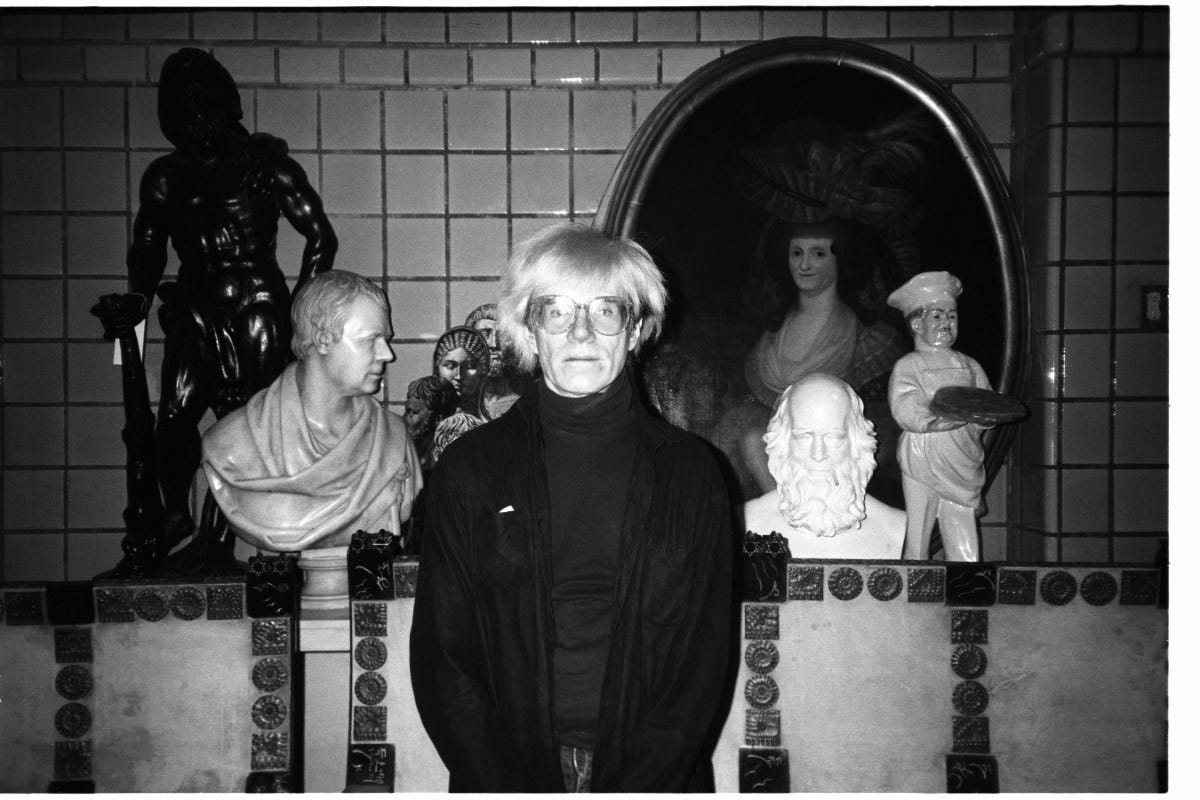

Andy Warhol (1928–1987) occupies a singular position in twentieth-century art as the preeminent figure of the Pop Art movement, whose exploration of consumer culture, mass media, and celebrity reshaped the boundaries of high and low art. Born Andrew Warhola in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Slovakian immigrant parents, Warhol’s early exposure to Byzantine Catholic iconography and his prolonged childhood illness fostered a fascination with images of suffering and sanctity that would resurface throughout his career. Although he adopted a public persona of detachment and irony, Warhol was a gay man whose sexuality informed both his subject matter and his social networks, even if he himself rarely addressed it publicly.

Andrew Warhola was born on August 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the eldest of three children of Slovak immigrants Ondřej (Andrew) and Julia (Zavacká) Warhola. From age eight, Warhol endured bouts of Pseudomembranous Epiglottitis, which often confined him to bed for weeks at a time (The Biography of Andy Warhol). During these periods, he delved into magazines, comic books, and storytelling, developing a precocious ability for drawing and narrative that would underpin his later work. His mother, Julia, nurtured his talent by taking him regularly to the Carnegie Museum of Art, where he encountered Byzantine iconography and the grand traditions of European painting; experiences that left an indelible mark on his aesthetic sensibility (The Biography of Andy Warhol).

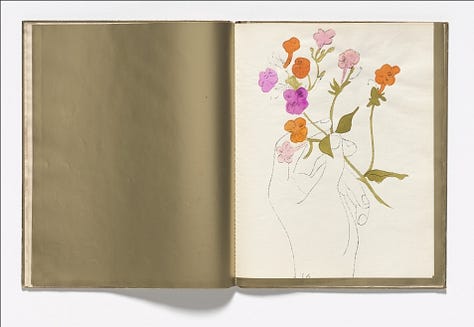

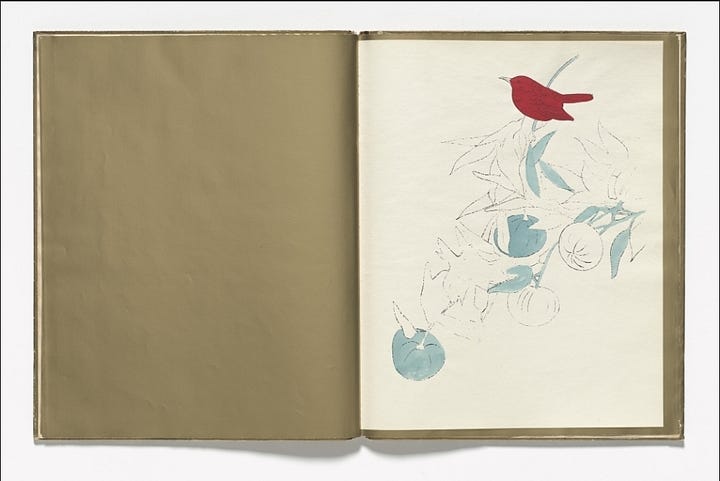

In 1945, Warhol enrolled at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), studying pictorial design under instructors such as Philip H. Dike. He graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1949 (Biography of Andy Warhol). His senior project, a marionette design incorporating imagery drawn from comics, already demonstrated his predilection for merging popular culture with traditional techniques. That same year, Warhol moved to New York City and began his career as a commercial illustrator, developing the blotted-line technique, which involved tracing ink drawings onto watercolor paper, then transferring them via xerographic methods to achieve crisp lines and vibrant patterns (Warhol and Hackett, POPism 12).

