Art movements have long been a reflection of the changing social, political, and intellectual climates. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, two significant movements emerged in Europe, Romanticism and Realism, each reshaping artistic expression in response to the upheavals of the time. While Romanticism emphasized emotion, nature, and individual experience, Realism sought to depict the everyday life of ordinary people with an unflinching commitment to truth. These movements both reacted against earlier artistic conventions, yet each approached the human experience from radically different angles.

Romanticism, which emerged in the late 18th century and flourished into the 19th century, was a profound shift away from the rational and restrained ideals of Neoclassicism. At its core, Romanticism celebrated deep emotion, the sublime in nature, and individual experience. It arose as a counter-movement to the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason, and to the societal changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, which reshaped the European landscape (Britannica). Romantic artists sought to reconnect with nature in a way that evoked awe, wonder, and sometimes fear. They viewed nature not as a mere backdrop, but as a dynamic force intertwined with human existence, often exploring the tension between man and the overwhelming forces of the natural world.

The Romantic movement was also deeply influenced by political upheavals such as the French Revolution, which called for the liberation of the individual and a rethinking of societal structures. Artists like Caspar David Friedrich and J. M. W. Turner expressed these ideals through their works. Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818) captures the solitary figure of a man gazing out over a misty, vast landscape, conveying a sense of existential reflection. In contrast, Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway (1844) merges the raw power of nature with the burgeoning influence of industry, presenting a dynamic and emotional response to the industrialization of England (Tate).

Romanticism was not confined to landscapes. Artists such as Eugène Delacroix employed historical and literary sources to infuse their works with emotion and symbolism. Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) encapsulates revolutionary fervor, using vivid colors and dynamic composition to evoke passion and a call for freedom (Smarthistory). Romantic art also had a significant presence in sculpture, with artists like Antonio Canova and Bertel Thorvaldsen softening classical forms to convey more expressive human figures, bridging the Neoclassical and Romantic worlds.

The influence of Romanticism extended beyond visual arts into literature and music, where figures like William Wordsworth and Ludwig van Beethoven explored similar themes of nature and emotion. As a movement, Romanticism not only altered the course of art history but also shaped broader cultural values, emphasizing the importance of individual perception, the transformative power of beauty, and the profound connection between humanity and nature.

In contrast to the emotional intensity of Romanticism, Realism emerged in the mid-19th century as a direct response to both the idealization of the past and the social changes of the Industrial Revolution. While Romantic artists focused on dramatic, often exaggerated representations of nature and human emotion, Realist artists sought to depict life as it truly was, without embellishment or glorification. The movement, which gained prominence in France during the 1840s, arose from a desire to represent the lives of ordinary people and to confront social issues head-on (The Art Story).

At the heart of Realism was a commitment to truth and accuracy. Realist artists like Gustave Courbet rejected the idealized depictions of historical or mythological subjects favored by the Academy and instead focused on the everyday lives of common people. Courbet’s The Stone Breakers (1849) depicts two laborers at work, their bodies marked by the harsh realities of manual labor. This straightforward portrayal of the working class was a stark contrast to the romanticized depictions of poverty and labor found in earlier art (Britannica). Similarly, Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners (1857) shows three women collecting leftover grains after the harvest, highlighting the dignity and hardship of rural life.

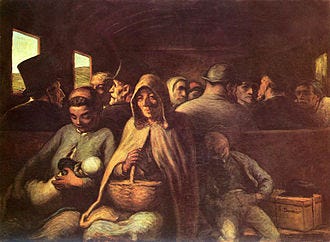

Realism was also defined by its social commentary, as artists sought to bring attention to the plight of the underprivileged and the injustices of their time. Honoré Daumier’s The Third-Class Carriage (1862–1864) depicts the cramped, uncomfortable conditions of lower-class passengers in a train, critiquing the social stratification of 19th-century France (Metmuseum.org). Realist artists rejected the emotional idealism of Romanticism, opting instead for a raw, unflinching examination of their society.

The influence of Realism extended beyond visual art, impacting literature and theater. Writers such as Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola followed in the footsteps of Realist painters, focusing on the lives of ordinary people and exploring social and moral issues in their works. Moreover, the techniques of Realism influenced later movements such as Impressionism, Social Realism, and Photorealism, all of which continued to explore themes of everyday life, often with a focus on social change and human experience (Gutu).

While both Romanticism and Realism were reactions against earlier artistic movements, they diverged significantly in their approach. Romanticism embraced the subjective experience, focusing on the emotional and spiritual aspects of life, often portraying nature as an overwhelming, sublime force. In contrast, Realism sought to depict the world with precision, emphasizing accuracy and the representation of ordinary life. Romanticism was concerned with the vastness of human emotion and the sublime in nature, while Realism was rooted in the daily struggles and realities of the working class.

The legacies of both movements are profound. Romanticism’s emphasis on emotion, nature, and individuality continues to resonate today, influencing modern art and culture. Romantic works still captivate audiences with their emotional intensity and awe-inspiring depictions of nature. Realism, on the other hand, laid the groundwork for subsequent art movements that focused on social issues and the representation of everyday life. Its emphasis on authenticity and truthful representation remains influential in contemporary art, particularly in movements like Photorealism.

Romanticism and Realism were two of the most significant artistic movements of the 19th century, each offering a unique perspective on the human experience. Romanticism celebrated emotion, individualism, and the sublime in nature, while Realism focused on the accurate portrayal of ordinary life and social issues. Both movements challenged the established norms of their time, leaving lasting marks on the course of art history. Together, they provided a rich tapestry of responses to the changing world, highlighting the complexity of human emotion and the struggle for truth in art.

References:

Realism. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/art/realism-art.

Realism Movement Overview. The Art Story, https://www.theartstory.org/movement/realism/.

Realism (Art Movement). Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Realism_(art_movement).

Gutu, Mihaela. What Impact Did Realism Have on Society? TheCollector, 20 Apr. 2024, https://www.thecollector.com/realism-impact-society/.

The Third-Class Carriage. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rlsm/hd_rlsm.htm.

Romanticism: Emotion and Nature. Smarthistory, https://smarthistory.org/romanticism/.

Romanticism. Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/r/romanticism.

Romanticism. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/art/Romanticism.

Romantic Art. Khan Academy, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-history-basics/beginners-art-history/romanticism/a/romanticism-overview. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

Romanticism. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/roma/hd_roma.htm. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

Romanticism in Art: An Overview. Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/s/explore/collection/area/romanticism. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

I wonder what they will call this age of art?

Bluescreenism.

A.i-ism

Digitalism

Something that has always fascinated me about both the Corbet, and Millet paintings is the light. Corbet feels like studio light even though it is an out door scene, but what I find interesting in both is the dark contrasting shadow. On the Corbet Painting it's like a dark foreboding cloud hovering over the top half of the image. On the Millet painting it's similar but creepiing in from the bottom right. On both paintings it is as though there is possibly some menacing dark force trying to overshadow the daily routines of the people in each.