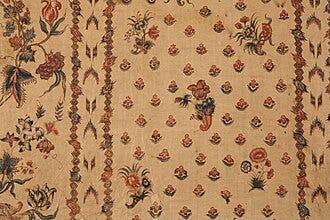

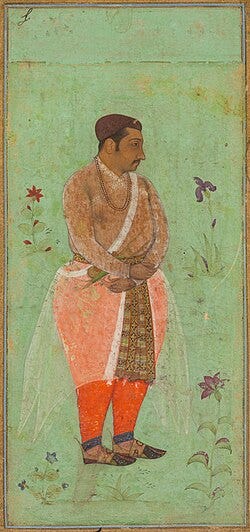

Mughal emperors clothed themselves in the finest fabrics to manifest imperial glory. The court’s wardrobes featured ultra-fine muslins (especially Bengal cottons) prized for their softness and coolness as much as for luxury. Sumptuous brocades woven with silk and metal threads signaled wealth: gold- and silver-brocaded textiles often adorned royal garments and diplomatic gifts. Indeed, silk and gold-woven cloth “circulated between geographically and religiously distinct courtly spaces,” forming a shared luxury culture. European and Central Asian imports supplemented local weaving: the Mughals collected rare silks from Iran, Turkey, Europe, and the Far East. These fabrics typically bore dense floral and arabesque patterns, reflecting Mughal aesthetic tastes and cross-cultural influences. The extreme fineness of muslin and the ornate relief of brocade epitomized Mughal sartorial craftsmanship and reinforced the court’s status.

Beyond textiles, Mughal opulence showed in precious metalwork and jewels. The imperial treasury abounded in gem-studded objects – swords, daggers, and ornamental vessels – often serving as regalia or state gifts. Exhibitions note that Mughal artisans mastered kundan gem-setting (pure gold foil around stones) and carved hardstones like jade and crystal. A dagger handle is carved from jade and inlaid with flush-mounted rubies is a classic Mughal combination. The Mughal “jeweled dagger” tradition included hilts of pure gold encrusted with thousands of diamonds, rubies, and emeralds, literally proclaiming imperial wealth. Metal vessels and weapon fittings were hammered in relief (gilded or damascened), and richly enameled in vivid colors. As one curator observes, the Mughal court’s reputation for wealth and artistry was “epitomized in the jeweled arts,” which circulated lavishly at court. In sum, Mughal metal and jewelry work combined sophisticated techniques (inlay, enameling, carving) with precious materials to serve as visible symbols of status and technical prowess.

