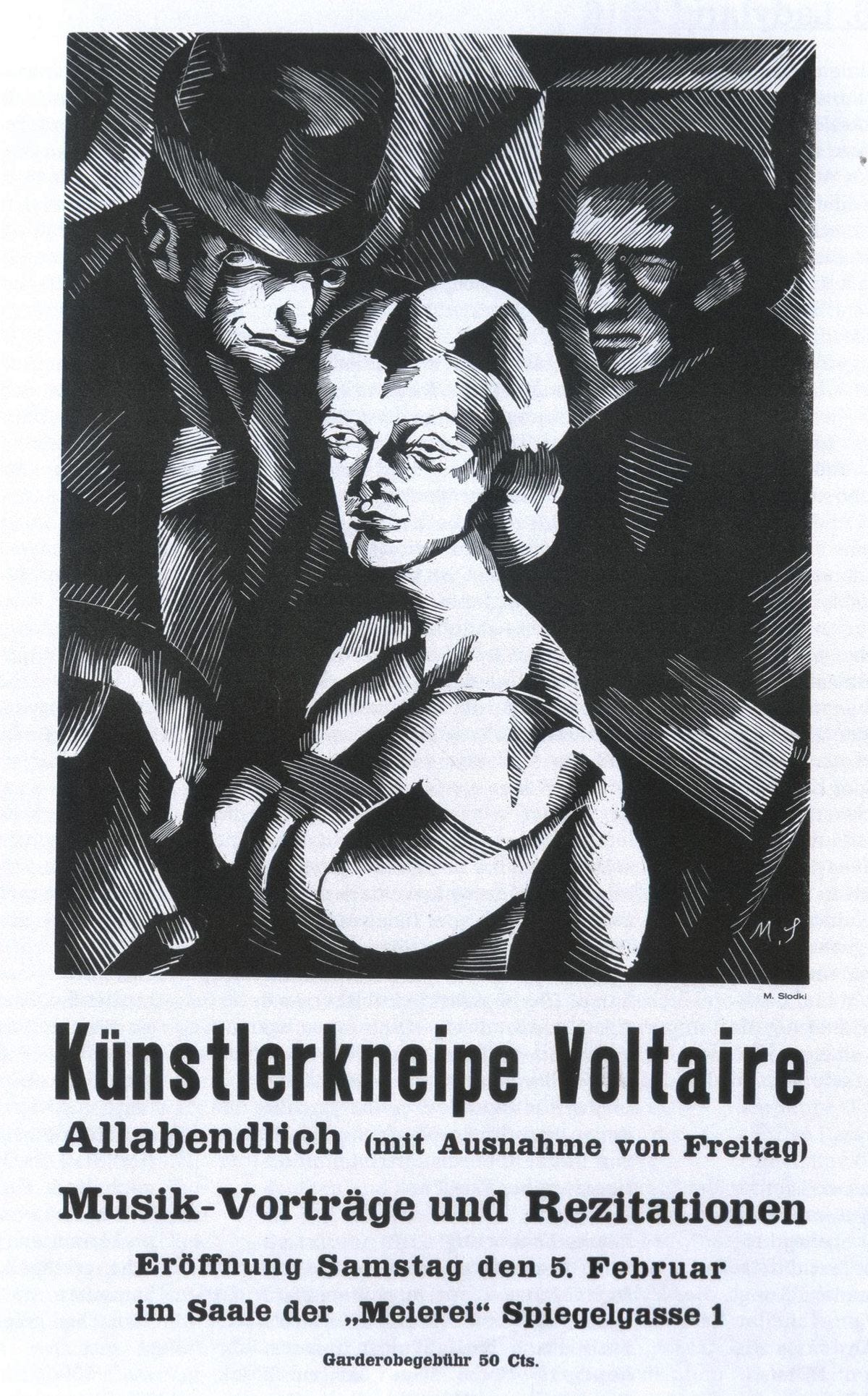

In February 1916, Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings founded the Cabaret Voltaire in neutral Zurich as a refuge for émigré intellectuals and disillusioned artists (Ball). There, Ball’s seminal sound poem Karawane dissolved language into pure sonic onomatopoeia, asserting that meaning itself could, and should, be subverted by whimsy (Ball). The performers cemented Dada’s ethos of chance by selecting their very name, “Dada”, with a knife thrust into a French‑German dictionary, foregrounding the movement’s embrace of arbitrariness (Tzara). Under this banner of playful revolt, Dada declared art an act of political provocation rather than a refuge of aesthetic harmony (“Dada”) and forged a template for later anti‑art gestures.

