Breaking the Frame: The Unseen Contributions of Women Artists in a Male-Dominated World

Art history has long been dominated by male-centered narratives that emphasize individual genius while relegating women’s contributions to peripheral status. Early modern institutions, including the Bauhaus, promised equal opportunity but often confined female students to “appropriate” disciplines such as weaving and ceramics (Katsarova; Baumhoff). Linda Nochlin’s influential essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” challenged these historical omissions by arguing that the absence of recognized female genius was the result of institutional obstacles rather than inherent incapacity (Nochlin 22–39).

Beyond individual cases, the issue extends to the broader cultural construction of art itself. Feminist art historians have argued that the very definitions of artistic creativity and the criteria for “greatness” have been formulated within a patriarchal framework. This framework privileges the traits associated with masculinity, such as assertiveness, individualism, and technical mastery, while sidelining the collaborative and process-oriented approaches more commonly embraced by women (Pollock). Furthermore, the persistence of gender bias in art education and museum collections reflects broader societal norms that continue to influence academic discourse and art market dynamics. These multifaceted challenges call for a reexamination of the traditional canon, urging art historians to develop more inclusive methodologies that capture the full spectrum of artistic innovation.

The introduction also sets the stage for a discussion of how feminist theory has not only critiqued past inequities but has also inspired contemporary efforts to reshape institutional practices. Recent initiatives, from specialized exhibitions and revised art curricula to digital platforms that democratize art criticism, demonstrate that the legacy of gendered exclusion is being actively contested.

Traditional gender roles have long determined which artists are celebrated and which remain on the periphery of art history. Linda Nochlin’s essay famously contends that the myth of the “great artist” is inextricably linked to patriarchal ideals that valorize male creativity while denying women the opportunity to develop their talents (Nochlin 22–39). This imbalance is further compounded by the tendency of art institutions and museums to curate exhibitions that prioritize works by male artists, relegating the contributions of women to side notes or adjunct collections (Broude and Garrard 471–490).

Moreover, cultural stereotypes have often reduced women artists to mere decorative figures or muses rather than positioning them as independent creators. Griselda Pollock’s work emphasizes that this marginalization is not simply an accident of history but a systematic issue perpetuated by the dominant narrative in art criticism (Pollock). Despite the emergence of feminist art exhibitions and retrospective surveys dedicated to recovering women’s artistic achievements, such as Women Artists: 1550–1950 and Bauhaus Women: A Global Perspective, these efforts still struggle against the inertia of a canon built on masculine ideals. Recent analyses by the National Museum of Women in the Arts show incremental progress; yet, a significant gap remains in the mainstream presentation of women’s art.

The persistence of these stereotypes is also evident in contemporary art discourse. Even as digital media have provided platforms for independent artists to gain visibility, many female creators continue to be pigeonholed into categories defined by their gender rather than the quality of their work. As scholars like Frances Borzello argue, the ongoing reliance on biographical details to define women artists inadvertently reinforces the notion that their art is secondary to their personal stories. This duality, where women are both celebrated and trivialized, calls for a critical reappraisal of how female artists are represented in both academic and public spheres.

Formal art education has historically been a gatekeeper to professional success, yet its structures were fundamentally gendered. Elite institutions such as the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and early iterations of the Bauhaus have traditionally excluded women or confined them to subfields considered less rigorous. Despite a high number of female applicants, women were often systematically directed toward disciplines like weaving and pottery instead of painting or sculpture, which were deemed the domains of “true art” (Katsarova; Baumhoff). This restricted access to essential training, particularly life drawing and the study of the nude, that was crucial for mastering anatomy and developing a robust artistic vocabulary (Nochlin 22–39).

Additionally, the pedagogical methods employed in these institutions often reinforced prevailing gender stereotypes. Women in art academies frequently encountered curricula and critiques that emphasized modesty and delicacy over technical and conceptual innovation. Whitney Chadwick’s research indicates that these educational practices contributed to an internalized sense of inferiority among women artists, forcing them to work harder to gain recognition (Chadwick). Studies on art education have also shown that women who did gain entry into prestigious programs often had to forge alternative networks and mentorships outside of the traditional academic framework in order to overcome the limitations imposed on them (How Women Artists Navigate Communication and Creativity, 2023).

