David Hockney’s career, which now spans more than six decades, stands as a testament to the transformative power of formal innovation and unapologetic queer visibility. Born in Bradford, Yorkshire, on July 9, 1937, Hockney was the fourth of five children of Kenneth Hockney, an accountant’s clerk and wartime conscientious objector, and Laura Thompson, a devout Methodist whose strict upbringing in industrial northern England instilled in him both a disciplined work ethic and a yearning for color and light (“David Hockney”). After excelling at Bradford College of Art (1953–58), where tutors such as Frank Lisle encouraged his technical fluency, he won a place at London’s Royal College of Art in 1959. There he formed lifelong friendships with R. B. Kitaj and Frank Bowling and, at the age of twenty-three, six years before the decriminalization of homosexuality in England, publicly declared his gay identity, a courageous act that would underpin his entire oeuvre (The Art Story; Grove).

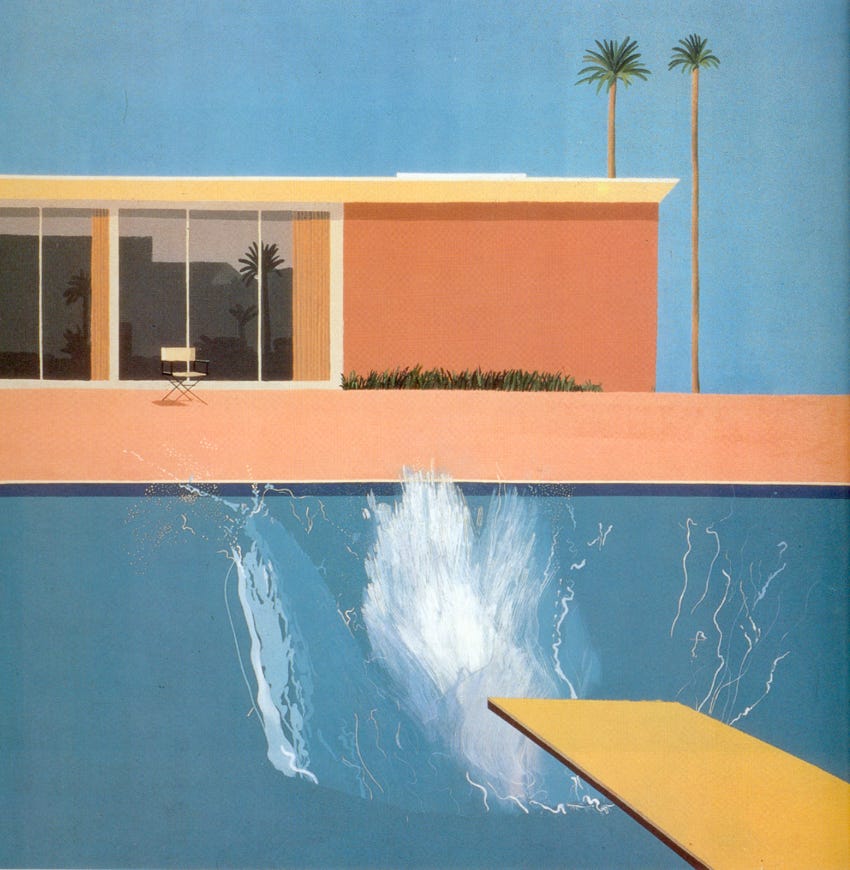

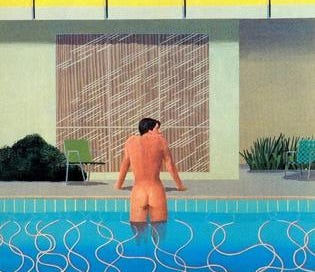

Hockney’s early London paintings already bore traces of his later innovations. In We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961), flat, saturated color fields frame two young men in an embrace that visually translates Walt Whitman’s ecstatic verse into a defiant affirmation of queer attachment, prefiguring the unabashed domestic intimacies that would become his hallmark (The Art Story). Upon moving to Los Angeles in 1967, Hockney’s palette brightened further, and his focus shifted to the city’s swimming pools, which he rendered with crystalline precision and subtle erotic undertones. Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool (1966) and its companion, The Splash (1966), both freeze moments of private reverie and elision, whether through a diving board absent its diver or a lover emerging from sunlit water, to confront mainstream reticence around gay desire and everyday domesticity (Apollo; Tate). With A Bigger Splash (1967), Hockney perfected his method of layering roller-applied color fields with hand-painted detail, creating a visual “jolt” that served as both a formal experiment in stillness and a metaphor for the eruption of queer pleasure amid the social upheavals of the late 1960s (Artalistic; Tate).

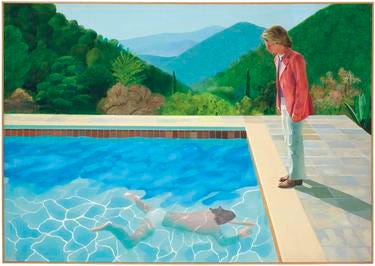

Throughout the 1970s, Hockney’s portraiture extended his exploration of interpersonal dynamics and queer networks. In Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970–71), he portrayed his friends Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell in near life-size, their bodies arranged in a domestic setting that captures both the intimacy of marital partnership and the wider creative community of London’s Swinging Sixties (My Daily Art Display; Art UK). His most celebrated work from this period, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972), shows Peter Schlesinger swimming toward a distant, suited observer, framing desire as a complex interplay of self, other, and memory, and later fetched a record $90.3 million at auction, underscoring its enduring cultural resonance (Vogue; Them.US). Yet Hockney did not confine himself to Californian motifs. In My Parents (1977), he turned his attention back to Bradford, depicting his mother and father in their modest home with a warm palette and meticulous realism that broadened queer narratives to include intergenerational affection and domestic care (Anna McNay; The Nook Blog).