Central to Dada’s insurgency was the concept of “anti‑art,” whereby ordinary objects, errors, and accidents were exalted above traditional craftsmanship and beauty (“Dada”). Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a standard porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt”, epitomized this challenge to artistic authority, scandalizing the Society of Independent Artists and forcing institutions to confront their own gatekeeping (Duchamp; Talbot). Duchamp’s earlier Bicycle Wheel (1913) similarly redefined the artist’s role as nominator rather than maker, arguing that designation alone could confer artistic status (Talbot). Concurrently, Tristan Tzara’s 1918 manifesto exhorted poets to abandon syntax and logic in favor of chance operations; methods that would later underpin Surrealist automatism (Tzara).

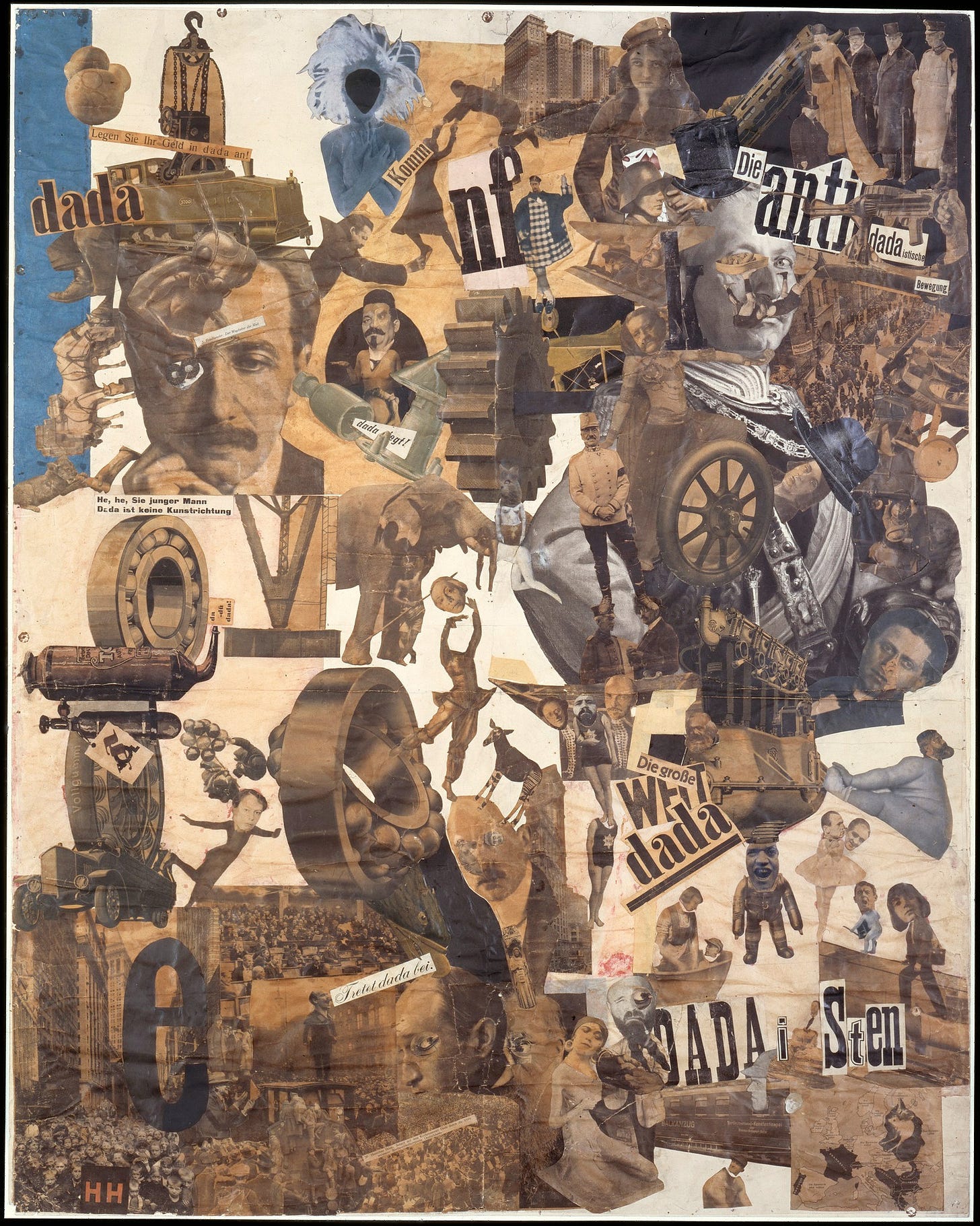

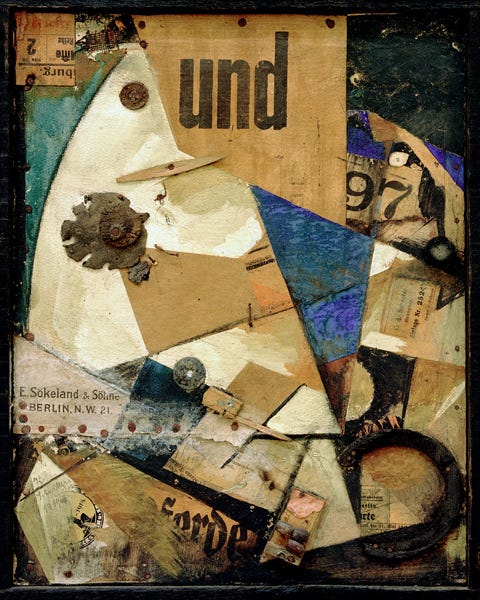

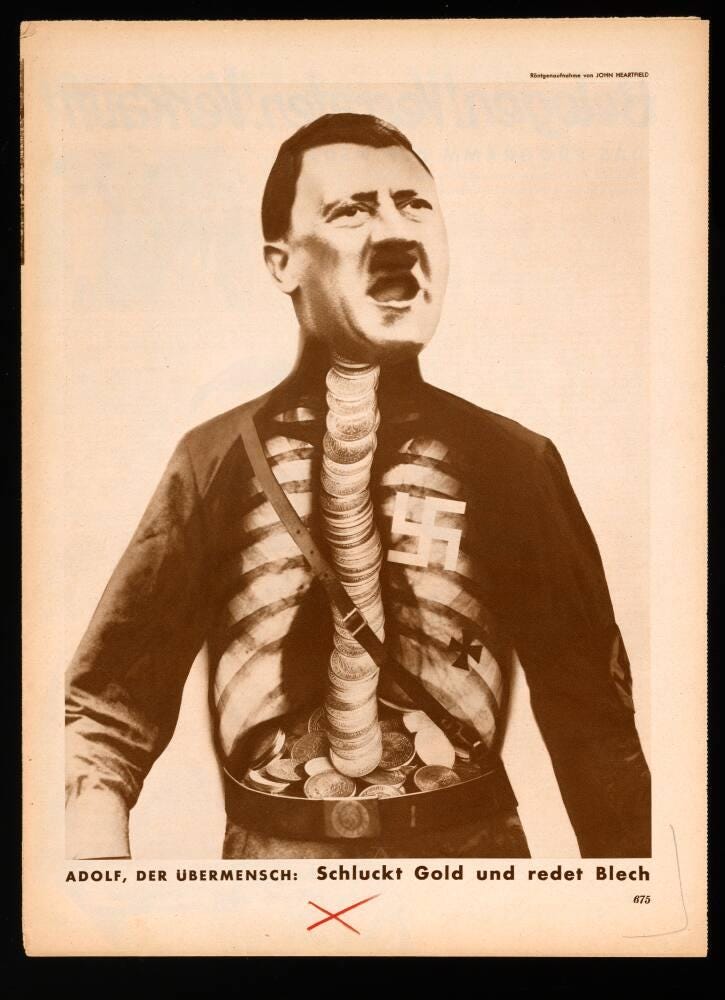