Additionally, economic constraints compounded these educational barriers. Many female artists, particularly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, had limited access to resources, scholarships, and financial support, which further hampered their ability to pursue long-term studies in the arts. In recent years, initiatives aimed at increasing funding and creating inclusive curricula have begun to address these disparities; however, the legacy of exclusion still affects the contemporary landscape, where women continue to earn less and receive fewer prestigious commissions than their male peers (Throsby et al. 167–190).

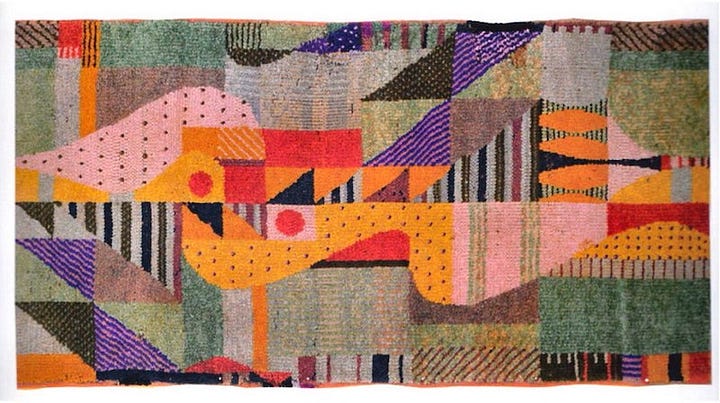

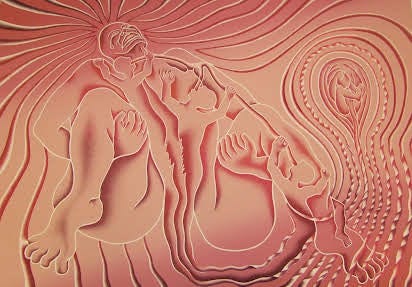

Despite systematic exclusion, women have made transformative contributions to nearly every art movement in history. In the modernist era, for instance, female artists at the Bauhaus, such as Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl, reinvented textile design, integrating techniques from painting and geometric abstraction to create works that redefined modern aesthetics (Otto and Rössler; Silane). Marianne Brandt’s pioneering work in the metal workshop challenged the gendered boundaries of industrial design, while Renaissance painters like Artemisia Gentileschi and Sofonisba Anguissola produced compelling works that questioned traditional depictions of power and femininity (Heller; Zoffany).

Moreover, feminist art movements of the 1970s catalyzed a broader reappraisal of women’s contributions. Artists such as Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, and Faith Ringgold used their work to confront and subvert patriarchal norms, infusing personal narrative and collective experience into their art (Chadwick; Pollock). Their efforts not only helped redefine what it meant to be a woman artist but also spurred institutional changes that began to challenge the male-dominated canon. Despite these advances, scholars such as Germaine Greer and Frances Borzello argue that many contributions remain undervalued due to persistent cultural biases that continue to glorify masculine creativity over collaborative and process-driven practices more typical of women (Borzello; Greer).

Recent economic studies have further highlighted these disparities. For example, analysis of gallery representation and auction sales reveals that female artists, even when successful, are often underrepresented and undervalued compared to their male counterparts (Throsby et al. 167–190). This enduring gap underscores the need for continued institutional reform and critical scholarship to fully integrate the achievements of women into the broader narrative of art history.

The digital age is providing new opportunities for female artists to overcome historical obstacles. Social media platforms, online galleries, and virtual exhibitions have democratized access to audiences and disrupted traditional gatekeeping in the art world. Recent research indicates that while women now constitute a majority of art school graduates, systemic issues, such as unequal funding, biased curatorial practices, and persistent pay gaps, continue to limit their professional visibility (National Museum of Women in the Arts 2019; Throsby et al. 2020).

Furthermore, intersectional approaches are increasingly informing feminist art criticism. Scholars like bell hooks and Audre Lorde have highlighted that issues of race, class, and cultural background compound the challenges faced by women artists, urging a more nuanced understanding of creativity that embraces diverse identities (Lorde; hooks). Initiatives such as the Countess Report and revised gender equity action plans at major institutions are practical steps toward addressing these imbalances. By collecting and analyzing data on gender representation in exhibitions and the art market, these initiatives aim to foster transparency and drive policy changes that benefit underrepresented artists.

