Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) stands as a singular figure in modern and contemporary art. Over a career spanning nearly eight decades, she created a body of work that confronts personal trauma, memory, and the complex dynamics of human relationships. While best known for her monumental sculptures and intimate installations, Bourgeois’s practice draws upon the language of Surrealism, with its emphasis on the subconscious, dreamlike imagery, and symbolic form, as well as the gestural, emotionally charged techniques characteristic of Abstract Expressionism.

Born in Paris in 1911, Louise Bourgeois grew up in a household steeped in the world of textiles and restoration. Her father’s tapestry restoration business not only introduced her to the language of pattern and fabric but also instilled an early awareness of memory and loss. Early works such as the intimate prints in He Disappeared into Complete Silence reveal a preoccupation with abandonment and a desire to process unresolved emotions (Bernadac and Obrist 45). During the 1930s, Bourgeois studied art in Paris; a period when Surrealism was rapidly emerging as a dominant movement. Although she later resisted strict categorization as a Surrealist, her early drawings and prints, which often incorporate biomorphic forms and ambiguous figures, betray an interest in unlocking the unconscious (Morris 26). Her practice of reworking images, returning to motifs and materials over multiple states, became a hallmark of her artistic process and prefigured later experiments in both printmaking and sculpture (Wye 12).

Surrealism’s focus on automatic processes, dreams, and the irrational found a strong echo in Bourgeois’s early work. Pieces like her “Spider” series (exemplified by Spider I [1994] and later monumental incarnations such as Maman (1999)) exemplify how she transformed personal memory into symbolic imagery. The spider, for Bourgeois, is paradoxical: it is both a nurturing protector and a menacing figure; a duality that resonates with the Surrealist fascination with hidden desires and repressed anxieties (Nixon 34). Other works such as Home for Runaway Girls (1994) and Fallen Woman (1981) illustrate her use of figurative imagery to evoke states of vulnerability and defiance. In these pieces, the distortion of scale and the uneasy juxtapositions of organic forms recall the dreamlike logic of Surrealist works by Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí, yet they remain intimately autobiographical. Through these images, Bourgeois transforms personal trauma into a visual language that speaks both to the subconscious and to universal human concerns (Tate).

While Bourgeois’s early work shows clear affinities with Surrealism, her later work increasingly reflects the influence of Abstract Expressionism. Working in postwar New York, she absorbed the era’s emphasis on large scale, physicality, and the act of creation itself. Her later “Cells” installations, such as Cell (Eyes and Mirrors) (1989–93) and Cell XIV (Portrait) (2000), employ expansive, enclosed spaces that echo the gestural immediacy of Jackson Pollock’s action paintings and the meditative expansiveness of Mark Rothko’s color fields (Wye 58). In these works, the use of industrial materials (bronze, latex, steel) and the integration of found objects underscore a departure from traditional media. For example, in Maman (1999), Bourgeois constructs a giant spider from bronze and marble that dominates public space while invoking both the protective and predatory aspects of the maternal figure. These works, imbued with raw emotional energy and a physicality reminiscent of Abstract Expressionist techniques, reveal how Bourgeois used material experimentation to translate inner turmoil into form (Morris 112).

Bourgeois’s mature work resists simple categorization by simultaneously drawing on the symbolic, dreamlike aspects of Surrealism and the tactile, gestural energy of Abstract Expressionism. Her later series, such as the “Spirals” (e.g., Spirals (2005) and Nature Study (1986)) and mixed-media installations like I Am Afraid (2009), merge these tendencies. In these works, the spiral becomes a multifaceted symbol: evoking memories of childhood, the rhythmic processes of nature, and the struggle to control chaos. Similarly, her installations known as “Cells” serve as enclosed environments that reflect internal states of isolation, fear, and hope. These immersive spaces compel viewers to confront both the fragility of human existence and the unyielding persistence of memory. By merging the automatic, subconscious imagery of Surrealism with the large-scale, emotionally charged aesthetics of Abstract Expressionism, Bourgeois creates works that are as intellectually challenging as they are viscerally moving (Nixon 89; Tate).