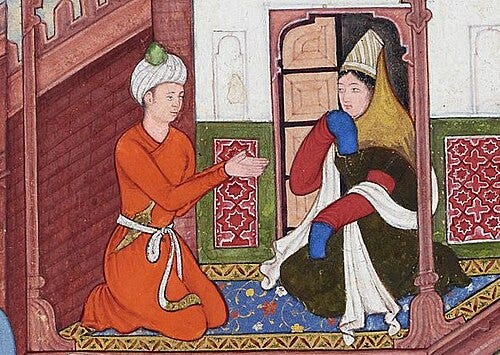

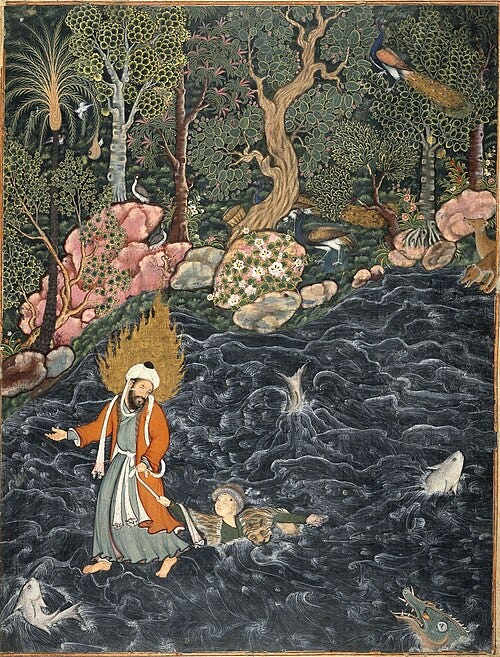

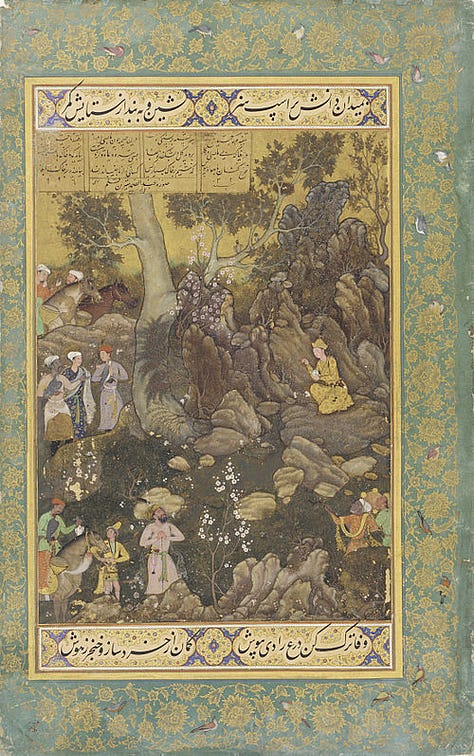

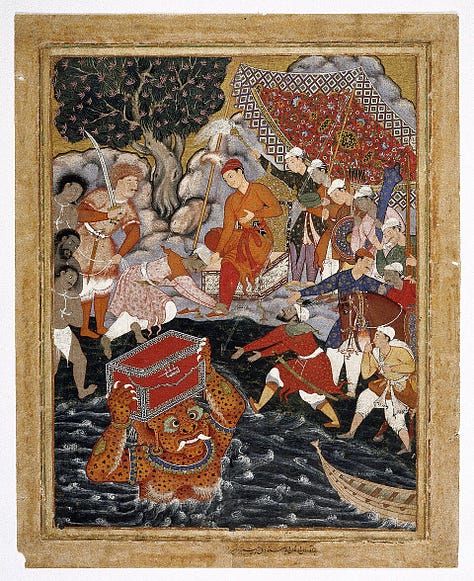

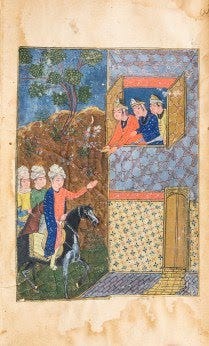

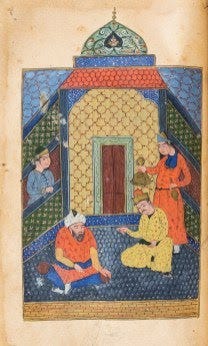

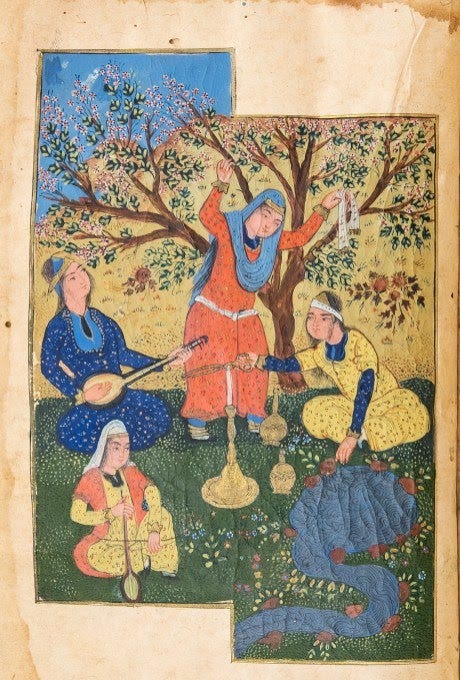

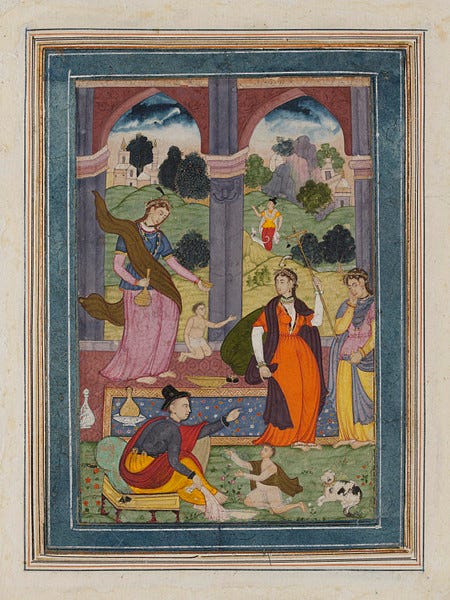

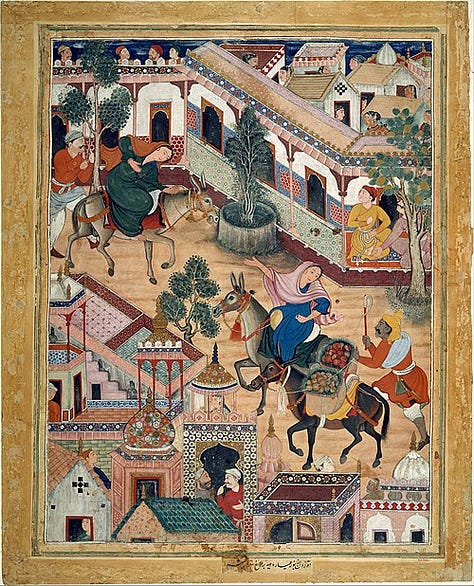

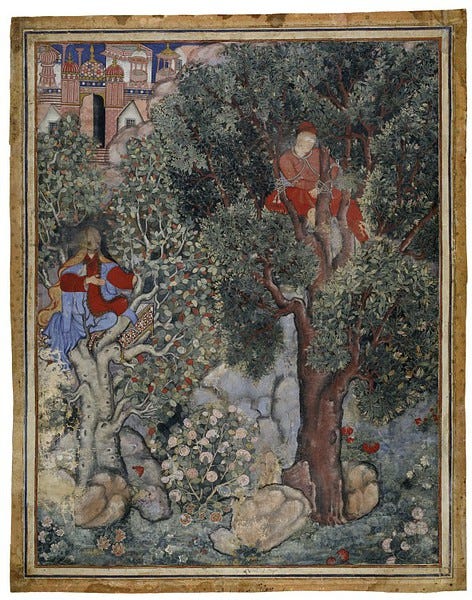

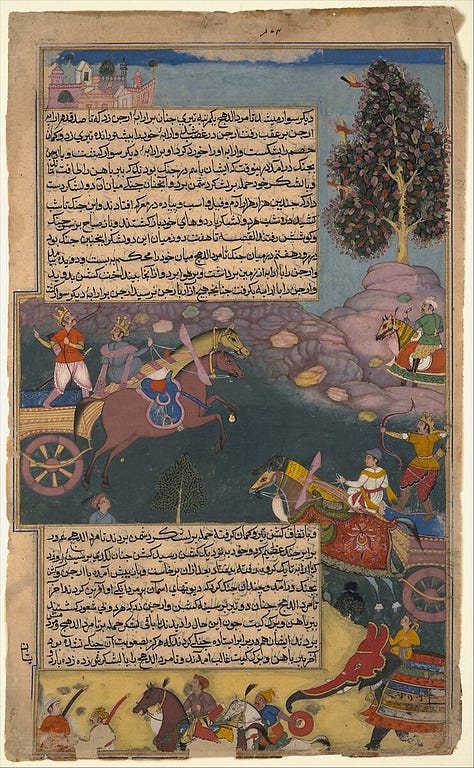

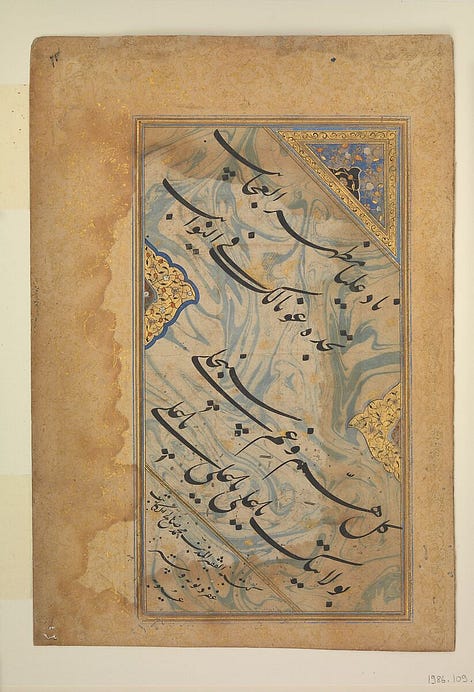

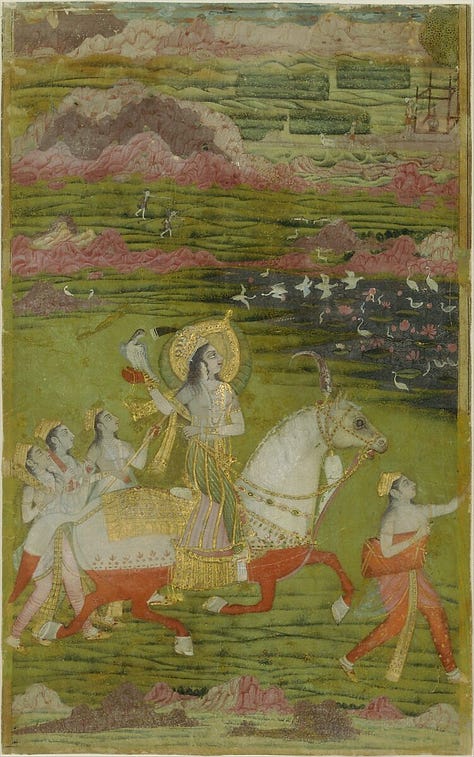

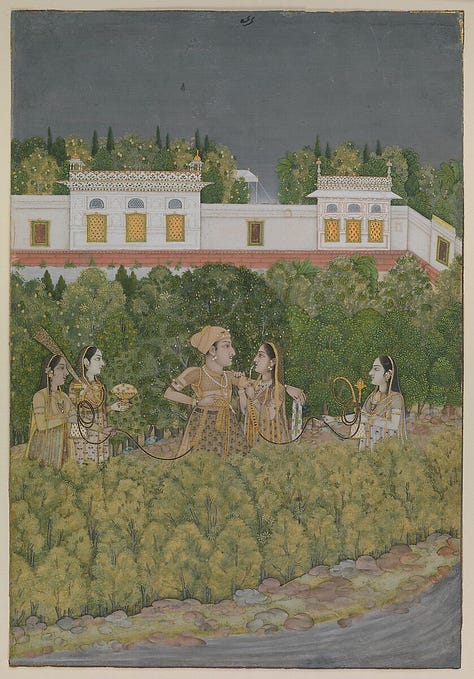

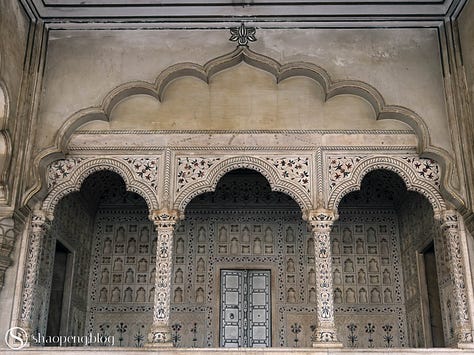

