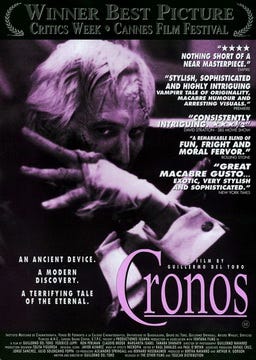

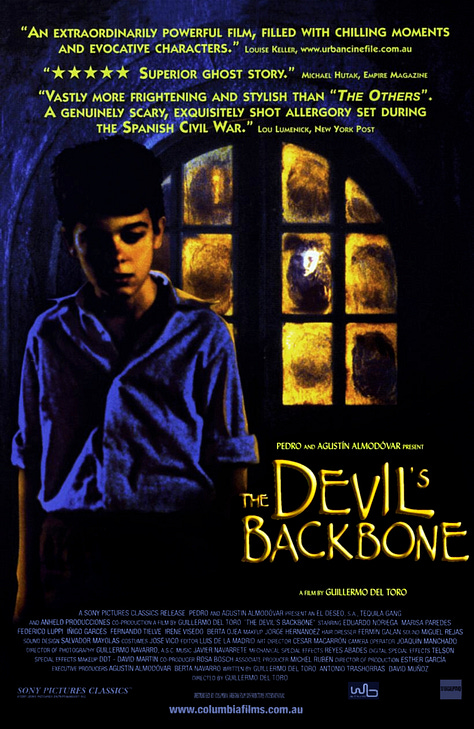

Guillermo del Toro Gómez, born October 9, 1964, in Guadalajara, Mexico, is a filmmaker, author, and artist whose career spans nearly four decades. Raised in a strict Catholic household, he began experimenting with his father’s Super 8 camera at age eight, crafting early shorts that married macabre humor with DIY effects; a foreshadowing of his later work in practical creature design (Britannica)(IMDb). His feature debut, Cronos (1993), emerged after the loss of his original stop-motion project, Omnivore, to vandalism; an early lesson in creative resilience that would shape his commitment to physical effects and hand-crafted monsters (Britannica; Turner 2018). From Spanish-language fables like The Devil’s Backbone (2001) to English-language blockbusters such as Hellboy (2004) and the Oscar-winning The Shape of Water (2017), del Toro’s films are unified by a deep reverence for folklore, Gothic myth, and the tactile beauty of the grotesque (Britannica).

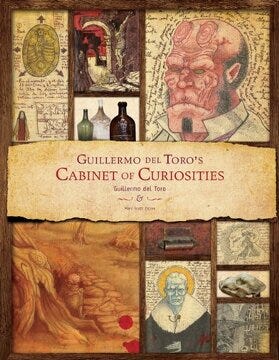

Del Toro often describes his monsters as “saints” within a personal mythology, insisting they be conceived with the same reverence afforded religious icons. In Cabinet of Curiosities: My Notebooks, Collections, and Other Obsessions (2013), he writes, “My monsters need to look entirely possible in their impossibility,” underscoring his drive to render creatures believable from any angle (lacma.org). Ann Davies situates del Toro’s monsters within the framework of “matter out of place,” arguing that their power arises from defying normalcy in ways that both attract and repel, reinforcing their status as metaphors for societal fears and taboos (link.springer.com). This sacred-object approach ensures each creature embodies emotional truth and narrative weight, transforming sketches into relics that carry mythic resonance.