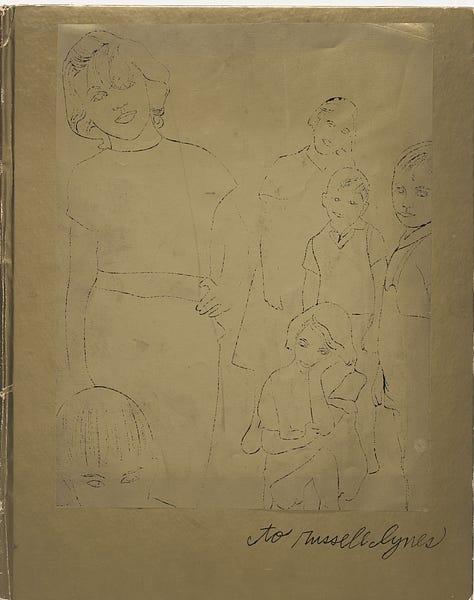

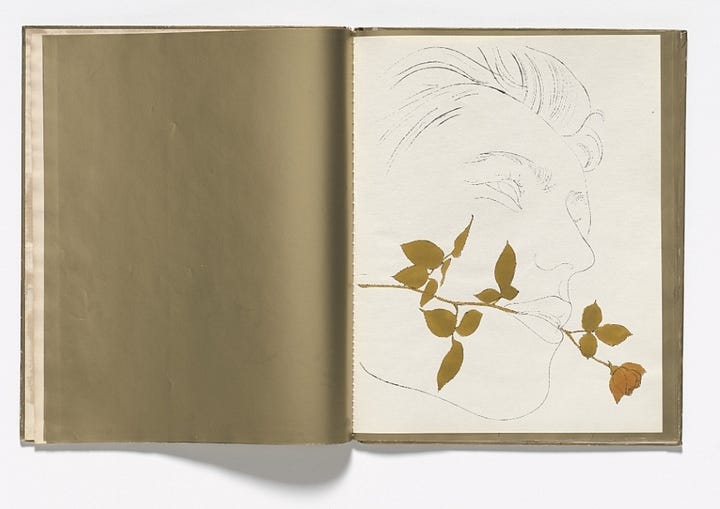

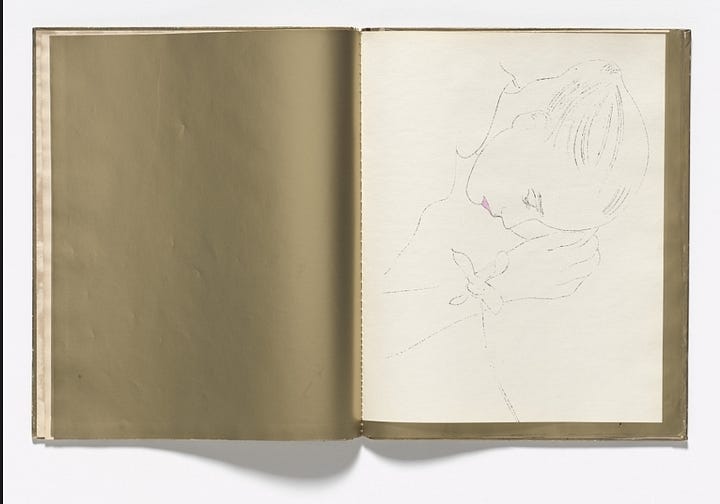

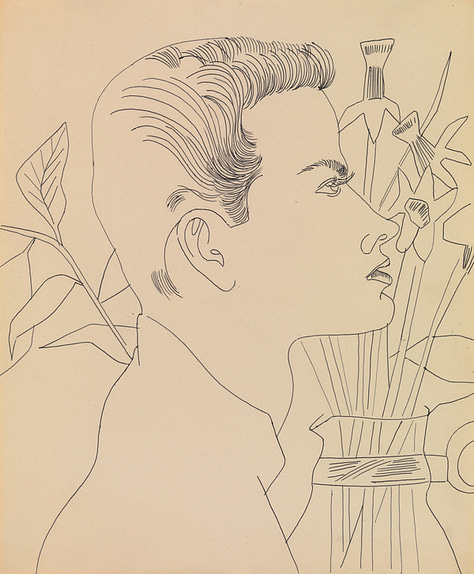

Underlying the commercial veneer of his early work lay a discreet but persistent queer sensibility. As art historians Trevor Fairbrother and Nina Schleif note, Warhol’s collaborations with photographer Edward Wallowitch (1924–2016) produced images of lithe young men that Warhol transposed into his own eroticized illustrations (Becoming Queer: Warhol in the 1950s). In producing the 1957 collection A Gold Book, Warhol printed pastel-and-ink drawings of semi-nude and nude male figures juxtaposed with Wallowitch’s photographs, openly engaging homoerotic imagery at a moment when homosexuality was still criminalized (Boy Book Drawings; “A Gold Book”). These early forays into gay representation, though small in scale, laid the groundwork for Warhol’s lifelong visual preoccupation with the male body and performance of gender.

Warhol’s transition from commercial illustrator to avant-garde artist was cemented with his November 1962 exhibition at the Stable Gallery, where he presented thirty-two canvases of Campbell’s Soup Cans. By appropriating the ubiquitous soup can and replicating it through silkscreen, Warhol challenged the art world’s entrenched hierarchies and launched Pop Art as a dominant cultural force (Warhol and Hackett, POPism 45; Gopnik 102). Although these canvases did not explicitly foreground queer content, they embodied a subversive ethos akin to gay underground practices, which also repurposed mass-circulation imagery, such as photo-booth strips and fanzines, to create alternative social spaces (Gopnik 103–05; “Andy Warhol’s Queer Practice”).

