Bridge of No Return: Ichabod’s Last Light

#31daysofhalloween

Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1819–20) offered American artists a ready-made repertory of images (moonlit lanes, gnarled trees, a teetering schoolmaster, and a headless rider) that could translate post-Revolutionary anxieties into Romantic scenery. Painters and printmakers in the Hudson River Valley, foremost John Quidor and illustrator F. O. C. Darley, converted Irving’s Dutch-colonial folklore into a distinctly American Gothic; landscapes that perform conscience, uniforms that haunt without bodies, and a pumpkin that doubles as both harvest bounty and ballistic terror.

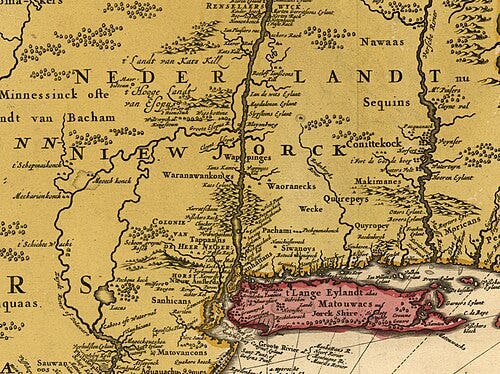

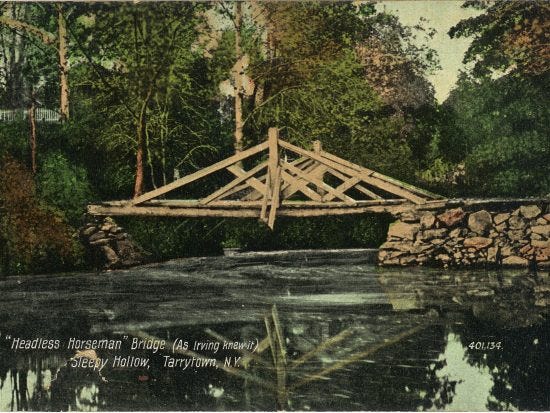

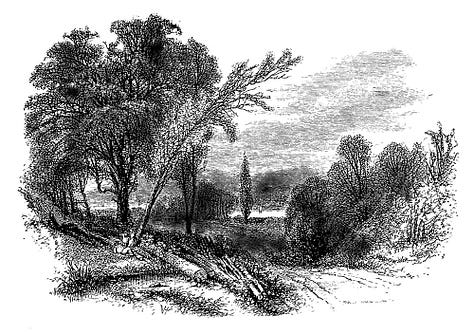

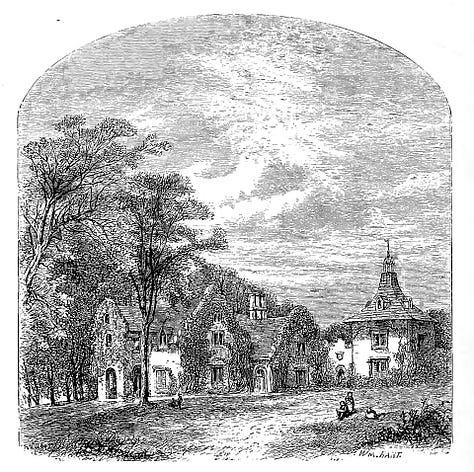

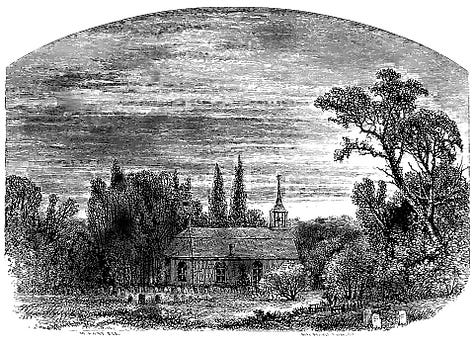

Irving anchors Sleepy Hollow in a Dutch-American enclave colored by Calvinist dread, its churchyard, bridge, and farms nested in “a sequestered glen” where superstition outruns Enlightenment (Irving). John Quidor’s Ichabod Crane Flying from the Headless Horseman (ca. 1828, Yale) and The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane (1858, SAAM) transpose that prose to canvas; willow, church spire, and lane become agents of fear, while caricature calibrates terror to comedy. The Old Dutch Church’s continuous history and burial ground fix Irving’s folklore to verifiable place, giving artists a Gothic stage with documentary weight. (Irving; Quidor at SAAM; Quidor at Yale; Reformed Church history.)