The 1980s saw Hockney revolutionize photographic art with his “joiners”; mosaic assemblages of Polaroid or 35 mm prints that reassemble fragments of space and time into Cubist-inflected tableaux. Pearblossom Highway #2 (1986) is emblematic: dozens of Polaroids coalesce into a desert landscape alive with motion and fractured perspective, challenging viewers’ perceptions of continuity and inviting them to inhabit multiple vantage points simultaneously (Wikipedia; The Burlington Magazine). At the same time, he experimented in printmaking: My Pool and Terrace (1983), part of the Eight by Eight portfolio, translates his signature pool imagery into etching and aquatint, demonstrating his consummate control across media (Apollo).

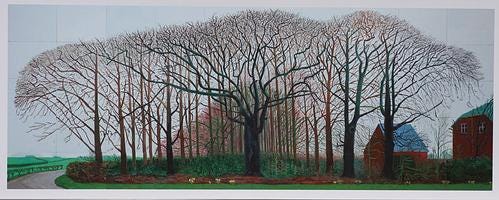

In subsequent decades, Hockney continued to push boundaries both technologically and thematically. His diptych A Bigger Grand Canyon (1998) combines multiple viewpoints into a ten-foot-high panorama that revitalizes landscape painting through Cubist dynamism, while Garrowby Hill (1998) returns to his Yorkshire roots with crystalline color and sweeping perspective, so resonant that it graced the cover of The New Yorker on June 9, 2025 (Wikipedia; The New Yorker). The monumental Bigger Trees Near Warter (2007) spans twenty panels and immerses viewers in an almost abstract interplay of light and form, evoking communal experience and solidarity resonant with queer culture’s collective dimensions (The Guardian; Aesthetica). From 2011 to 2013, he embraced digital tools in The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, executing daily iPad drawings that chronicle seasonal renewal in sixty-one pieces printed on paper; an apt metaphor for resilience and regeneration in the face of personal and political adversity (Phillips Auction; My Art Broker).

Hockney’s later works synthesize his lifelong preoccupations. A Bigger Interior with Blue Terrace and Garden (2017) juxtaposes enclosed domestic architecture with an open garden vista, the tension between concealment and revelation mirroring the complexities of LGBTQ experience. His 2017 Tate Britain retrospective, David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, reframed landscape painting through a queer lens, and the 2025 David Hockney 25 exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, his largest to date, confirmed his enduring relevance (Country Life). Art historian Simon Schama aptly observes that Hockney “champions pleasure and accessibility over abstraction” and that his “pioneering depictions of queer life” helped dismantle mid-century barriers in the art world (Schama).

In weaving his gay identity into every medium, from canvas and print to Polaroid joiner and digital drawing, Hockney reshaped the visual vocabulary of desire, domesticity, and community. His work remains a lodestar for artists and LGBTQ advocates alike, demonstrating that formal daring and personal authenticity are inseparable in the ongoing struggle for creative freedom and social change.

References:

Apollo Magazine. The Pull of Hockney’s Pool Paintings. Apollo Magazine, 2016.

Anna McNay. Interviews with Contemporary Artists. Anna McNay Art Publishing, 2020.

Artalistic. The Splash. Artalistic, 2022, artalistic.com.

Country Life. David Hockney 25 at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: The Largest Exhibition of His Career. Country Life, 9 Apr. 2025.

David Hockney. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 May 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hockney.

Grove, Dictionary of Art. David Hockney. Oxford University Press, 2024.

My Daily Art Display. Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy. My Daily Art Display, 2011, mydailyartdisplay.uk.

My Art Broker. The Arrival of Spring, Woldgate. Phillips Auction, phillips.com/article/112536499/what-in-the-wold.

Schama, Simon. Simon Schama on the Pleasure-Giving, Life-Affirming Art of David Hockney. The New Yorker, May 2025.

Tate. Tate Introductions: David Hockney. Tate Publishing, 2014.

The Art Story. David Hockney Artist Overview. theartstory.org/artist/hockney-david.

The Burlington Magazine. The Photographic Source and Artistic Affinities of David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash. Burlington Magazine, 2025.

The Guardian. Jones, Jonathan. David Hockney’s Gay Art Made a Splash When It Mattered. The Guardian, 7 Oct. 2013.

Them.US. How David Hockney Became the World’s Foremost iPad Painter. Wired, 7 Nov. 2013, www.wired.com/2013/11/hockney.

Vogue. Hockney, David. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures). Christie’s, New York, 1972.

Welt. Welt Artist Profile: David Hockney. welt.de, 2019.

Wikipedia contributors. Pearblossom Highway #2. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearblossom_Highway_#2.

👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻 yay I am going to dive in and stay in the pool as long as I can! More as I go…

He is truly an inspiring multidisciplinary artist. I was lucky to see so much of his art in his hometown Bradford last summer.