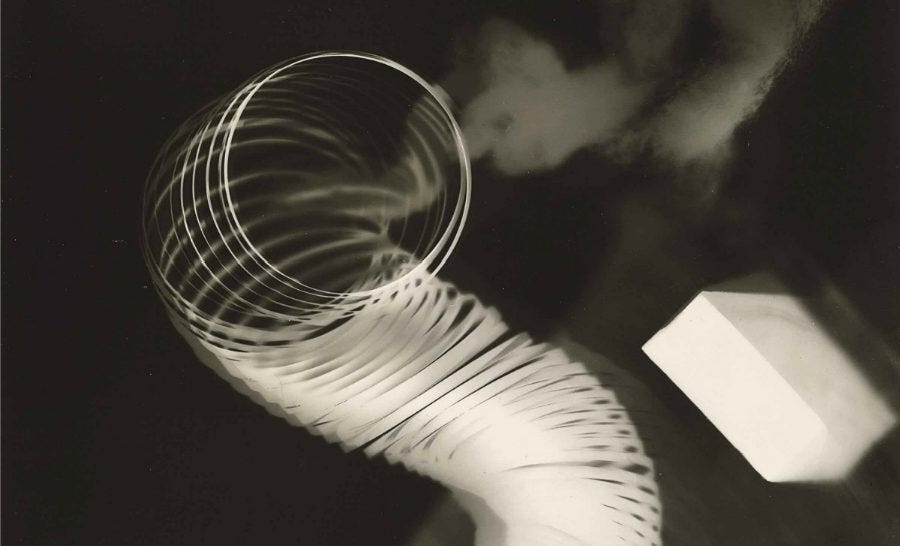

While Zurich provided Dada’s inception, Berlin quickly became its most politically charged laboratory. There, Hannah Höch’s radical photomontages, most notably Cut with the Kitchen Knife (1919), braided magazine fragments into searing critiques of Weimar politics and rigid gender norms (Höch). Elsewhere, Jean Arp embraced chance by dropping torn papers onto canvases and affixing them where they fell, yielding organic abstractions that mocked intentional composition (Arp). Excluded from Berlin’s scene, Kurt Schwitters devised his own “Merz” collages from everyday detritus, train tickets, packaging, and wood shards, transforming refuse into dynamic assemblages that satirized consumer excess (Schwitters). Simultaneously, John Heartfield wielded photomontage as a weapon against Nazi propaganda, as in Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Tin (1932), demonstrating Dada’s potency for direct political engagement (Heartfield). Across the Atlantic, Man Ray’s cameraless “rayographs” extended these ideas into photography, producing shadowlike abstractions that further blurred distinctions between art and accident (MoMA).

By the early 1920s, Dada’s anarchic fervor in Paris had coalesced into a more constructive project. André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) proclaimed a “super‑reality” wherein the unconscious mind, liberated from rational restraints, could revolutionize human experience (Breton 3). Drawing on Freudian psychoanalysis, particularly his essay The Uncanny (1919), Surrealists pursued automatism in writing and art, seeking to “express…. the actual functioning of thought” unmediated by reason (Breton 5; Harris and Zucker). With the founding of the Bureau of Surrealist Research in Paris, poets like Philippe Soupault and Louis Aragon joined painters such as André Masson and Yves Tanguy in experiments that laid the groundwork for automatic drawing and collage (Wikipedia).