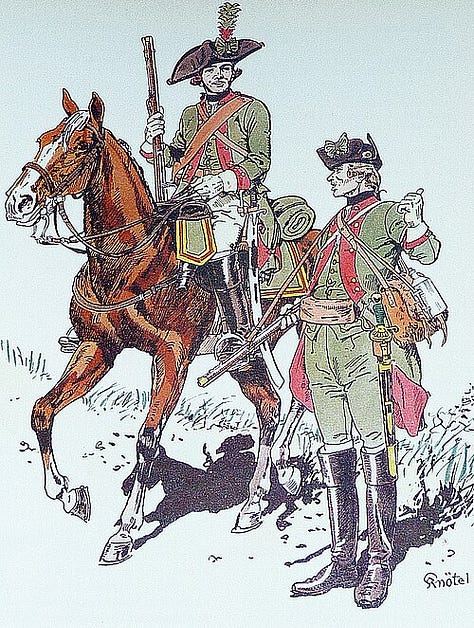

The Horseman’s missing head points to war residue. The foreign mercenary as long after-image in domestic space. Revolutionary-era depictions of Hessians; Trumbull’s Capture of the Hessians at Trenton (YUAG) and contemporary surviving headgear (miter/mitre caps and cap plates) preserved at the National Museum of American History and the Museum of the American Revolution, document how German auxiliaries looked and were remembered. Those helmets, sabers, and tack reappear as floating regalia in Headless imagery, a visual mnemonic that domestic tranquility sits atop imported violence. (Trumbull; NMAH miter cap; Museum of the American Revolution cap plates.)

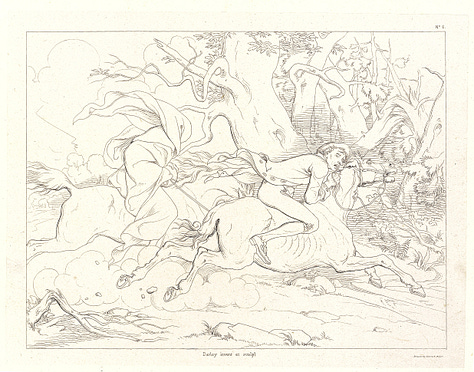

Early republic visual culture is crowded with decapitations; of monarchs in European prints, of reason from appetite in American satire. In Sleepy Hollow pictures, decapitation doubles as a political allegory; horsepower without a guiding head. Quidor’s 1858 composition pushes the rider’s torque forward while withholding the head, staging a republic that fears speed ungoverned by reason. The allegory resonates with Trumbull’s grand canvases of surrender and statecraft, whose pageantry of officers and standards model the opposite; heads firmly attached to order. (Quidor; Trumbull’s Surrender of Burgoyne and related objects at the AOC and Met.)

The Hudson Valley is layered. Colonial roads laid over Indigenous paths; churchyards on earlier grounds. Local histories identify the Weckquaesgeek (Wappinger) presence in the Tarrytown–Sleepy Hollow area, while the Albany Post Road followed Native routes before improvement. Artists capitalized on this layered text. Crooked lanes and thresholds read as sites where displacements return as apparitions. That palimpsest intensifies the Gothic; the landscape is not backdrop but archive. (Village of Tarrytown history; NPS heritage documentation.)

Uniform pieces outlive bodies, helmets, cap plates, sabers, and tack function as detached insignia. In Headless scenes, these become floating signs of command severed from conscience; a critique legible to audiences familiar with Hessian hardware via prints, museums, and veterans’ lore. The metonymy is documentary; viewers could recognize a fusilier’s miter front or dragoon tack in Darley’s etched detail. (Museum of the American Revolution cap plates; NMAH.)