From its inception, Mughal style was deeply rooted in Persian and Central Asian precedent. The first emperor, Babur, consciously modeled his estates on the Timurid (Iranian) tradition; he “constructed new buildings and laid out gardens in the geometric Iranian style” (e.g. charbagh quadrilateral gardens). This Persian garden aesthetic, with water channels and symmetric flower beds, became a signature of Mughal palaces (e.g. Humayun’s Tomb, Shalimar Gardens). In painting, the influence was direct. Akbar’s court employed Iranian master painters (like Mir Sayyid ‘Ali and ‘Abd al‑Ṣamad), who brought fine brushwork, saturated color, and Persian compositional formats. Mughal miniatures inherited vertical formats, high viewpoints, and intricate ornamentation from Safavid art, while blending in Indian naturalism. Even Mughal royal iconography (halos, idyllic paradisiacal scenery) echoed Persian court imagery. In architecture, Perso-Islamic motifs were ubiquitous: mosques and mausolea featured the pishtaq arch, bulbous domes, and glazed tile revetments. Under Shah Jahan, lavish polychrome tile decoration – with floral motifs and Persian inscriptions – adorned garden pavilions and gateways in Lahore and Kashmir. Thus Mughal art and gardens represent a syncretic Indo-Persian aesthetic, inheriting Iranian forms (from script to garden layout) and adapting them to India’s local materials and craftsmanship.