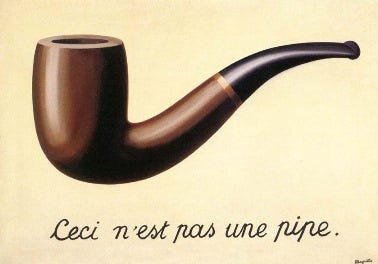

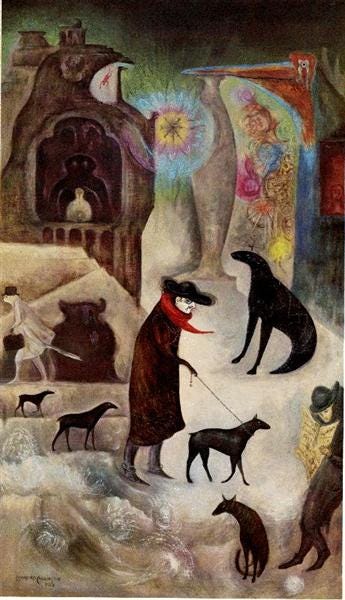

Surrealism inherited Dada’s love of juxtaposition and surprise, but repurposed it to unlock psychic depths rather than provoke scandal. Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931) maps dream‑time via deformed clocks draped across barren landscapes, realized through his “paranoiac‑critical method” of self‑induced hallucination (Encyclopedia Britannica; Talbot). René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1929) subverts semiotics by declaring “Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” reminding viewers that representation and reality remain irreducibly separate (Encyclopedia Britannica). Max Ernst’s Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924) fuses oil and collage to evoke a primal nightmare, while Joan Miró’s Harlequin’s Carnival (1924–25) arranges biomorphic forms into a riot of subconscious play (MoMA; Tate). Meret Oppenheim’s Object (1936), a teacup clad in fur, upends domestic banality with erotic disquiet (Fundación Juan March). In literature and film, Breton’s novel Nadja (1928) and Buñuel and Dalí’s Un Chien andalou (1929) further blurred real and surreal realms, inaugurating a multimedia revolution.