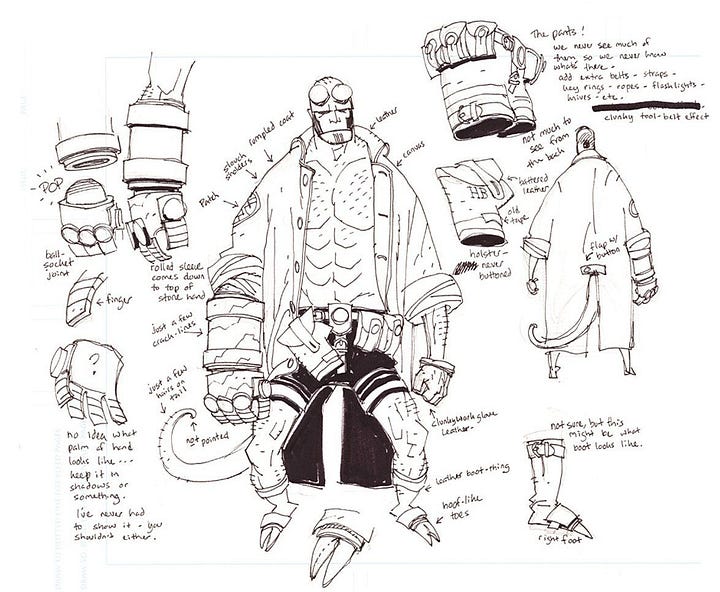

Del Toro’s creative process is anchored in voluminous notebooks, akin to da Vinci’s codices, where pencil sketches intertwine with prose and biomechanical notes. An Open Culture gallery of his notebooks shows early drawings for Pan’s Labyrinth, Hellboy, and Pacific Rim, replete with anatomical annotations and texture studies that guide sculptors and visual effects teams (openculture.com). Beyond two-dimensional renderings, he collaborates with artists like Guy Davis on Pinocchio (2022), whose stop-motion concept art fuses Marine biology with puppetry, producing hybrid figures that oscillate between whimsy and dread (Screen Rant). These sketches are not mere blueprints but narrative engines; each line suggesting backstory, motion, and psychological subtext.