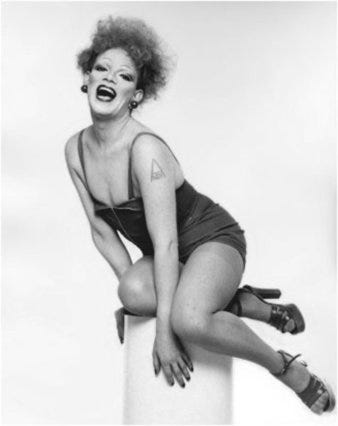

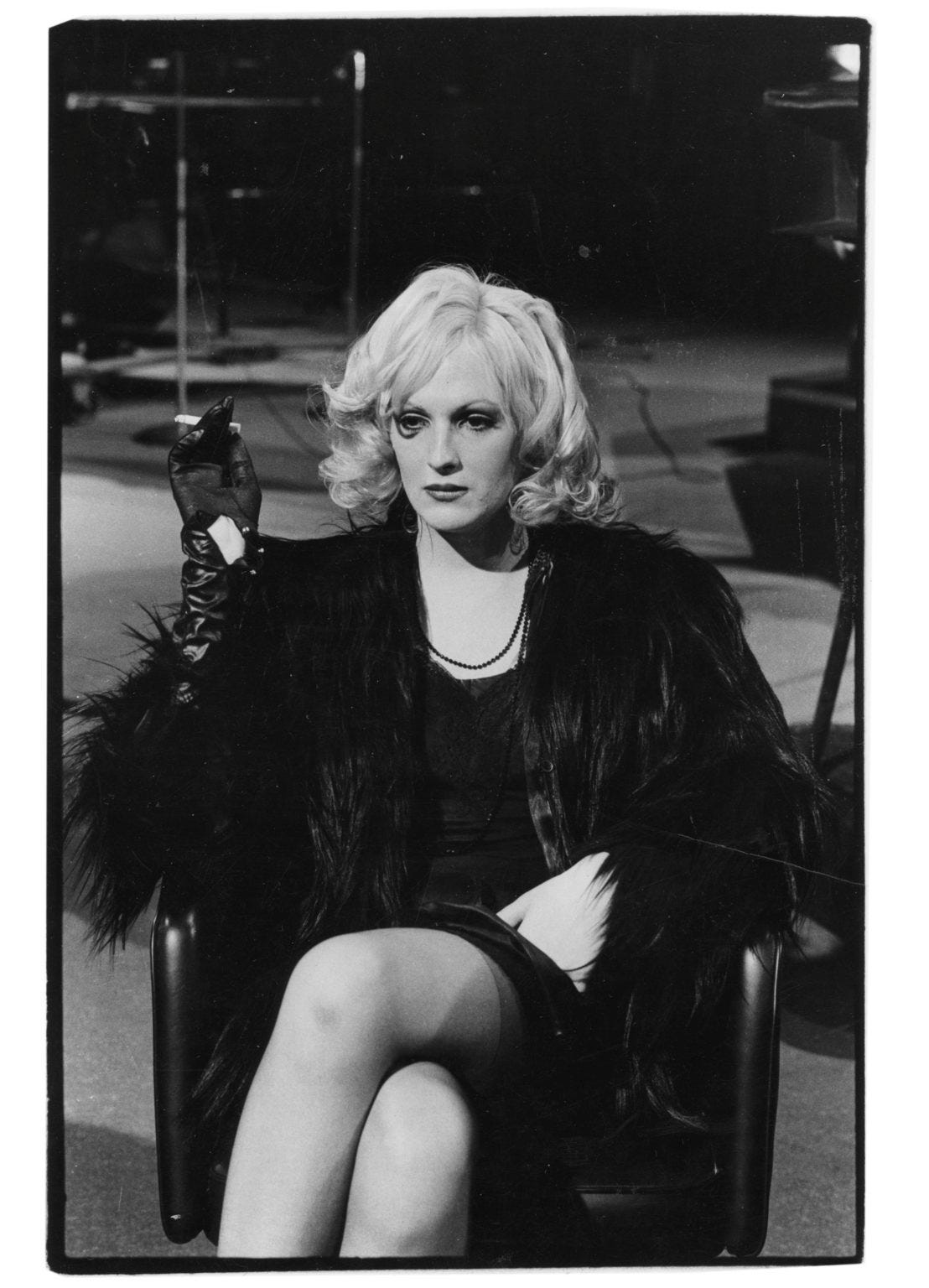

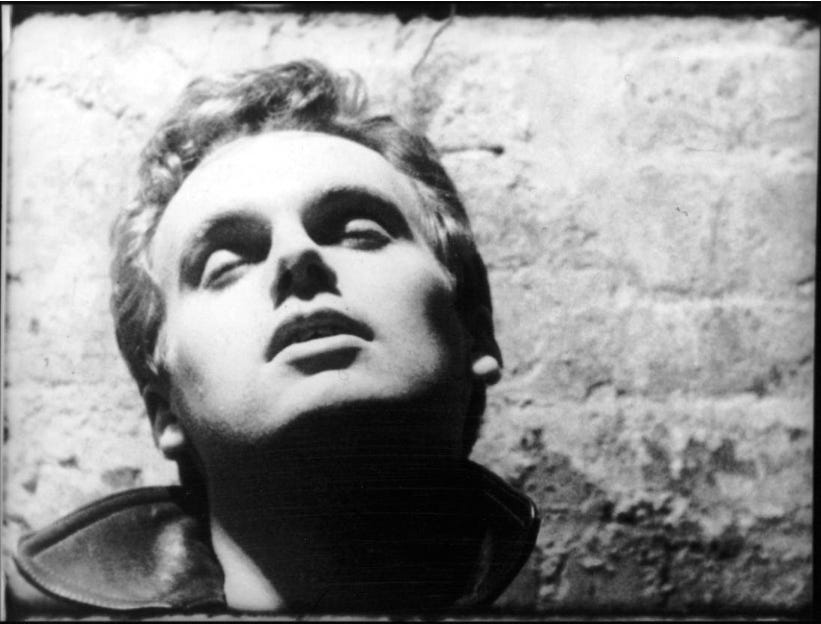

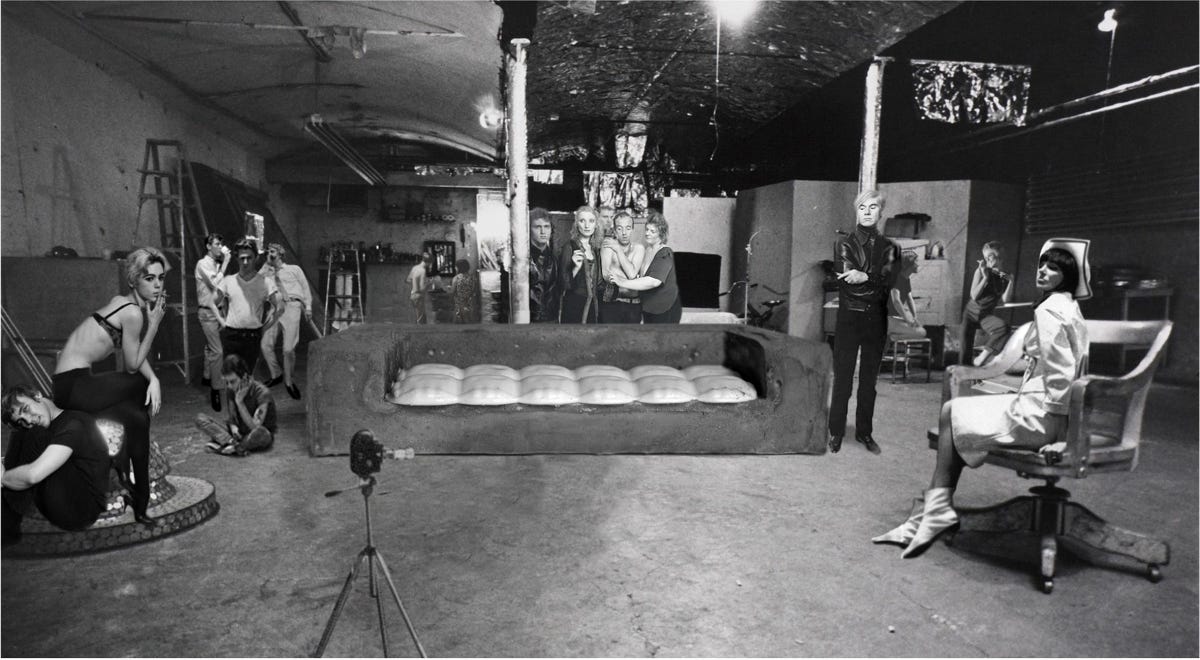

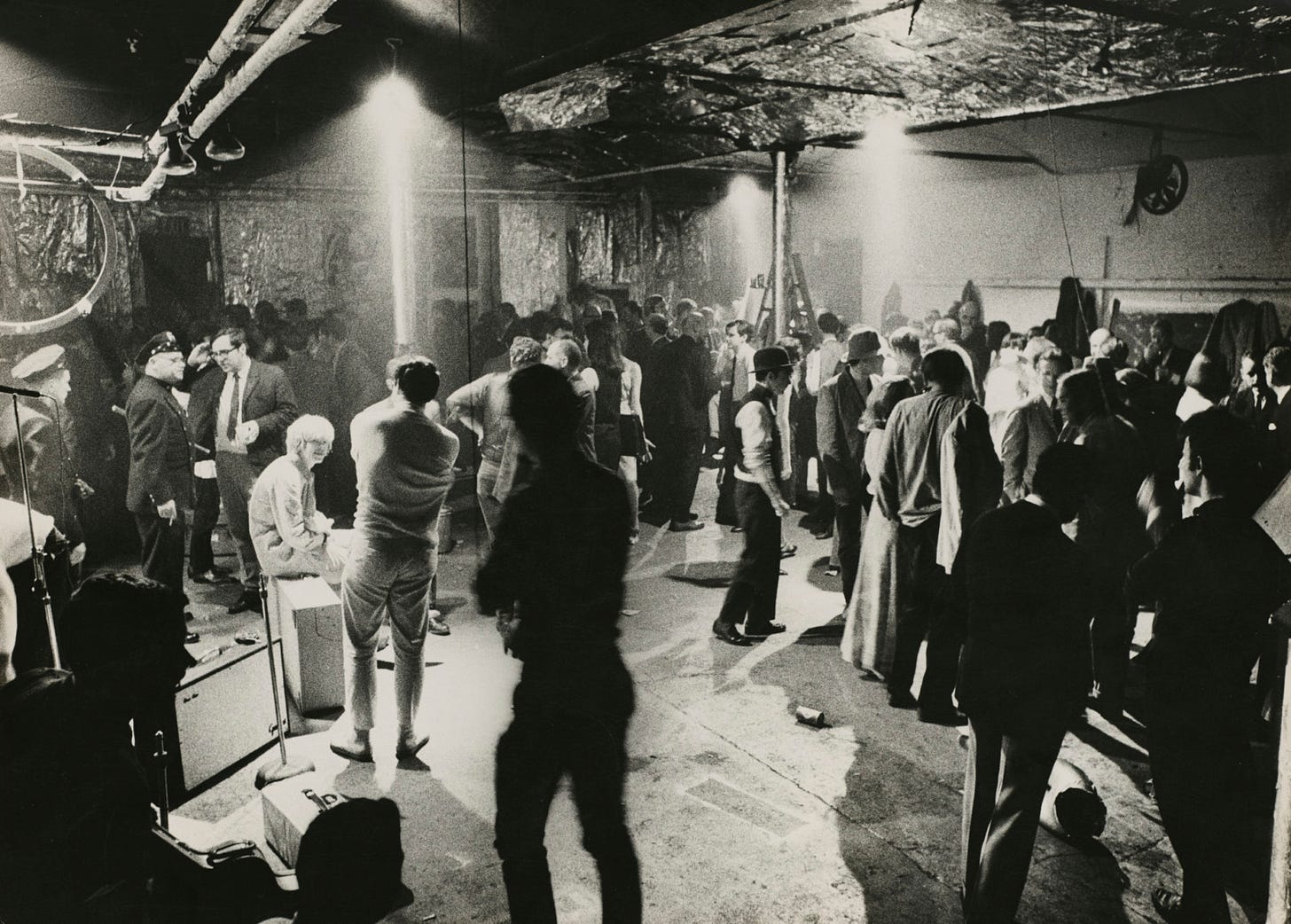

By 1964, Warhol had established “The Factory” on East 47th Street, transforming a decaying industrial loft into an epicenter of multimedia production. The Factory served not only as a studio for painting and silkscreen but also as a laboratory for experimental filmmaking, music, and performance. Factory denizens included gay sculptor and actor Ondine (Brian Cook), bisexual singer Nico, transgender performer Jackie Curtis, and drag icons Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn (“Warhol superstars”; Them.us Editors). Through Screen Tests, short, silent 16 mm film portraits, Warhol captured the unvarnished performativity of gender, often featuring queer sitters striking poses that blurred normative expectations (“Girl Interrupted: The Queer Time of Warhol’s Cinema”). As Blake Gopnik has argued, Warhol’s films and photography manifested a “queer practice” that resisted commodification by privileging experimentation and communal authorship (Warhol’s Defiant Hopes for Queer Art; “Andy Warhol's Queer Practice”). These gatherings, magnified by events like the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, which paired The Velvet Underground’s music with Warhol’s film projections, solidified The Factory as a refuge for queer youth within a broader culture still hostile to homosexuality (Colacello 217).

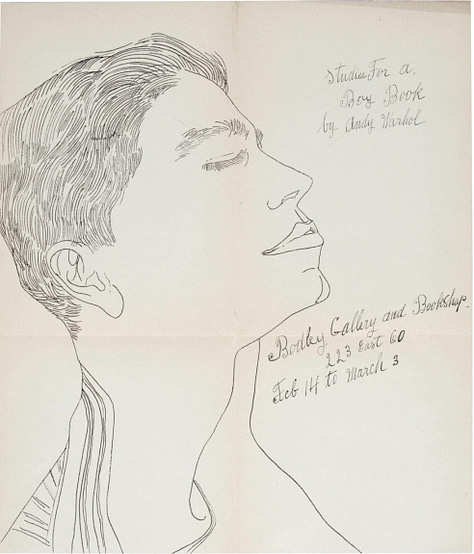

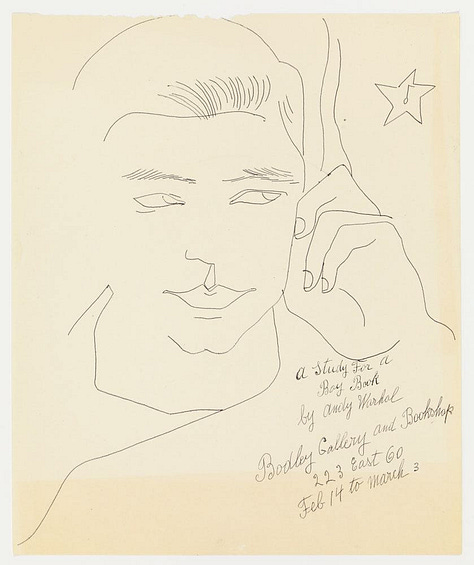

Among Warhol’s earliest explicit celebrations of gay desire are the Boy Book drawings, produced between approximately 1955 and 1962. These pencil, ink, and pastel sketches depict youthful, often nude or partially clothed males in poses evocative of gymnastic or bathing scenes, charged with an intimate gaze that diverged sharply from the objectifying male nude tradition (Warhol Museum; Hyperallergic). In February 1956, Warhol exhibited a selection of these drawings under the title “Studies for a Boy Book” at the Bodley Gallery, pioneering the display of openly homoerotic imagery in New York’s commercial gallery system (Boy Book Drawings; Warholstars.org). The tender, sometimes flirtatious gestures, roses held between lips, butterflies fluttering around bodies, imbue these works with camp sensibilities that prefigure his later Pop aesthetics (“Pop Out: Queer Warhol”).

Shortly after Marilyn Monroe’s untimely death in August 1962, Warhol created the Marilyn Diptych, featuring fifty silkscreened images of Monroe’s face, half in vivid color, half in stark black-and-white, spanning two large panels (Gopnik 104; The Biography of Andy Warhol). While widely interpreted as a meditation on celebrity, commodification, and mortality, the diptych also resonates with queer readings of identity and performativity. Monroe’s crafted public persona, alternately blonde bombshell and vulnerable ingénue, mirrored the constructed identities of queer individuals navigating a heteronormative culture (Gopnik 105; “Do you think Pop Art's queer?”). Warhol’s repetitive printing flattens her image into an icon, symbolizing how both female and queer bodies were subjected to mass consumption and spectacle. The fading, ghostly grayscale half of the diptych suggests the erasure of identity under commodification, a process familiar to gay men whose identities were marginalized by mainstream society.