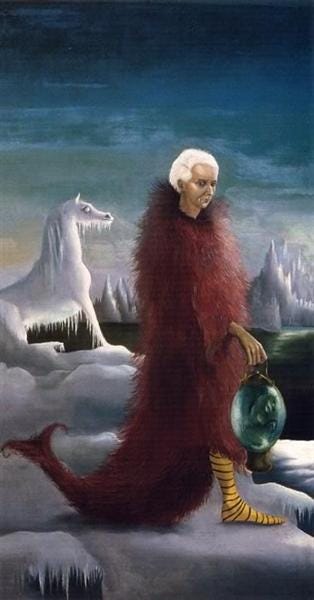

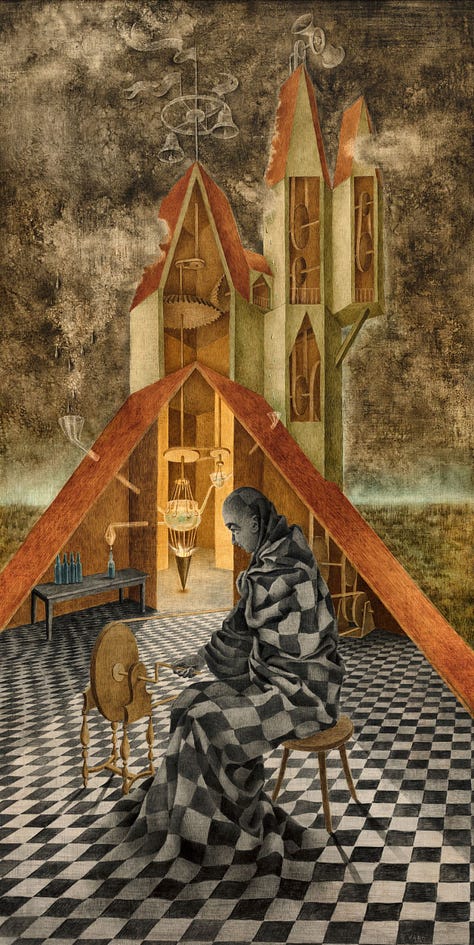

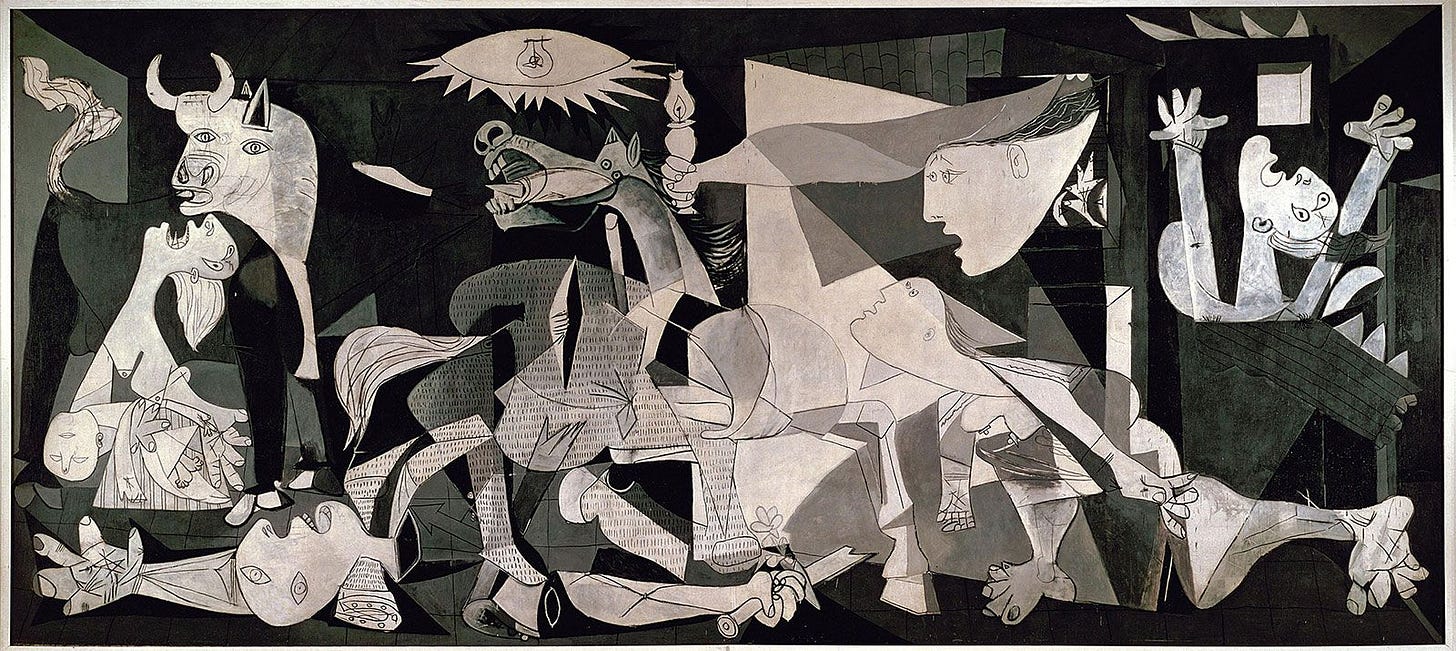

Surrealism’s international reach accelerated throughout the 1930s. In New York, the Arensbergs’ salons showcased Dalí, Picabia, and Man Ray, culminating in the 1937 MoMA exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (MoMA). Mexico City’s 1940 show at Galería de Arte Mexicano introduced Latin American audiences to European Surrealism, while exiled artists Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo melded Surrealist techniques with indigenous mythologies (Vogue). Frida Kahlo’s The Two Fridas (1939), though intensely personal, paralleled Surrealist doubling and symbolism alike (Smith). Wifredo Lam’s The Jungle (1942–43) fused Afro‑Caribbean imagery with Surrealist distortion to critique colonial exploitation, cementing Latin America’s vital contribution to the movement (MoMA). Politically, Surrealists often aligned with anti‑fascist causes, Breton briefly joined the French Communist Party in 1927, and Picasso’s Guernica (1937) resonated with Surrealist anti‑war sentiment (LibCom).

