The evolution of graffiti in the late twentieth century reflects a complex interplay between subversive self-expression and mainstream cultural validation. Within this dynamic landscape, Lady Pink emerges as a transformative figure whose work transcends the confines of mere tagging to embody a powerful narrative of rebellion, empowerment, and identity. As one of the first women to assert her presence in New York City’s graffiti scene, Lady Pink’s trajectory, from illicit subway art to inclusion in museum collections, mirrors the broader societal shifts regarding art, gender, and urban public space (National Museum of African American History and Culture; Wikipedia [English]).

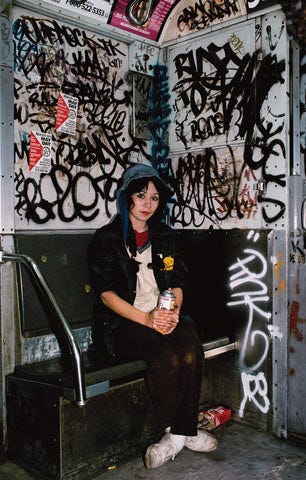

Sandra Fabara was born in Ambato, Ecuador, in 1964 and immigrated to the United States at the age of seven, settling in Queens, New York. Growing up in a culturally diverse and rapidly changing urban environment, she was exposed to the burgeoning hip-hop culture and the nascent world of graffiti during the late 1970s. Her early exposure to art came not only from the vibrant street life of New York but also from a personal determination to process loss and assert her identity. In 1979, after the painful breakup of a relationship, she began tagging subway trains; a decision that would eventually cement her status as a pioneer (National Museum of African American History and Culture; LadyPinkNYC).

Choosing the name “Lady Pink” was a deliberate act of self-identification and resistance. As explained in interviews and documented on Wikipedia, the moniker was given by fellow graffiti writer Seen TC5 and symbolized both her femininity and her defiance of gender norms in a medium dominated by young men (Wikipedia [English]; Latina). These formative experiences, combined with her immigrant background and exposure to diverse cultural influences, instilled in her an enduring drive to reclaim urban space for artistic expression.

Lady Pink’s artistic career swiftly evolved from spontaneous subway tags to elaborate compositions that merged raw street aesthetics with refined artistic techniques. In the early 1980s, her work appeared on New York City’s subway trains; a subject documented in seminal texts such as Subway Art by Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant (Cooper and Chalfant). Her participation in the landmark film Wild Style (1982) further amplified her profile, positioning her as a key figure in both hip-hop culture and the emerging world of street art (Darzin).

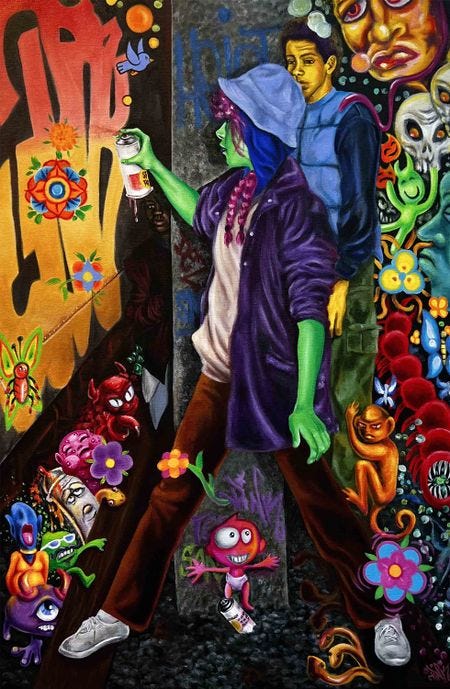

Over time, Lady Pink expanded her practice beyond the ephemeral nature of subway art. By the mid-1980s, she began exhibiting in galleries and executing commissioned murals. Her canvases, characterized by dynamic wildstyle lettering, bold color palettes, and recurrent motifs such as empowered female figures and urban iconography, have been acquired by major institutions including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn Museum; Artnet). Nicholas Ganz’s Graffiti Women: Street Art from Five Continents (2006) situates her work within a global narrative, noting that her pioneering style has inspired generations of female street artists worldwide.