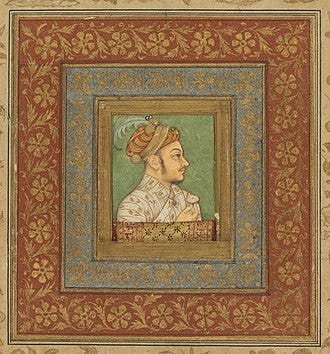

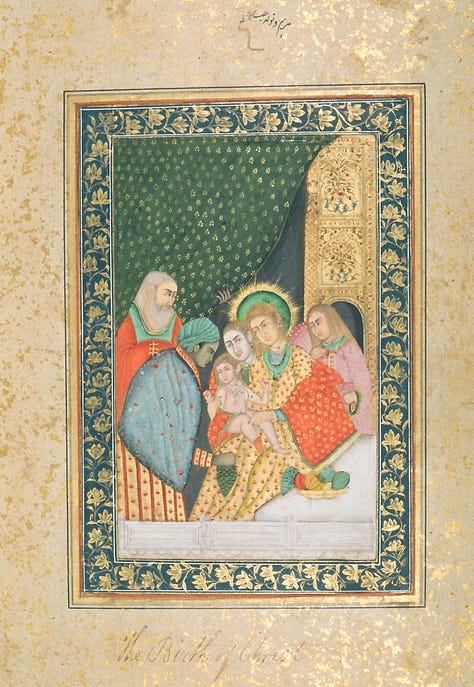

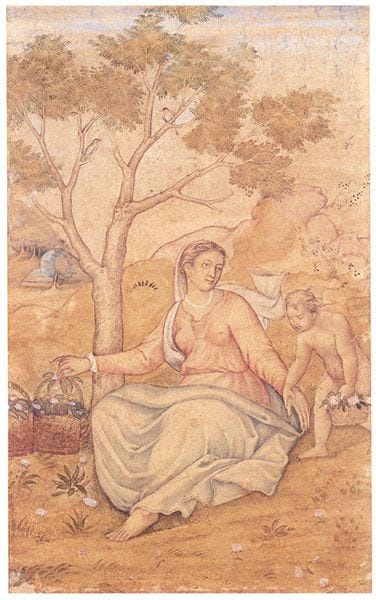

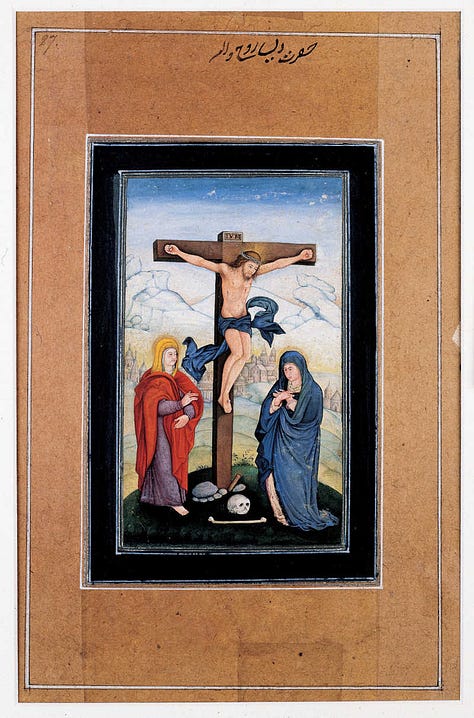

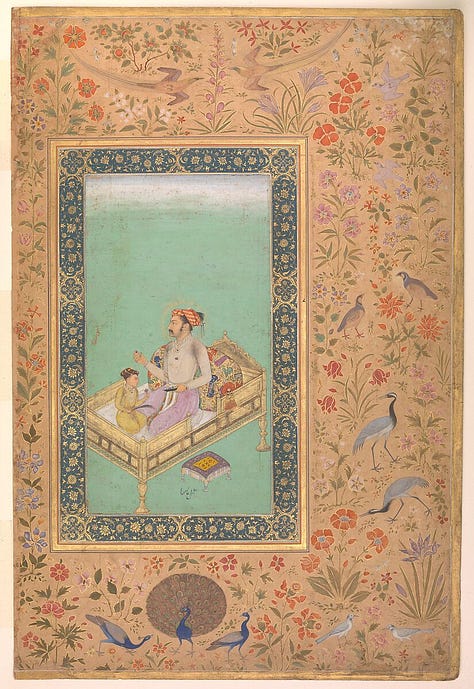

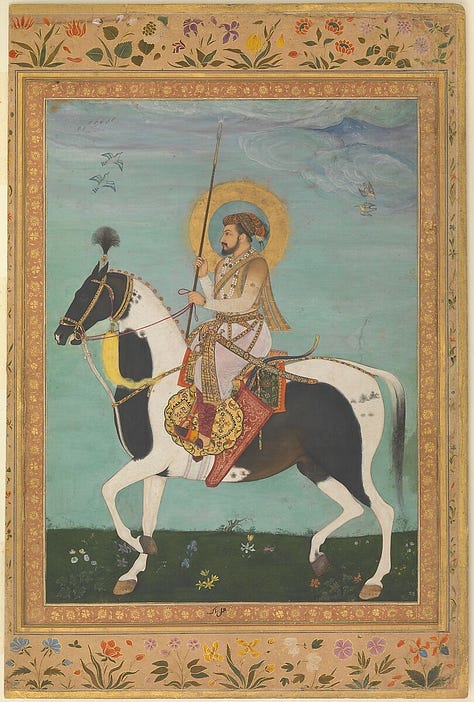

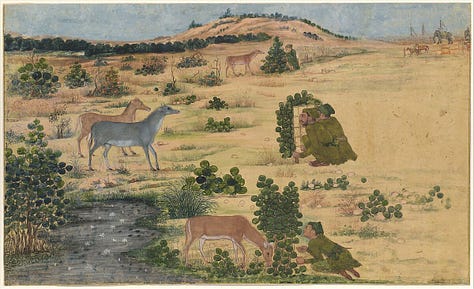

Jahangir’s reign saw European imagery and techniques enter Mughal art through trade and missionary contacts. The emperor avidly collected Western oil paintings and prints, exposing his atelier to Renaissance conventions. He explicitly encouraged his court painters to adopt chiaroscuro (light-and-shade modeling) and linear perspective. Indeed, scholars note that Jahangir “supported artists who mastered the techniques of European chiaroscuro and perspective,” blending these into Mughal illumination. The result was more naturalistic portraiture and three-dimensional space than in earlier Mughal work. One sees this in Jahangir’s own posthumous portraits and in studies of animals and plants, which display Western-style shading. Christian iconography also briefly appeared, for instance, Mughal miniatures of Biblical scenes, though integrated subtly. In sum, European influence under Jahangir enriched Mughal painting’s realism and depth without supplanting its core Persianate style.