Although formal Dada and Surrealist groups dissolved by mid‑century, their legacies endure. Fluxus artists revived Dada’s event scores and readymades in the 1960s (“Fluxus”), while Conceptual artists from the 1960s onward championed idea over object (“Conceptual Art”). Situationists adopted détournement, hijacking mass media to expose ideological manipulation (Tate). Recent retrospectives, Tate Modern’s Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Paris, New York (2005) and MoMA’s Dada (2006), alongside twenty‑first‑century Surrealism exhibitions at Centre Pompidou and Tate Modern, reaffirm the movements’ ongoing capacity to question complacency and reimagine reality (“Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Paris, New York”; Tate; “Surrealism Beyond Borders”).

From Cabaret Voltaire’s absurdist provocations to Breton’s psychic expeditions, Dada and Surrealism represent twin revolutions in modern art. By exalting chance, nonsense, and the unconscious, these movements dismantled inherited hierarchies of taste and authority, forging new artistic paradigms that persist in contemporary practices of appropriation, institutional critique, and political engagement. In an age still grappling with the legacies of rationalism and conformity, the anti‑art gestures first unleashed by Dada and refined by Surrealism continue to challenge us to see, and imagine, the world anew.

References:

Arp, Jean. Collage with Squares Arranged According to the Laws of Chance. 1916. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/Jean-Arp.

Ball, Hugo. Dada Manifesto. 14 July 1916. Wired, www.wired.com/beyond-the-beyond/2016/07/hugo-balls-dada-manifesto-july-2016.

Cabaret Voltaire. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/art/cabaret.

Breton, André. Manifesto of Surrealism. 1924. University of Hawai‘i, www2.hawaii.edu/~freeman/courses/phil330/MANIFESTO%20OF%20SURREALISM.pdf.

Conceptual Art. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/art/conceptual-art.

Duchamp, Marcel. Fountain. 1917. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/topic/Fountain-by-Duchamp.

Dada. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/art/Dada.

Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Paris, New York. Tate Modern, www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/dada.

Fluxus. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fluxus.

Heartfield, John. Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Tin. 1932. TheArtStory, www.theartstory.org/artist/heartfield-john/.

Harris, Beth, and Steven Zucker. Surrealism and Psychoanalysis. Smarthistory, smarthistory.org/surrealism-and-psychoanalysis/.

Höch, Hannah. Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer‑Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany. 1919. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/topic/Cut-with-the-Kitchen-Knife.

MoMA. Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2823.

MoMA. Max Ernst: Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale. www.moma.org/collection/works/79293.

MoMA. What Is a Rayograph? www.moma.org.

Picabia, Francis. Francis Picabia. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/Francis-Picabia.

Schwitters, Kurt. Kurt Schwitters. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/Kurt-Schwitters.

Smith, Patricia. Frida Kahlo’s The Two Fridas. Journal of Modern Art, vol. 12, no. 3, 2010, pp. 45–62.

Talbot, Margaret. Dalí’s Nightmares. The New Yorker, 18 Feb. 2002.

Tzara, Tristan. Dada Manifesto 1918. University of Pennsylvania, writing.upenn.edu/library/Tzara_Dada-Manifesto_1918.pdf.

Wikipedia contributors. Surrealism. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surrealism.

Surrealism Beyond Borders. Tate Modern, www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/surrealism-beyond-borders.

Vogue. Women of Surrealism: Carrington, Varo, and Kahlo. 15 Oct. 2021, www.vogue.com/article/women-of-surrealism.

So good. Something in this to satisfy one of Surrealism for the day, and want go drink more tomorrow. Like Alice, I always wonder if it will decide to: Make me smaller today or Larger tomorrow. It has that power—Like the mushroom we might nibble just enough of.

Frida Kahlo said she was not surrealist, that she just painted her reality. Well, pain and doppelgänger ar overreal, surreal. And Guernica, the cubist dismemberment of a black and white picture of war from the newspapers...

What I love is how you include woe as a surreal experience.

Loving this article. :)