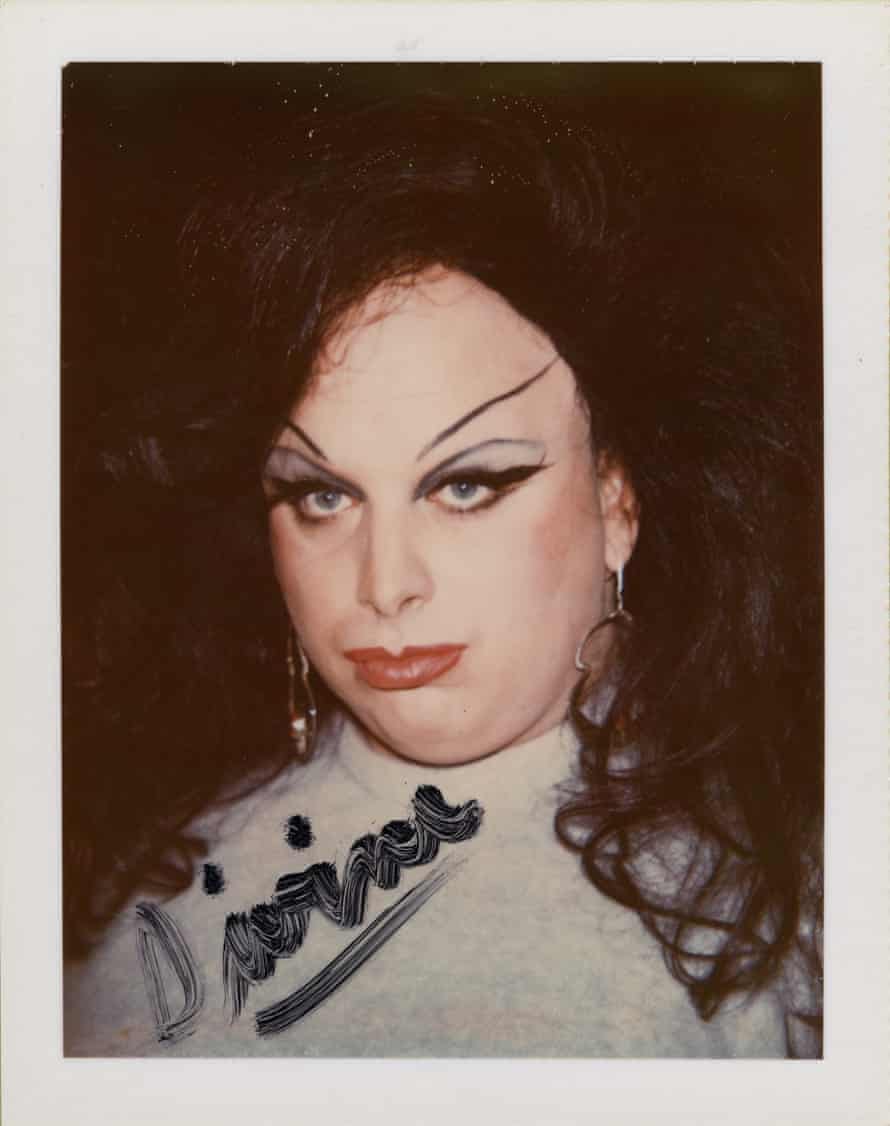

From 1970 until his death, Warhol published and edited Interview magazine, dedicated to celebrity interviews, fashion, and nightlife. The magazine became a platform for queer visibility, featuring covers that celebrated LGBTQ figures, especially drag performers and disco-era luminaries. Notable among these are Warhol’s silkscreen portraits of Divine (Harris Glenn Milstead), which depict the drag icon’s exaggerated makeup and clothing in Day-Glo hues, elevating camp aesthetics to high art (Warhol Museum; Hyperallergic). Similarly, Warhol’s depictions of Candy Darling, captured in both Polaroid snapshots and large-scale silkscreens, canonized a transgender subject at a moment when trans representation was scarce in the fine art realm (Them.us Editors). These works, produced in the mid-1970s, affirmed Warhol’s ongoing engagement with gender nonconformity and reflected his belief that celebrity could be a vehicle for legitimizing marginalized identities (“Pop Out: Queer Warhol”; “Andy Warhol's Queer Practice”).

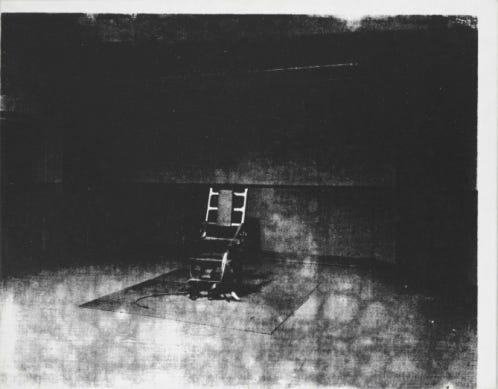

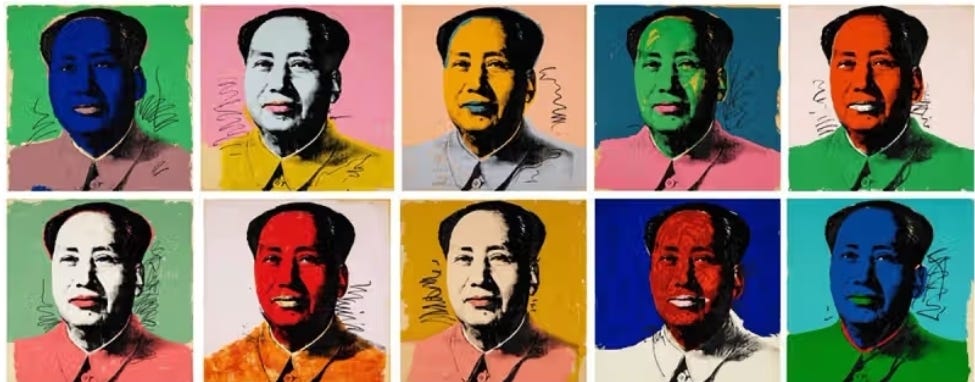

Parallel to his portraits of celebrities, Warhol explored themes of death, power, and spectacle in series such as Electric Chair (1963–64) and his portraits of Chairman Mao (1972–73). Though not explicitly queer in subject, these works resonate with Warhol’s broader concern with violence and marginalization; concerns also central to queer experiences in midcentury America. The Electric Chair canvases, silkscreened in lurid colors against stark backgrounds, evoke the tension between public execution as spectacle and individual human suffering, analogous to the persecution faced by gay men under criminalization (Warhol Foundation; Gopnik 107). In his Mao portraits, Warhol deployed the same silkscreen method to transform an authoritarian figure into a pop icon, underscoring the paradox of power and its reproduction; an irony that parallels how queer identities were both vilified and fetishized by mainstream culture (“Andy Warhol’s Queer Practice”).