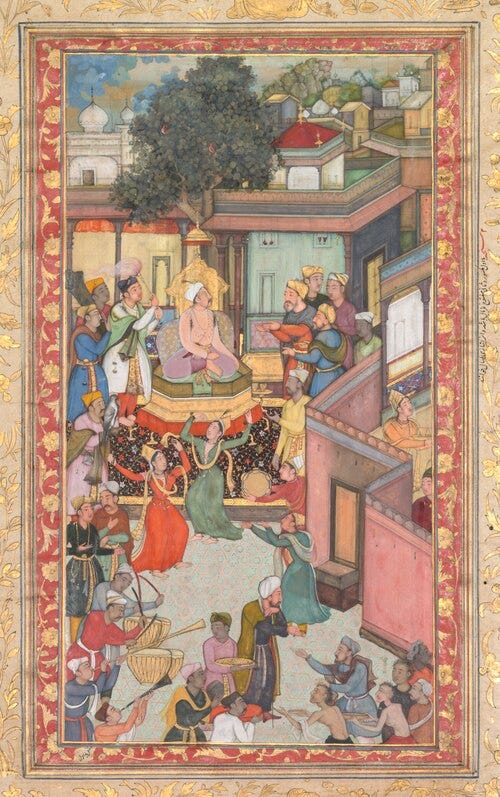

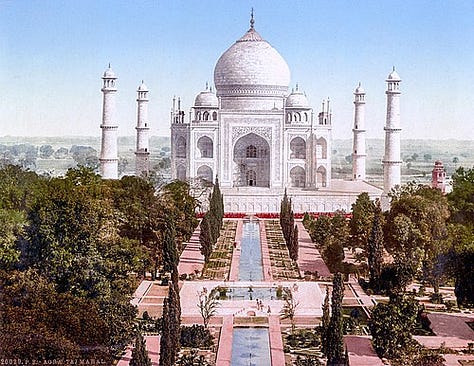

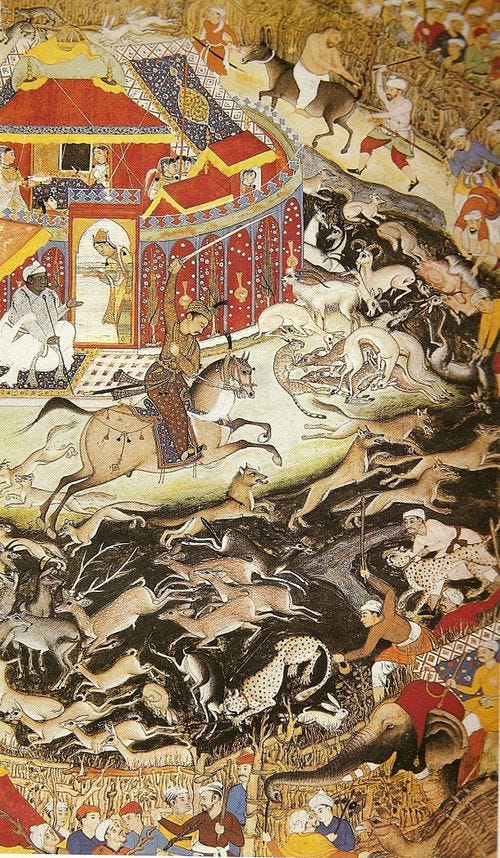

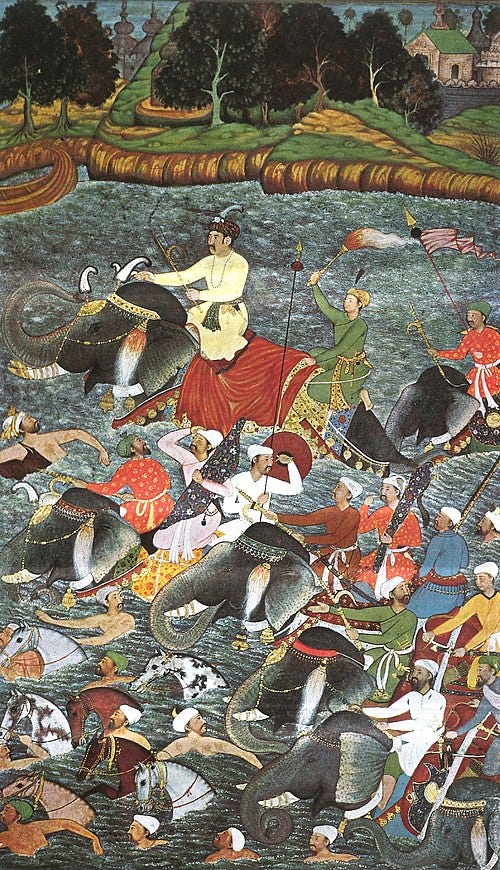

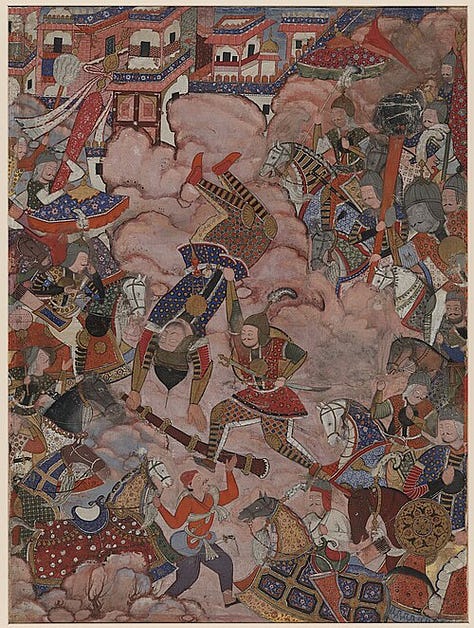

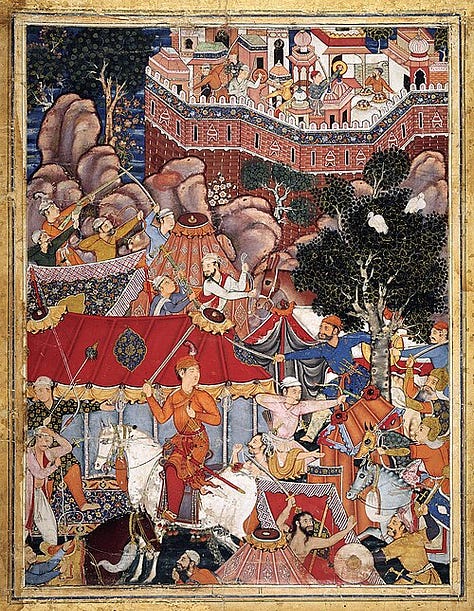

Imperial patronage was central to Mughal art’s flourishing. Emperors and high nobles did not merely buy art, they became its directors and visionaries. As one study argues, Mughal rulers “understood the aesthetic as a crucial element of governance,” using art to assert power and project an imperial identity. Akbar (r. 1556–1605) spearheaded a systematic policy: he gathered Hindu and Muslim craftsmen alike into royal karkhanas and commissioned monumental manuscripts and palaces. Under Akbar’s guidance, thousands of artisans illustrated the Akbar-nama and Hamzanama, blending indigenous and Persian elements into a new Mughal idiom. Jahangir (r. 1605–27) continued this by favoring naturalism, personally reviewing portraits and botanical paintings and sanctioning the use of European techniques. Shah Jahan (r. 1628–58) then poured enormous resources into architecture and decorative arts: his projects (the Taj Mahal, Lahore Fort, etc.) employed advanced pietra dura inlay, carved marble screens, and resplendent textiles to realize an idealized imperial vision. Crucially, Mughal patrons actively supervised creation: they “reviewed sketches, selecting materials, and issuing directives” in the workshop. Through this hands-on sponsorship, rulers ensured that every stroke of the brush or chisel reinforced Mughal grandeur and innovation.