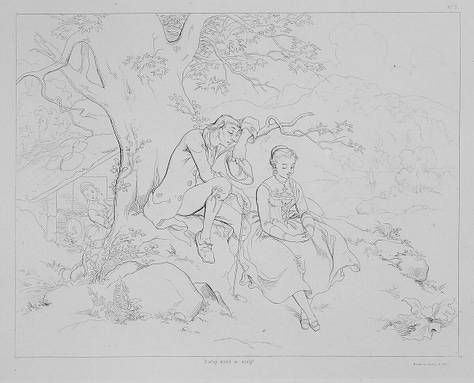

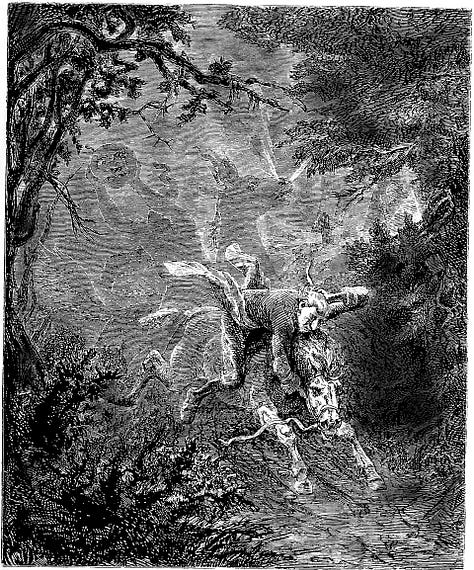

Darley’s six-plate Illustrations of the Legend of Sleepy Hollow (American Art-Union 1849–50), printed by Sarony & Major and circulated to thousands of subscribers, fix buttons, braids, and cavalry trim with journalistic exactitude. That tactile accuracy anchors the supernatural in period fact, making fear plausible by tying it to recognizable cloth and leather. (AAS/AHPCS documentation; Met object record; 1849 portfolio at MFA Boston.)

Irving’s text specifies the pumpkin/puncheon as missile and masquerade; images sharpen the point by painting a grinning gourd as ersatz cranium; abundance weaponized. In Quidor’s SAAM picture, the pumpkin arcs toward Ichabod at the bridge; a counterfeit head that turns commodity culture into terror and literalizes the story’s prank-versus-phantom ambiguity. (Irving; SAAM.)

Funerary motifs (willow, obelisk, spire) often smuggle themselves into chase scenes. Quidor’s earliest Yale canvas lets trees and tomb-like verticals do the moralizing. Artists borrow vanitas codes to fold comedy back into mortality; the chase itself becomes a moving grave. (YUAG; SAAM labels noting evening/landscape and literary context.)

Hudson Valley woods become stage machinery; proscenium branches and scrims of mist. The Met’s overview of nineteenth-century American landscape painting shows how painters formalized nature to carry narrative and ethics; Sleepy Hollow scenes exploit that dramaturgy, swapping sublime sunrise for nocturne and suspense. (Met, “Hudson River School”/American landscape overview.)

Irving’s covered-bridge lore met local topography where the precise status of a “covered bridge” in Sleepy Hollow remains debated; historians note no hard evidence the crossing was ever covered, though a bridge at the mill existed. Artists tighten the chase at such thresholds (bridges, crossroads, church gates) where law and superstition trade jurisdiction. (Sleepy Hollow Country; Reformed Church site on the mill/bridge environs.)

Water crossings read as trials. Reflections distort, moons warp, silhouettes ripple. In images keyed to Irving’s description, the dash for the bridge becomes a rite of passage Ichabod fails; his “deliverance” is a dunking into the comic-tragic modern. (Irving; Darley’s plate sequences culminating near the bridge.)

Sudden squalls, ragged clouds, storm-scarred trees; landscape behaves like conscience. American Romantic painters often moralized weather; Sleepy Hollow’s nocturnes iterate that code with comic torque. The economy of sky in Darley’s lithographs and the tree drama in Quidor’s canvases make temperament meteorological. (Met landscape overview; SAAM/YUAG records.)