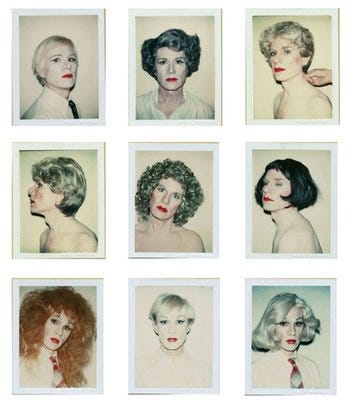

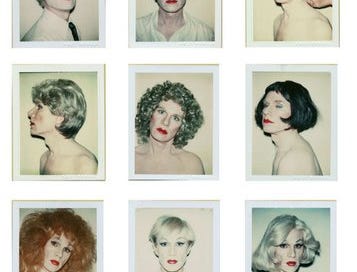

Warhol’s self-portrait practice, from early black-and-white photographs to colorized Polaroids and silkscreens, often employed masks or obfuscations that underscore identity’s constructed nature. In his 1975 Self-Portrait in Drag series, Warhol dressed in full drag regalia, wig, makeup, and sequined gown, and photographed himself, challenging both his own public persona and normative gender expectations (Warhol Museum; “Do you think Pop Art's queer?”). Concurrently, his experimental films, such as Kiss (1963), which documents couples kissing for extended periods, and Blow Job (1964), a shorts silent film focusing on a man purportedly receiving oral sex, pushed the boundaries of acceptable representation of queer sexuality on screen (Hyperallergic; “Girl Interrupted: The Queer Time of Warhol’s Cinema”). These films, often dismissed by early critics as mere “screen tests,” are now acknowledged as pioneering queer cinema that centered bodily pleasure and eroticism without moralizing overt commentary (“Andy Warhol's Defiant Hopes for Queer Art”).

“The Factory”, initially located at 231 East 47th Street and later moved to 33 Union Square West, was as much a social nexus as it was an art studio. Here, Warhol extended an open-door policy to artists, drag performers, gay and trans men, and straight collaborators, fostering a fluid exchange of ideas across media. Candy Darling recalled how drag queens and gay men “sat on crates, smoking, talking, drinking champagne,” seamlessly integrated into artistic collaborations rather than relegated to the margins (Them.us Editors). The Factory’s inhabitants, Johnny Dodd, Jackie Curtis, Ultra Violet (Isabelle Collin Dufresne), and Eric Emerson, often appeared in Warhol’s films, contributing to an ethos of collective authorship and performance of identity (Colacello 217; Warholstars.org). These gatherings culminated in the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966–67), a series of multimedia events that combined live rock music (The Velvet Underground), stroboscopic light shows, and Warhol’s film projections, further situating queer creativity at the vanguard of countercultural expression (Colacello 218; “Girl Interrupted: The Queer Time of Warhol’s Cinema”).

While Warhol maintained a veil of inscrutability in public, his private life was marked by significant queer partnerships. From 1968 to 1980, he was involved with Jed Johnson, a furniture designer and Factory assistant; Johnson’s devoted care after Warhol’s near-fatal shooting by Valerie Solanas in June 1968 solidified their bond, though Warhol publicly referred to Johnson only in coded language within his diaries (Warhol and Hackett, The Andy Warhol Diaries 243; Colacello 312). In the early 1970s, Warhol also had a relationship with Jon Gould, a straight ex–Vogue editor and junior partner at Christie’s, who introduced him to Wall Street circles. Although Warhol rarely acknowledged these relationships in interviews, friends like Pat Hackett, his diary transcriber, recall Warhol describing Johnson as “my boyfriend” when no one else was around (Warhol and Hackett, The Andy Warhol Diaries 250; Biography of Andy Warhol). Warhol’s private diaries further reveal his anxieties during the early AIDS crisis: in December 1984, he wrote, “The New York Times says you can’t get gay cancer from casual contact, but I’m still not sure. I’m terrified someone will sneeze on me” (Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDS). These entries underscore the collision of faith, fear, and desire in Warhol’s later years, reflecting how his queer identity was shaped by broader social crises. (The Andy Warhol Museum, Oxford Academic, Wikipedia)

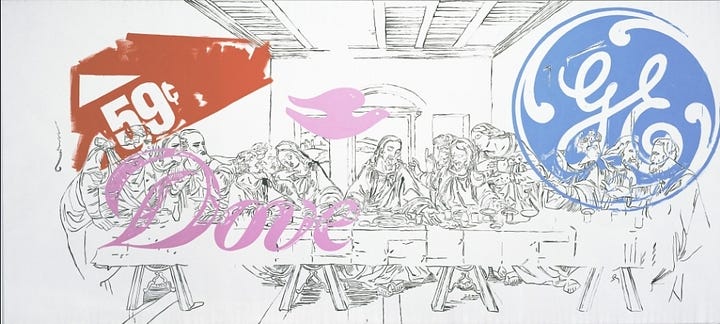

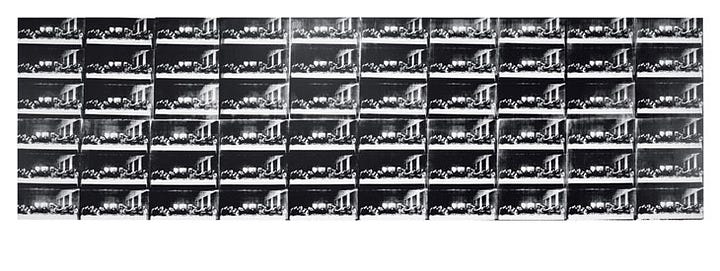

Raised in the Byzantine Catholic tradition, Warhol’s late-career art frequently engaged religious imagery as a means of grappling with mortality, guilt, and redemption. Following the 1968 shooting, he turned toward devotional subjects, culminating in the Last Supper series (1986–87), which reimagined Leonardo da Vinci’s icon through silkscreened repetition and saturated color palettes (Warhol Foundation; “Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDS”). In these sixteen canvases, Warhol layered text, words such as “eat,” “drink,” and “drink this”,.over the central image of Christ, merging sacred narrative with commercial language to evoke both communion and commodification. Warhol explained that he chose the Last Supper as a subject because “it hit me that everyone you know and love is going to die,” signaling his confrontation with the AIDS epidemic ravaging his community (Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDS). Art historians interpret these works as a queer confession; an appeal for collective salvation in the face of a crisis that branded gay bodies as contagious and immoral (Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDS; Hyperallergic 2).