Looking ahead, future research should focus on longitudinal studies that trace the evolution of women’s representation in both educational institutions and the art market. Additionally, comparative studies across different cultural contexts can illuminate how local traditions and systemic factors influence the visibility of female artists. By integrating perspectives from feminist aesthetics, cultural studies, and economic analysis, scholars can develop comprehensive strategies to dismantle the remnants of patriarchal bias in the art world and cultivate an environment in which all artists can thrive.

The historical exclusion and undervaluation of women artists is deeply rooted in entrenched gender roles and institutional biases that have persisted over centuries. Despite significant obstacles in formal education and professional recognition, women have continuously pushed the boundaries of art, transforming mediums and contributing to major movements from the Renaissance to modernism and beyond. Contemporary efforts, bolstered by digital platforms and intersectional scholarship, are gradually redressing these imbalances, yet systemic challenges remain. For a truly inclusive narrative of art history, it is imperative that future research, exhibitions, and institutional reforms continue to spotlight the achievements of women artists, ensuring that their contributions are fully acknowledged as central to the evolution of art.

References:

Abbey, Katharine. Identity Ambivalence in Women Artists. Journal of Feminist Studies, vol. 22, no. 3, 2004, pp. 145–160.

Baer, Jane, and Robert Kaufman. Creativity and Gender: New Perspectives. Creativity Research Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, 2008, pp. 73–85.

Baumhoff, Anja. The Gendered World of the Bauhaus: The Politics of Power at the Weimar Republic’s Premier Art Institute, 1919–1931. Peter Lang, 2001.

Borzello, Frances. Seeing Ourselves: Women’s Self-Portraits. Thames & Hudson, 2016.

Broude, Norma, and Mary D. Garrard. The Expanding Discourse of Art History: Women Artists. Art History, vol. 20, no. 4, 1997, pp. 471–490.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. 5th ed., Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Dodson, Aidan, and Salima Ikram. The Tomb in Ancient Egypt: Royal and Private. Thames & Hudson, 2008.

Feminist Art Project. Women and Art. National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2021, nmwa.org/advocate/get-facts.

Garrard, Mary D. Feminist Art and the Politics of Representation. Routledge, 1995.

Geoghegan, Laura. The New Woman of Bauhaus Scene: Reassessing Authorship. ProQuest, 6 Sept. 2023, http://hdl.handle.net/1961/thesesdissertations:544.

Gotthardt, Alexxa. The Women of the Bauhaus School. Artsy, 3 Apr. 2017, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-women-bauhaus-school.

Greer, Germaine. The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979.

Harker, Simon. Barriers in Art Education: A Comparative Study. Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 12, no. 3, 2018, pp. 203–220.

Heller, Nancy G. Women Artists: An Illustrated History. Abbeville Press, 1987.

Hooks, bell. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New Press, 1995.

Katsarova, Ivana. The Bauhaus Movement: Where Are the Women? European Parliamentary Research Service, Mar. 2021, www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/689355/EPRS_BRI(2021)689355_EN.pdf.

Lorde, Audre. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, 1984.

Moore, Suzanne. Who Does She Think She Is? The Challenge of Identifying Women Artists. The Independent, 4 Apr. 1998.

Nochlin, Linda. Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? ARTnews, Jan. 1971, pp. 22–39.

Otto, Elizabeth, and Patrick Rössler. Bauhaus Women: A Global Perspective. Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art. Routledge, 1988.

Silane, Sophia. The Women of the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop: Anni Albers’ and Gunta Stölzl’s Impact. Pitzer Senior Theses, Claremont Colleges, 2020, https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/114.

Throsby, David, et al. Gender in the Art Market: An Analysis of Gallery Representation. Journal of Cultural Economics, vol. 44, no. 2, 2020, pp. 167–190.

White, Hal, and John White. Gendered Perspectives in Art: The Case of the Nude. Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/n/nude. Accessed 17 Jan. 2025.

this why you're everything