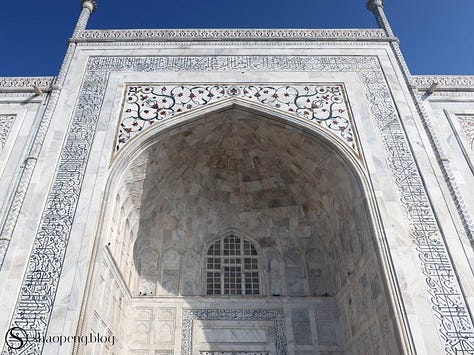

Mughal artisans employed sumptuous materials and sophisticated techniques in all media. The most famous example is the marble inlay work of Shah Jahan’s era; pure white Makrana marble was carved and inlaid with colored pietra dura stones to form floral arabesques and calligraphy. One can see black marble letters and flower patterns flush with the Taj Mahal’s façade. Beyond marble, craftsmen carved jade and crystal into vessels and decorative boxes, often mounting them with gems, Mughal courts prized Chinese jade and Central Asian nephrite for this purpose. In metalwork, techniques flourished; precious alloys were chased and damascened with gold, and the famed kundan setting surrounded gems with thin gold foil. Enamel decoration added brilliant polychromy to metal and porcelain pieces. In painting and book art, artists used finely ground opaque pigments (watercolors) with gold leaf on burnished cotton or paper. Wood and leather carving (jalis, book covers) employed intricate geometric and floral motifs. In textiles, Mughal weavers perfected tie-dye (bandhani) and elaborate brocade with gold threads. Taken together, this mastery of diverse materials – marble, precious stones, metals, pigments, and textiles, allowed Mughal decorative art to achieve unprecedented elegance. The legacy is global: even today designs inspired by Mughal inlay, calligraphy and floral patterns appear in architecture and crafts worldwide.