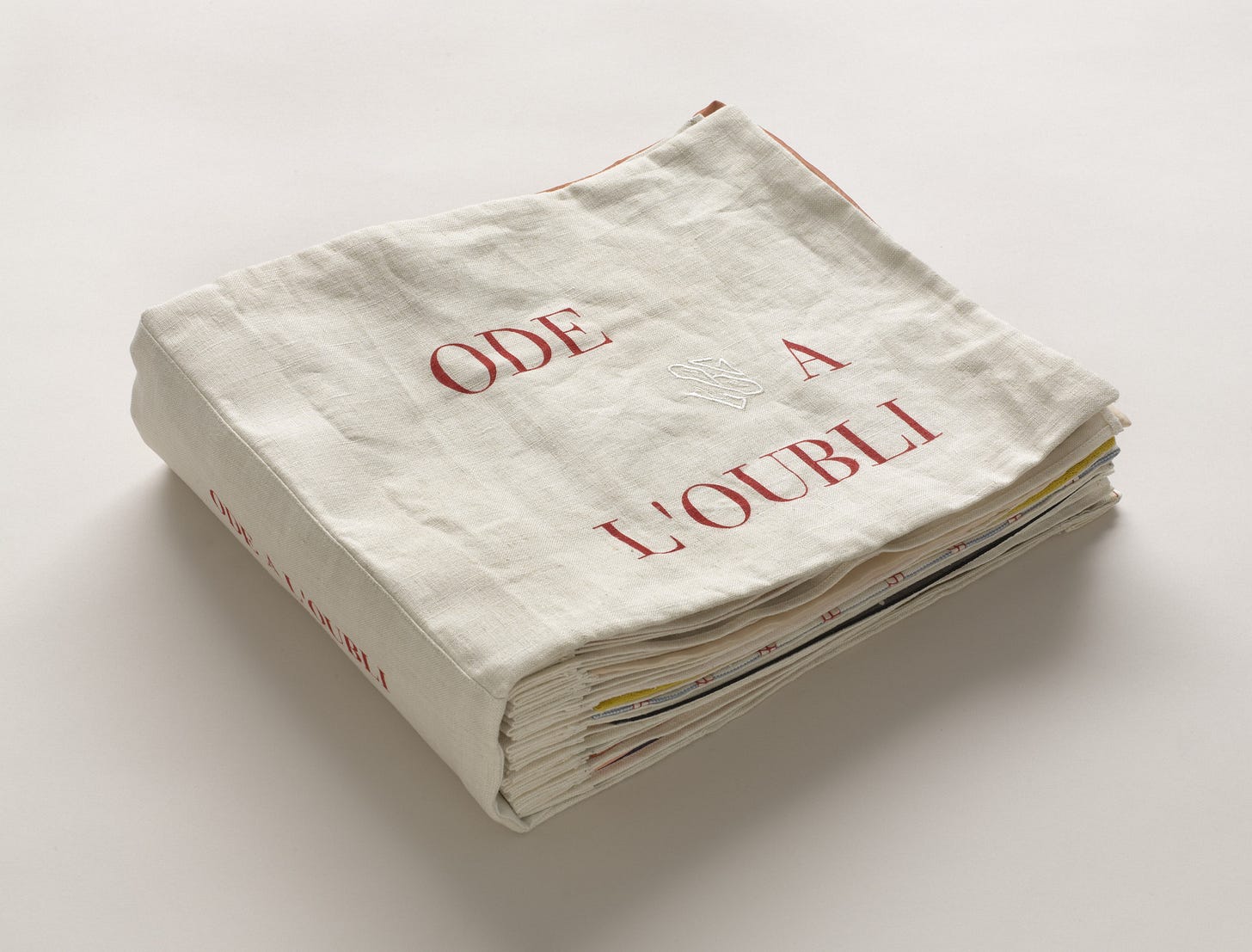

Additional examples reinforce this synthesis. The Destruction of the Father (1974) and Confrontation (1978) incorporate fragmented forms and unsettling materials to evoke complex psychological narratives, while her fabric works, such as I Am Afraid and Ode à l’Oubli (2002, 2004), draw on tactile, domestic materials that recall both her early exposure to tapestry and the physicality of Abstract Expressionism. These works reveal how Bourgeois’s practice evolved into an ongoing dialogue between personal history and broader artistic movements.

Louise Bourgeois’s artistic journey, from her early encounters with the techniques and themes of Surrealism to her later immersion in the physical, emotional intensity of Abstract Expressionism, demonstrates the power of art to transform personal trauma into universal expression. Her work continuously revisits motifs of memory, abandonment, and the body, yet it does so in ways that defy strict stylistic boundaries. By synthesizing the dreamlike logic of Surrealism with the raw immediacy of Abstract Expressionism, Bourgeois forged a visual language that remains vital and provocative. Her legacy endures not only in her monumental sculptures and immersive installations but also in the ongoing dialogue her work inspires among artists, scholars, and viewers worldwide.

References:

Bernadac, Marie-Laure, and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, editors. Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father/Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews, 1923–1997. MIT Press, 1998.

Morris, Frances. Louise Bourgeois. Tate Publishing, 2007.

Nixon, Mignon. Fantastic Reality: Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art. MIT Press, 2005.

Tate. The Art of Louise Bourgeois. Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/louise-bourgeois-2351. Accessed 18 Jan. 2025.

Wye, Deborah, editor. Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait. Museum of Modern Art, 2017.

If ever there was a female artist to counter Francis Bacon’s triggers, for me it is Louise. Almost all of her work puts me in those cages quivering. The overlording of both male and female energies prevent one from finding any safe space. There is no sanctuary in Bourgeois’ work. Only a kind of purging that is unfamiliar and uncomfortable but necessary.

I was triggered by your write up. It’s either you or her. I am counting on the fact it’s still her. A testament to your effective capture of her different stages as they take me back to being a cowering child in the corner.

Whew!

Btw, that’s me liking her work 😂