Tamara de Lempicka (1898–1980) stands as a singular figure in the history of modern art, a painter whose work not only defined Art Deco aesthetics but also encapsulated the complexities of modern identity and gender. Her distinctive style, characterized by sleek lines, bold colors, and a synthesis of Cubist, Neoclassical, and Renaissance influences, continues to intrigue scholars and collectors.

Tamara de Lempicka emerged during an era defined by rapid technological change, social upheaval, and a redefinition of gender roles. Often hailed as the “Baroness with a Brush,” her portraits and nudes not only epitomize Art Deco’s luxurious modernity but also serve as visual commentaries on the emancipated woman of the early twentieth century. By blending influences as disparate as Cubism, Neoclassicism, and Renaissance art, de Lempicka created a style that resonated with both the avant-garde and high society. This paper examines her multifaceted career and situates her work within broader cultural, social, and artistic contexts.

De Lempicka’s biographical record is complex and sometimes contradictory. Born, according to her own account, in 1898 in Warsaw, she was raised in a culturally affluent milieu. Her father, a Russian Jewish attorney, and her mother, from an established Polish family, provided her with early exposure to European high culture and the visual arts (Britannica). Educated partly in Lausanne and later immersed in the artistic atmosphere of St. Petersburg, she encountered the works of Renaissance masters during a formative trip to Italy in 1911. These early experiences not only fostered her aesthetic sensibilities but also instilled in her the desire to reinvent herself; a theme that would pervade her later career (Claridge).

The tumult of the Russian Revolution disrupted her early married life with Tadeusz Łempicki, a young lawyer she wed in 1916. Faced with political and personal upheaval, de Lempicka fled to Paris, a city that promised both refuge and artistic reinvention. In Paris, she rebranded herself by appending “de” to her surname, thereby evoking aristocratic allure and distancing herself from her uncertain origins (Blondel).

In Paris, de Lempicka pursued formal art education at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the Académie Ranson. Her early studies under Maurice Denis instilled in her a rigorous approach to draftsmanship and color harmonies, while her later instruction with André Lhote introduced her to a refined, “soft” Cubism that allowed her to maintain naturalistic forms while experimenting with geometric abstraction (Blondel; Claridge).

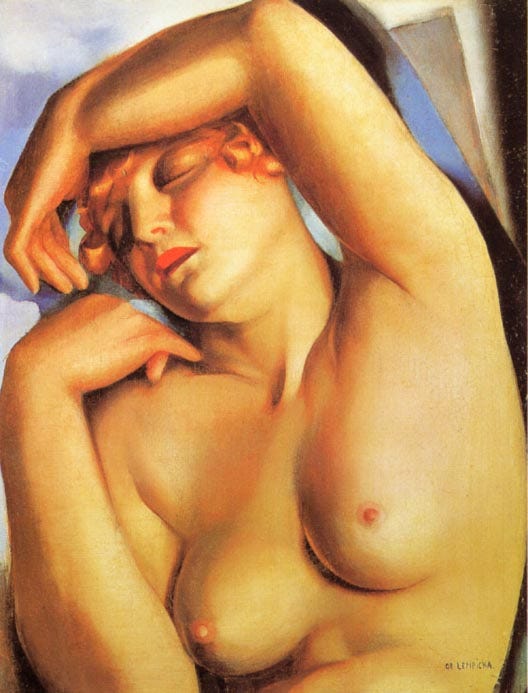

Her evolution was marked by an energetic synthesis of past and present: she absorbed the fluid sensuality of Renaissance and Mannerist art, drawing inspiration from artists such as Ingres and Bronzino, and merged these classical elements with the angular forms and vibrant palette of Cubism and Art Deco (Néret). This fusion created a signature style defined by crisp, metallic surfaces and bold, streamlined compositions, which later became synonymous with the modernity of the interwar period.

Art Deco emerged in the 1920s as an expression of luxury, progress, and technological optimism. Its emphasis on symmetry, geometric patterns, and sleek materials resonated with a society in the midst of rapid industrialization and cultural change (Arwas). De Lempicka’s work is often cited as the visual embodiment of Art Deco painting. Her compositions, characterized by clear, luminous color fields and strong, simplified forms, reflect the era’s desire for both refinement and dynamism (Britannica).

One of her most celebrated works, Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti) (1929), exemplifies this aesthetic. The painting portrays de Lempicka at the wheel of a luxury car, symbolizing independence and modernity. The juxtaposition of the sleek vehicle with her elegant, almost statuesque form articulates the newfound autonomy of women during the Jazz Age (Claridge; Birnbaum).