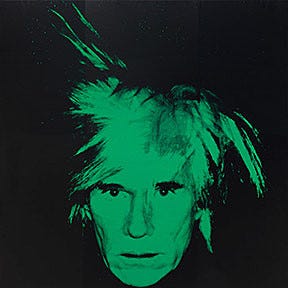

Concurrently, Warhol produced numerous self-portraits in which he obscured his face behind masks, scarves, or heavy makeup, gestures that underscore identity’s performative aspects. In his 1986 Self-Portrait (Front), Warhol depicts himself gazing directly at the viewer, bleary-eyed, his pale skin and white wig illuminated against a dark background, conveying both vulnerability and defiance (Warhol Museum). These late self-portraits, rendered in Polaroid, acrylic, and silkscreen, emerged amid the height of the AIDS crisis, reflecting Warhol’s personal fears and the broader community’s desperation.

Warhol died on February 22, 1987, from complications following gallbladder surgery. His passing occurred as the AIDS epidemic claimed tens of thousands of lives, disproportionately affecting gay men (“HIV and AIDS Overview”). Though Warhol never disclosed an HIV status, his diaries and late works reveal a profound preoccupation with the disease’s impact on his friends and collaborators (Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDS). In the immediate aftermath of his death, Warhol’s persona as a gay icon solidified: exhibitions such as Pop Out: Queer Warhol (Duke University Press, 1996) and retrospectives at The Andy Warhol Museum emphasized his role in visualizing queer desire and challenging normative identity constructs (Pop Out: Queer Warhol; Them.us Editors).

Warhol’s legacy extends beyond his lifetime through his influence on subsequent queer artists who further explored themes of sexuality, identity, and mortality. Robert Mapplethorpe’s black-and-white photographs of homoerotic subjects and Felix González-Torres’s minimalist installations reflecting the AIDS crisis trace lineage to Warhol’s blending of commercial technique with queer content (Hyperallergic 1). More recently, exhibitions such as “Becoming Queer: Warhol in the 1950s” at the Whitney Museum have reappraised Warhol’s early work, foregrounding his foundational role in crafting a visual language for gay desire amid McCarthy-era repression (“Becoming Queer: Warhol in the 1950s”).

Andy Warhol’s career, spanning commercial illustration, painting, film, and publishing, was inseparable from his LGBTQ identity, even as he publicly cultivated an aura of detachment. Through his early Boy Book drawings, he tenderly depicted male beauty at a time when homosexuality was criminalized. His Pop-inflected portraits of drag icons and disco stars in the 1970s championed queer visibility amid a mainstream culture still resistant to non-normative identities. The Factory’s ethos of collaborative performance created a haven for queer creativity that reverberated throughout his filmic and photographic practices. In his late years, Warhol’s turn to religious iconography and self-portraiture confronted the specter of illness and death cast by the AIDS crisis, producing some of his most candid reflections on desire, fear, and faith. By destabilizing binaries, high art versus consumer culture, sacred versus profane, heteronormative versus queer, Warhol not only transformed art history but also paved the way for future generations of LGBTQ artists to explore identity on their own terms. His legacy persists in contemporary discourses on the politics of representation, reminding us that art can both mirror and subvert prevailing cultural narratives.

References:

Andy Warhol. Biography.com, A&E Television Networks, 25 Aug. 2021, biography.com/artists/andy-warhol. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (Bryn Mawr College Repository)

Becoming Queer: Warhol in the 1950s. The Whitney Museum of American Art, www.whitney.org/events/becoming-queer-warhol-1950s. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.(Whitney Museum)

Boy Book Drawings. The Andy Warhol Museum, warhol.org/lgbtq/. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (JSTOR)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS Overview. CDC.gov, 2024, cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

Colacello, Bob. Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up. HarperCollins, 2000.

Gopnik, Blake. Warhol. Ecco, 2020.

Hyperallergic. Andy Warhol's Defiant Hopes for Queer Art. 18 Jan. 2021, hyperallergic.com/613511/andy-warhol-queer-art-blake-gopnik/. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (Hyperallergic)

Pop Out: Queer Warhol. Duke University Press, read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/1800/Pop-OutQueer-Warhol. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (Duke University Press)

Revolver Warhol Gallery. Presence and Absence: Andy Warhol’s Sexual Identity as Seen in His Body. RevolverWarholGallery.com, 10 Jan. 2021, revolverwarholgallery.com/presence-and-absence-andy-warhols-sexual-identity. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

Them.us Editors. Remembering Candy Darling, a Trailblazing Trans Warhol Muse and Unlikely Star. Them.us, them.us/story/candy-darling-cynthia-carr-warhol. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

The Biography of Andy Warhol. The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, warholfoundation.org/warhol/. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (AGSA)

Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDS. The Andy Warhol Museum, warhol.org/warhols-confession-love-faith-and-aids/. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (The Andy Warhol Museum)

Warhol, Andy, and Pat Hackett. POPism: The Warhol ’60s. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980.

Warhol, Andy, and Pat Hackett. The Andy Warhol Diaries. Edited by Pat Hackett, Warner Books, 1989.

Warholstars.org. Studies for a Boy Book. warholstars.org/works/boy_book.html. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

Warholstars.org. Warhol Superstars. warholstars.org/superstars.html. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia contributors. Valerie Solanas. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 May 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valerie_Solanas. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025. (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia contributors. Andy Warhol. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andy_Warhol. Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.(The Andy Warhol Museum)

Great read!! I really was taken back to my early days going to school in NYC when there were still remnants of the ‘Warhol Effect’ in the village. I remember going to The Waverly to see movies with Divine. He wasn’t dead yet and the shooting was a big deal.

Life was simpler then, though we didn’t know it. Being creative at the volume he produced was unheard of. Now it’s normal.

Thanks for a fresh look at this controversial persona and moment in art history.