One of the most striking aspects of Lady Pink’s legacy is her complex relationship with feminist activism. Entering the graffiti scene in a milieu that was not only male-dominated but also steeped in hyper-masculine stereotypes, she quickly found that her presence challenged both social and artistic norms. Although she has often refrained from labeling herself a militant feminist, her work, rich in figurative imagery and satirical commentary, has become emblematic of women’s resistance in the public sphere (Cascone; Feminist Activism in Hip-Hop [Wikipedia]).

Her art frequently features strong, assertive female figures rendered with playful defiance and meticulous detail. In interviews such as Sarah Cascone’s 2019 Artnet News piece, Lady Pink reflects on how her early work inadvertently embraced feminist themes, stating, “I was a feminist before I even knew what the word was” (Cascone). Scholars like Gupta-Carlson have noted that graffiti by women often functions as a tool for community building and empowerment (Gupta-Carlson). Additionally, the annual Femme Fierce events and related documentaries, such as Women on Walls (2014), underscore the growing recognition of female voices in street art (Nydia Pabón-Colón).

By mentoring young artists and engaging in community-based projects, Lady Pink has transformed her personal experiences into a broader social dialogue, challenging the erasure of women in the history of graffiti and affirming the right of women to claim public space.

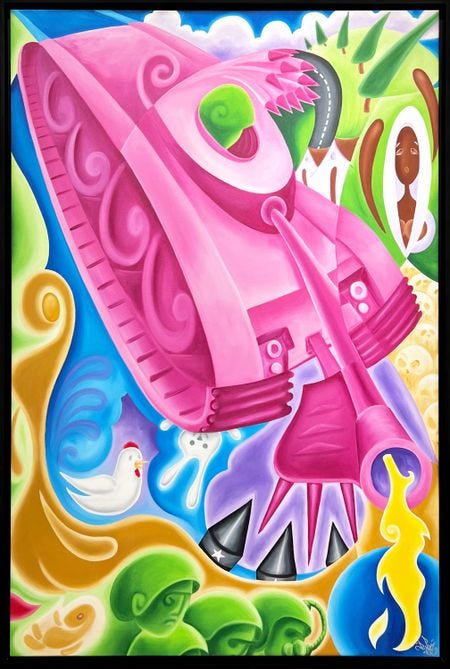

Lady Pink’s journey from the gritty subways of New York to the polished halls of major art institutions underscores a critical transformation in the art world. Her “Death of Graffiti” series, for example, is a poignant meditation on the impermanence of street art in the face of urban renewal and regulatory suppression (The Death of Graffiti; Barnett). By incorporating recurring elements such as train cars, artist tags, and symbolic nude figures, she not only documents the history of graffiti but also reasserts the vitality of the medium.

Major museums now house her works, signaling a paradigm shift in which graffiti is recognized as a legitimate and influential form of contemporary art. The destruction of 5Pointz in Queens, a landmark moment in graffiti history, further underscores the vulnerability and transient nature of street art, while legal victories (such as the $6.75 million award upheld for affected artists) have established its cultural value (Kinsella). Furthermore, PBS NewsHour recently highlighted Lady Pink’s groundbreaking contributions to urban art, noting that her career embodies both the rebellious spirit of graffiti and its eventual institutional validation ("The Groundbreaking Work of Ecuadorian American Graffiti Artist Lady Pink").

Beyond her prolific output as an artist, Lady Pink’s enduring legacy is equally defined by her commitment to education and mentorship. For decades, she has conducted mural workshops, lectured at universities, and inspired countless young artists to pursue their creative visions. Her work with the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts in Queens, where she helps students build portfolios and secure scholarships, has been widely recognized as a critical force for community empowerment (Park; National Endowment for the Arts).

Her influence has extended internationally, prompting scholarly inquiry into the intersections of urban art, gender politics, and cultural memory. Academic articles such as Jonathan Gross’s “Lord Byron and Lady Pink: An Orlando Story of Two Graffiti Artists” (2022) offer nuanced analyses of her role in shaping graffiti’s cultural narrative. Additionally, discussions in venues such as Graffiti Women: Street Art from Five Continents have cemented her status as an icon whose work continues to challenge and redefine the boundaries between underground aesthetics and high art.