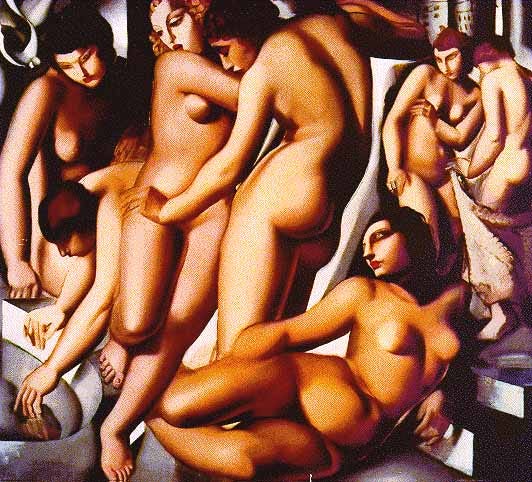

De Lempicka’s oeuvre spans portraits of high society, provocative nudes, and self-portraits that articulate her personal mythology. Works such as The Dream (1927) and The Musician (1929) reveal her ability to balance figurative clarity with abstracted, geometric forms. Her repeated portrayals of her daughter, Kizette, imbue her work with an intimate dimension, while her erotic nudes challenge conventional portrayals of the female body (Birnbaum).

Themes of sexual liberation, gender fluidity, and the celebration of the modern individual recur throughout her work. De Lempicka’s technique, marked by smooth, enameled surfaces, precise brushwork, and a controlled use of light, creates images that are both sumptuous and rigorous. Her innovative application of color and form not only redefined portraiture but also offered a visual language for articulating the complexities of modern identity (Néret; Aldrich and Wotherspoon).

De Lempicka’s personal narrative is intertwined with her public persona. Openly bisexual and unafraid to challenge social norms, she navigated the male-dominated art world by subverting expectations. Early in her career, she even signed her works with a masculine variant of her surname to gain credibility; a decision that reflects the gender politics of her time (Aldrich and Wotherspoon).

Her tumultuous relationships, including her divorce from Tadeusz Łempicki and later marriage to Baron Raoul Kuffner, not only influenced her subject matter but also reinforced the themes of reinvention and self-determination that define her work. The interplay between her personal freedom and public success is evident in the confident, autonomous figures she portrayed; figures that continue to inspire discussions of modern femininity and queer aesthetics (Mackrell).

By the late 1930s, with the onset of World War II and the advent of new artistic movements such as Abstract Expressionism, de Lempicka’s figurative style fell out of favor. After relocating to the United States and eventually to Mexico, her output diminished as the art world’s tastes shifted. However, retrospective exhibitions in the 1970s, notably at the Musée du Luxembourg, reawakened scholarly and collector interest in her work (Néret).

Today, de Lempicka’s paintings command high prices at auction and continue to influence contemporary aesthetics. Her legacy is reinforced by the high-profile collections of celebrities like Madonna and by ongoing academic reassessments that position her as a pioneering figure in both art history and feminist discourse (Claridge; Birnbaum).

Tamara de Lempicka’s contributions to Art Deco are not confined to her distinctive visual style; they also extend to her role as a cultural icon. She redefined the possibilities for female self-representation and challenged the artistic conventions of her time. As a woman who continually reinvented her identity, both through her art and her personal life, de Lempicka has come to symbolize the liberated modern woman (Britannica).

Her influence persists in popular culture and in the art market. Exhibitions and retrospectives regularly celebrate her innovative spirit, while scholarly discourse increasingly recognizes her work as a critical bridge between traditional academic art and the radical modernity of the 20th century. De Lempicka’s ability to merge high art with commercial appeal continues to prompt discussions about the intersections of aesthetics, gender, and consumer culture (Mackrell; Aldrich and Wotherspoon).

Tamara de Lempicka’s career is a testament to artistic reinvention and the transformative power of the Art Deco movement. Through a unique synthesis of classical influences and modernist techniques, she not only defined a visual language for an era but also challenged traditional representations of gender and identity. Her life, marked by dramatic migrations, personal upheavals, and a fearless embrace of her sexuality, remains an enduring inspiration for contemporary discussions of art, modernity, and the role of women in the creative sphere. De Lempicka’s work, ever reflective of a complex cultural moment, continues to captivate both the scholarly world and a broader public fascinated by her bold celebration of modern life.

References:

Aldrich, Robert, and Garry Wotherspoon, editors. Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History from Antiquity to World War II. Routledge, 2002.

Birnbaum, Paula J. Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities. Ashgate, 2011.

Blondel, Alain. Tamara de Lempicka: Catalogue Raisonné 1921–1979. Royal Academy Books, 2004.

Claridge, Laura. Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence. Clarkson Potter, 1999.

Mackrell, Judith. Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation. Pan Books, 2013.

Néret, Gilles. Tamara de Lempicka: 1898–1980, déesse de l'ère automobile. Taschen, 2016.

Tamara de Lempicka. Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/biography/Tamara-de-Lempicka. Accessed 18 Jan. 2025.

I do really like that style of painting, I knew an artist whose style was similar to that, and cited Lempicka as an influence

In many ways, Lempicka is and was the bridge we needed from cubism and futurism to what became more fashionable and stylized for public consumption. An interesting set of essays would be a sort of

This + This = THIS formula of which this one is obvious but many others are less so.

There is a set of characteristics that was (and to a degree still is) necessary and consistent for women of Euro-Eastern Block countries to reinvent, play roles and adapt to an environment of instability and unpredictability they were/are born to that western women could take some lessons from. It’s a mix of migrational/cross-cultural absorption and reinterpretation for survival: Being/becoming a shiny object with brains and sensuality resulting in an ultimate form of creative thinking and in some cases—incredibly groundbreaking ART.

Another paper worth delving into… my, my. We are dangerous.