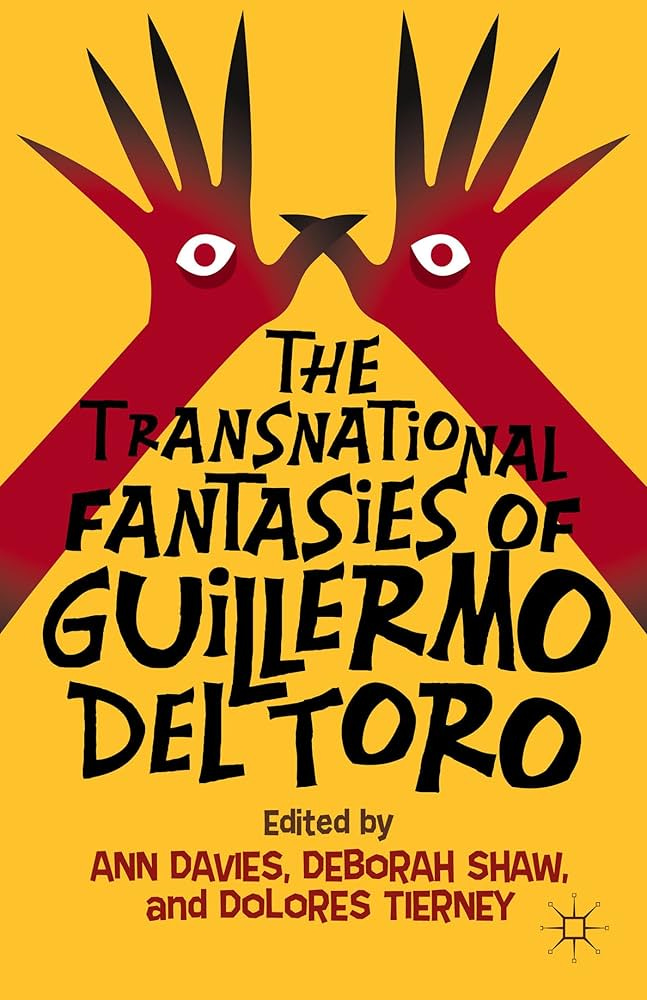

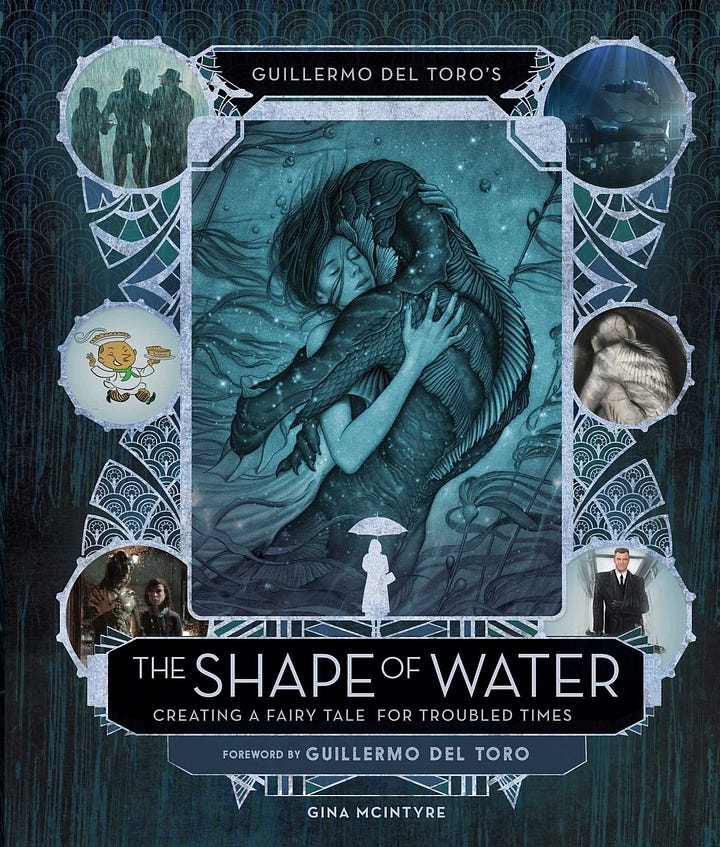

Scholars have traced del Toro’s monsters to mythic and psychoanalytic traditions in which “otherness” becomes a lens for examining cultural anxieties. In The Transnational Fantasies of Guillermo del Toro, Davies et al. contend that del Toro’s creatures, whether the Pale Man or the amphibian in The Shape of Water, operate as liminal figures, exposing the abject undercurrents of innocence, desire, and repression (iafor.org). A recent IAFOR study on The Shape of Water reads the amphibian-human hybrid as a “metaphorical device for investigating issues involving power, agency, and the boundaries that define what is human,” revealing del Toro’s subtle insertion of queer subtext and critiques of institutional violence (en.wikipedia.org). Through these lenses, his monsters are catalysts for empathy rather than fear alone.

In Pan’s Labyrinth, del Toro’s sketches of the Faun and Pale Man blend fairy-tale grace with visceral horror. Early concept pages published in Sketches by Guillermo del Toro, display multi-angle studies of the Pale Man’s sagging flesh and predatory gait, ensuring that he reads as both dream and nightmare (openculture.com). The film’s production art, later exhibited in At Home with Monsters, reveals how del Toro’s layered pencil and ink drawings informed Guillermo Navarro’s haunting cinematography, uniting grotesque form with poetic melancholy (britannica.com).

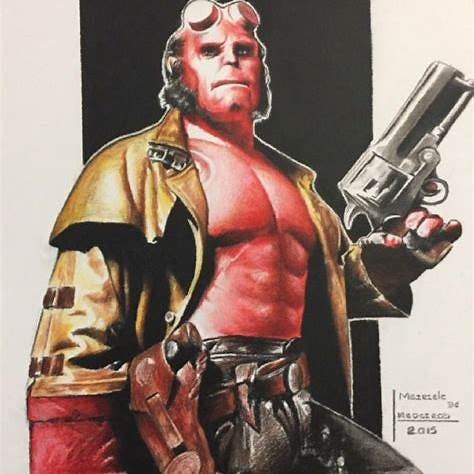

For Hellboy and Hellboy II: The Golden Army, del Toro worked closely with concept artists Mike Mignola and Arthur Max, generating a bestiary of demon-insect hybrids. In Show the Monster, del Toro recounts designing “tooth fairies” whose oak-leaf wings concealed blinking eyes; an inversion of childhood icons that underscores his devotion to detail and emotional authenticity (newyorker.com). These concept sketches, published alongside interviews in The Observer, guided practical effects by Legacy Effects, ensuring that each creature could exist as a physical puppet on set (iafor.org).

Over three years, del Toro refined his amphibian man through clay maquettes and water-colour studies, seeking a balance of alien otherness and human vulnerability. The IAFOR article on The Shape of Water highlights how his iterative sculpting sessions produced a creature whose “humanization of the monstrous” serves as a counterpoint to the film’s moral monsters, embodied by Michael Shannon’s Colonel Strickland (iafor.org). Del Toro’s own reflections in Cabinet of Curiosities reveal how he adjusted fin placement and eye-stalk curvature to elicit empathy from both actors and audiences (lacma.org).

In his stop-motion Pinocchio, del Toro partnered with Guy Davis to conceive hybrid puppets that echo Collodi’s moral fable while retaining his Gothic sensibilities. Davis’s concept art, circulated on Tumblr, portrays Count Volpe’s carnival specters, grotesque amalgams of rodent and human, that supplement Geppetto’s handcrafted puppet in the film’s afterlife sequences (Gebo4482). Del Toro’s remarks in IndieWire emphasize his return to animation’s tactile roots, asserting that “animation is much more my speed” and allowing him full control over monster performance and nuance (IndieWire).