Lady Pink’s career is a multifaceted chronicle of artistic evolution, social defiance, and cultural transformation. From her humble beginnings tagging New York City subway trains to her current stature as a celebrated muralist and mentor, she has continuously redefined the language of urban art. By integrating raw street energy with a sophisticated visual vocabulary, and by embracing themes of feminism, community, and resilience, Lady Pink not only transformed the aesthetics of graffiti but also reimagined its cultural and political possibilities. Her work remains an enduring testament to the power of art as a vehicle for social change, inspiring future generations to challenge conventional boundaries and assert their creative identities.

References:

Artnet News. I Was a Feminist and I Didn’t Know It: How Lady Pink Made a Space for Herself in the Boys Club of New York’s Graffiti Scene. Artnet News, 17 July 2019, news.artnet.com/art-world/lady-pink-interview-1602208. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Barnett, Claudia. The Death of Graffiti: Postmodernism and the New York City Subway. Studies in Popular Culture, vol. 16, no. 2, 1994, pp. 25–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23413729.

Brooklyn Museum. Lady Pink. Brooklyn Museum, www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/about/feminist_art_base/lady-pink. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Cascone, Sarah. I Was a Feminist and I Didn’t Know It: How Lady Pink Made a Space for Herself in the Boys Club of New York’s Graffiti Scene. Artnet News, 17 July 2019, news.artnet.com/art-world/lady-pink-interview-1602208. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Cooper, Martha, and Henry Chalfant. Subway Art. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1984.

Feminist Activism in Hip-Hop. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_activism_in_hip-hop. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Gupta-Carlson, Himanee. Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop. New Political Science, Dec. 2010.

Gross, Jonathan. Lord Byron and Lady Pink: An Orlando Story of Two Graffiti Artists. The International Journal of Social, Political and Community Agendas in the Arts, vol. 17, no. 2, 2022, pp. 1–17, doi:10.18848/2326-9960/CGP/v17i02/1-17.

LadyPinkNYC. About. LadyPinkNYC, www.ladypinknyc.com/about. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

National Endowment for the Arts. Pure Expression: Lady Pink and the Evolution of Street Art. NEA, Feb. 2013, www.arts.gov/stories/magazine/2013/2/ahead-their-time/pure-expression. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

National Museum of African American History and Culture. Lady Pink. NMAAHC, 11 Jan. 2022, nmaahc.si.edu/latinx/lady-pink. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

PBS NewsHour. The Groundbreaking Work of Ecuadorian American Graffiti Artist Lady Pink. PBS NewsHour, 2023, www.pbs.org/newshour/show/the-groundbreaking-work-of-ecuadorian-american-graffiti-artist-lady-pink. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Wikipedia. Lady Pink. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Pink. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Wikipedia. The Death of Graffiti. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Death_of_Graffiti. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

What a woman!!!

Great write up on Lady Pink, I would also say that she extended and revived our community by not just participating with us. But by having sheer determination to be included and respected among us. She made herself known and seen in the moment never allowing space to fade her.

We as a community are so focused on “me” we forget there is space for “we” to embrace our female creatives. It’s always been a hovering question “where did all the girl writers go?”

I knew they existed, I saw their tags, Barbra, Eva and so on. But where are they? It seemed fitting to me they would be there whenever I arrived at Writers Bench unfortunately that was not the case.

When I met Pink we hit it off, her energy was and still is electric. The colorful and playful nature of her personality was evident and sparked interest to paint cars with her. The Randy Sandy car found its light on a Sunday afternoon in the Ghost Yard.

Our early pre-hip-hop and Roxy days opened doors for many forms of creative outlets Lady Pink was one at its entrance. As hip-hop was yet to be discovered in those early days because it was known as a mere slogan shouted out in rare mc lyrics until it found its place to be commercialized in 1980 by recording labels and mc’s turned rappers.