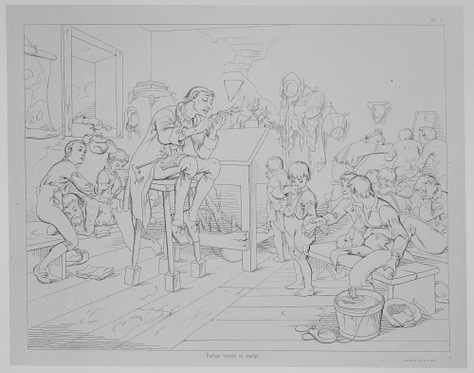

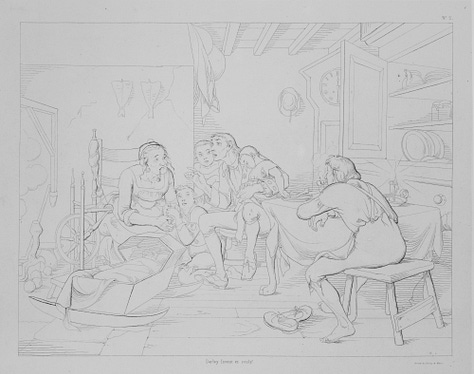

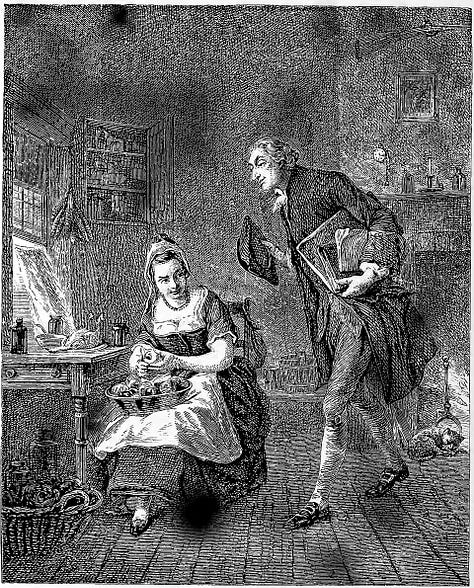

A nocturne in three lights governs Sleepy Hollow iconography; candle (human scale), moon (fate), gun-flash (shock). Gift-book culture taught readers to read such hierarchies; Darley’s plates stage candlelit interiors (Katrina’s parlor, the schoolroom) against moonlit lanes to script speed and morality. (AAS Past-is-Present on illustrated editions; Darley plates.)

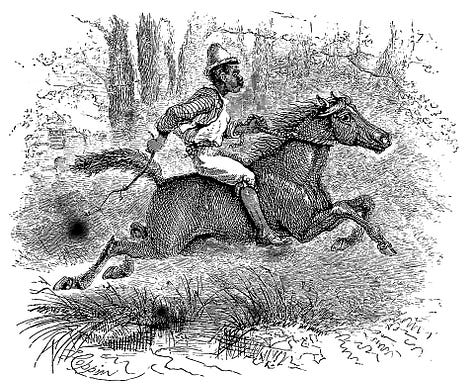

Artists visualize hooves, rattling tack, and wind via repeated parallel strokes, dust plumes, and vibrating foliage. Darley’s diagonals and broken outlines supply on-paper acoustics; Quidor’s whipping willow and stretched gesture do the same in oil. (Met Darley record; SAAM label.)

A limited palette, orange shock against midnight woods, does psychological work. The chromatic clash makes the counterfeit head “speak,” while grave blacks absorb reason. Quidor’s SAAM painting is exemplary; orange projectile, black horse mass, white steed; a triad of appetite, dread, and flight. (SAAM.)

Headless imagery pushes equine anatomy forward: flared nostrils, bunched shoulders, motion blur. The animal becomes the engine of terror; rider a vacancy riding it. Quidor’s canvases exaggerate musculature; Darley’s plates rake diagonals to let the horse carry the narrative. (SAAM; Met Darley.)

Comic terror depends on contrast; a spindly schoolmaster as negative space against the Horseman’s mass. Caricature, far from softening dread, is a Romantic device that intensifies it by calibrating scale and weight. Darley’s Ichabod and Katrina and classroom scenes establish that stick-figure fragility long before the chase. (Darley, Plate 3; AAS blog on Darley’s Sketch Book illustrations.)

Whip-pan compositions, diagonal thrusts, and torn edges in lithographs make the Horseman an early meditation on velocity and media rhythms. The American Art-Union’s mass distribution, tens of thousands of subscribers, trained eyes to read narrative speed in print before oil monumentalized it. (AAU membership/print culture; Orcutt on AAU and reproduction.)

Katrina’s parlor and the church green operate as stages of surveillance and spectacle. The 1863 illustrated Sketch-Book plates, by Emanuel Leutze, John F. Kensett, William Hart, T. Addison Richards, and others, map flirtation and gossip as fuel for the chase, toggling between interior satire and exterior sublime. (1863 illustrated edition plate list.)

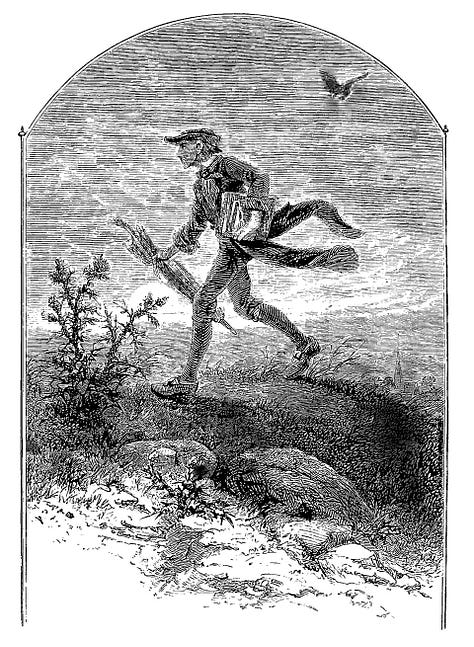

Orchards, fences, scarecrows act as accomplices; vernacular objects become uncanny witnesses or weapons. Darley and his contemporaries, via gift-book and Art-Union channels, rehearse a visual literacy of “everyday Gothic,” where farm fixtures tilt toward menace at night. (AAS/AHPCS documentation; Met book.)