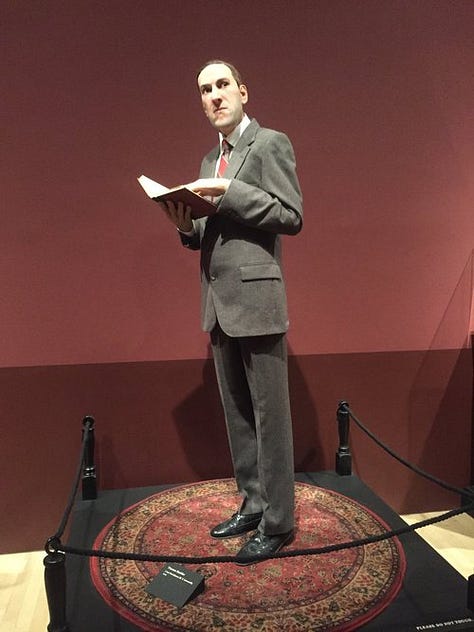

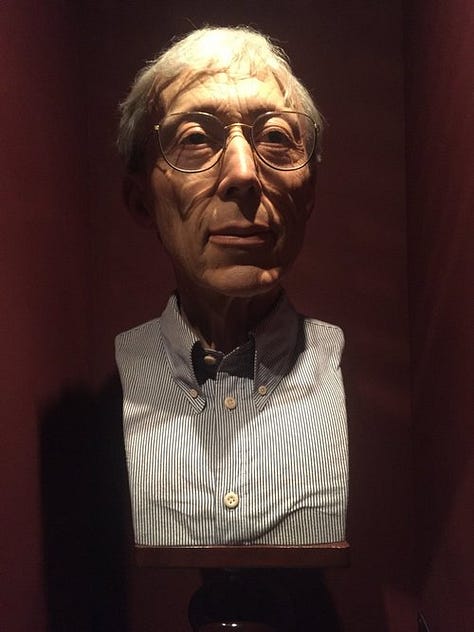

Del Toro’s concept art has been curated in major exhibitions, most notably Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters at LACMA and the Art Gallery of Ontario, where visitors view original notebooks, maquettes, and storyboards displayed alongside commentary on his process (lacma.org). The accompanying 256-page volume, Cabinet of Curiosities, assembles over 300 images of sketches, models, and personal artifacts, positioning his notebooks as standalone art objects that document the interplay between creature design and cinematic storytelling (openculture.com).

Guillermo del Toro’s oeuvre demonstrates that monsters are not mere genre tropes but conduits for myth, memory, and moral inquiry. His meticulous concept art practices, rooted in hand-drawn notebooks, clay sculpting, and collaborative model-making, ensure that each creature carries narrative weight and emotional authenticity. Through scholarly lenses of “matter out of place” and abjection, his monsters emerge as sympathetic outsiders, challenging viewers to confront the line between humanity and otherness. Del Toro’s legacy affirms that the true power of cinema lies not in spectacle alone, but in the alchemy of imagination, craft, and empathy.

References:

Del Toro, Guillermo. Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Guillermo-del-Toro. (britannica.com)

Guillermo del Toro. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, March 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guillermo_del_Toro. (en.wikipedia.org)

del Toro, Guillermo, and Marc Scott. Cabinet of Curiosities: My Notebooks, Collections, and Other Obsessions. HarperCollins, 2013. (lacma.org)

Davies, Ann, et al., editors. The Transnational Fantasies of Guillermo del Toro. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. (link.springer.com)

Sketches by Guillermo del Toro Take You Inside the Director’s Wildly Creative Imagination. Open Culture, 10 Mar. 2014, https://www.openculture.com/2014/03/frightening-sketches-by-guillermo-del-toro.html. (openculture.com)

What Do We Fear? Trauma, Past and the Monster: Perspectives on Works of Murnau and Guillermo del Toro. ResearchGate, Jan. 2014, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283642708_What_do_we_fear_Trauma_Past_and_the_Monster_Perspectives_on_works_of_Murnau_and_Guillermo_del_Toro. (researchgate.net)

The Shape of Water. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, March 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Shape_of_Water. (en.wikipedia.org)

Show the Monster. The New Yorker, 7 Feb. 2011.

I always learn something new when I read your posts. I am going to look further into Open Culture. It looks like a good resource for a lot of different things.

Del Toro is amazing and has such a great eye.