The Mughal imperial workshops produced several masterful artists and architects. In painting, ‘Abd al‑Ṣamad (b. Shiraz, mid-16th c.) was a towering figure; he served Humayun and Akbar and essentially trained a generation of painters. He co-directed the royal atelier and “was personal tutor to the young Akbar”. Under Abd al‑Ṣamad’s leadership, the huge Hamzanama (legends of Amir Hamza) project was completed: ten volumes, over a thousand large miniatures that blended Indian and Persian styles into the new Mughal manner. This fusion defined Mughal painting. Later, artists like Abu’l-Hasan (Jahangir’s favorite) and Bichitr (Shah Jahan’s court painter) achieved fame for their refined royal portraits. In architecture, the chief names include Ustad Ahmad Lahauri, the principal architect of the Taj Mahal, and Inayat Khan (designer of the Taj’s gardens). Lahauri in particular rose to high esteem: as one scholar notes, “Ustad Ahmad Lahauri, believed to be the chief architect of the Taj Mahal, earned royal recognition” for his design genius. These figures illustrate that Mughal artistic excellence was not anonymous. Master painters and architects became legendary at court, blending the diverse influences of the empire into enduring masterpieces.

Mughal arts peaked under Shah Jahan and then waned under Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), whose wars and austerity drained the treasury. By the end of Aurangzeb’s reign the empire was at its largest extent but greatly impoverished; after 1707 it fragmented into regional states. Successor courts in Delhi, Awadh, and provincial capitals did continue Mughal artistic conventions, but on a reduced scale. None could match the imperial workshops’ earlier lavishness. Nonetheless, the aesthetic legacy was profound. “The Mughal Empire is remembered for its visual grandeur; majestic architecture, exquisite paintings, luxurious textiles, and ornate jewelry”. Mughal motifs and techniques survived in Rajput, Sikh, and Deccani art. In the colonial period, Indo-Saracenic architecture explicitly revived Mughal arches and domes. Today Mughal-era art draws global admiration: UNESCO sites like the Taj Mahal are iconic, and contemporary Indian textiles and jewelry still echo Mughal designs. While the Mughal state ended, its fusion of Persian, Central Asian, and Indian art continues to influence culture in South Asia and beyond.

Mughal art represented both continuity and innovation relative to earlier Indian traditions. Pre-Mughal North Indian painting (e.g. Sultanate manuscript illumination, Rajput miniature art) was typically devotional or courtly in a more localized idiom. Akbar’s workshops deliberately merged these indigenous elements with imported styles: as one historian notes, Akbar “welcomed Hindu and Muslim artisans alike, blending indigenous and Persian influences into a distinct Mughal idiom”. Thus Mughal miniatures, while secular and naturalistic, incorporated narrative motifs from local folklore as well as formal devices from Persia. Likewise, Mughal architecture added Persian and Timurid forms (charbagh gardens, bulbous domes, iwans) to the subcontinent’s repertoire. Earlier Hindu temple and sultanate architecture had different forms (shikharas, corbelled arches). Yet the Mughal style did not erase its context: artisans still used local materials (sandstone, marble) and flower motifs echoing native art. In summary, Mughal arts can be seen as a synthesis: they introduced new elements (European perspective, Persian gardens) into a South Asian framework, creating innovations that stood out from but also respectfully built upon India’s artistic heritage.

References:

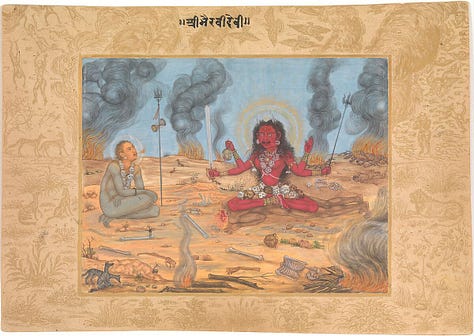

Abd al‑Ṣamad. Akbar and a Dervish. ca. 1580–90, opaque watercolor on paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Houghteling, Sylvia. The Emperor’s Humble Clothes: Textures of Courtly Dress in Seventeenth-Century South Asia. Ars Orientalis, vol. 33, 2003, pp. 90–111.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Treasury of the World: Jeweled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals. Exhibition overview, 2001, www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2001/jeweled-arts-of-mughal-india.

Sah, Archana Kumari. The Art of Empire: A Critical Analysis of Mughal Artisans and Their Cultural Legacy. International Journal of History, vol. 6, no. 1C, Jan. 2024, pp. 188–197, doi:10.22271/27069109.2024.v6.i1c.449.

Sardar, Marika. Indian Textiles: Trade and Production. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct. 2003, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/intx/hd_intx.htm.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Fragment of a Textile (India, Mughal Empire, mid-17th century). VMFA Collections, vmfa.museum/explore/collection/object/textile-68-8-156/.

Victoria and Albert Museum. The Arts of the Mughal Empire. V&A Museum Collections, www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-arts-of-the-mughal-empire.