The circulation of terror matters. Annuals, keepsakes, and AAU portfolios seeded imagery across parlors before canvases entered museums. Darley’s 1849 Sleepy Hollow suite (Sarony & Major; Trow) and the 1863 Putnam gift-book plates taught audiences how to see the chase; Quidor then monumentalized those habits in oil. (AAS/AHPCS; MFA Boston; 1863 plate list.)

Humor is a delivery system for the uncanny. SAAM’s label for Quidor calls Ichabod a “pompous twit,” an interpretive cue that frames comedy as the whetstone for dread; laughter thins defenses so the nocturne can bite. (SAAM.)

Post-impact iconography; abandoned hat, shattered pumpkin, broken reins reads as Romantic vanitas. Artists and illustrators linger on aftermath still lifes to moralize appetite, reason, and reputation as perishable goods. The AAU plates and later gift-books codify these motifs for a broad audience. (AAU/AHPCS; AAS blog.)

Romantic fragmentation structures the series; head excised (reason), while appetite (pumpkin/orange) and action (horsepower) run amok. The image ecology mirrors cultural debates Goddu and the Cambridge scholarship identify in the American Gothic; a nation staging its own divided self in landscape and body. (Goddu; Cambridge Companion.)

Borrowed European Gothic tropes mutate at the frontier’s edge. With Dutch folklore, Hessian hardware, and Yankee print capitalism, the Headless Horseman becomes a hybrid American grotesque; half satire, half sublime. Landscapes moralize, costumes testify, and speed modernizes terror. The result is an art-historical through-line from Quidor’s canvases and Darley’s portfolios to later nocturnes and popular iconography. Sleepy Hollow proves how a republic pictures fear to test its ethics. (Quidor; Darley; AAU; Met landscape essay.)

Early American Romantic artists did not merely illustrate Irving; they engineered a visual system that made his tale an instrument for national self-reflection. Works by Quidor and Darley, grounded in the real topography of Sleepy Hollow and the material culture of the Revolutionary War, turn folklore into political allegory and commodity culture into moral theater. The Headless Horseman is thus less a monster than a method; a way for American art to think, about power without conscience, history without memory, and speed without governance, by painting, printing, and widely circulating the chase. (Irving; Quidor; Darley; Reformed Church; AAU.)

References:

American Antiquarian Society. The Many Faces of the Headless Horseman: Illustrations of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Past is Present (blog), 29 Oct. 2015.

American Historical Print Collectors Society (AHPCS). The American Art-Union. ahpcs.org.

Architect of the Capitol. Surrender of General Burgoyne. aoc.gov.

Darley, Felix O. C. Washington Irving’s Illustrations of the Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Designed and Etched for the Members of the American Art-Union, 1849–50. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession 44.40.2.

Illustrations of the Legend of Sleepy Hollow. New York: American Art-Union, 1849. Digital facsimile, Internet Archive.

Goddu, Teresa A. Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation. Columbia University Press, 1997.

Irving, Washington. The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. In The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., 1819–20. Project Gutenberg, updated 27 June 2022.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. American Landscape Painting in the Nineteenth Century. Timeline of Art History.

Museum of the American Revolution. Hessian Cap Plates.

National Museum of American History (Smithsonian). Hessian Miter Cap.

Quidor, John. The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane. 1858. Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Object record.

Ichabod Crane Flying from the Headless Horseman. ca. 1828. Oil on canvas. Yale University Art Gallery. Object record.

Reformed Church of the Tarrytowns. History of the Old Dutch Church.

Sleepy Hollow Country. Which Bridge?

Tarrytown, NY (Official Village Site). History of the Village of Tarrytown.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, New York. Print after John Trumbull. Object record.

Yale University Art Gallery. John Trumbull, The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, December 26, 1776. Object record.

Yale University Art Gallery. John Quidor, Ichabod Crane Flying from the Headless Horseman. Object record.

Hart, William (after J. H. Hill), Church at Sleepy Hollow; Kensett, John F., The Tappan Zee; Leutze, Emanuel, Brom Bones and Ichabod Crane; Richards, T. Addison, The Old Schoolhouse; Hoppin, A., The Messenger. In The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. New York: G. P. Putnam, 1863. Plate list verified in the digitized edition.

I enjoyed the story and artwork associated with my favorite tales