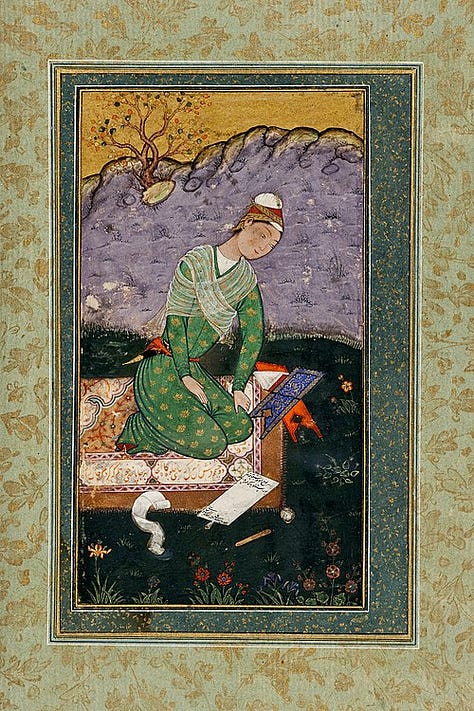

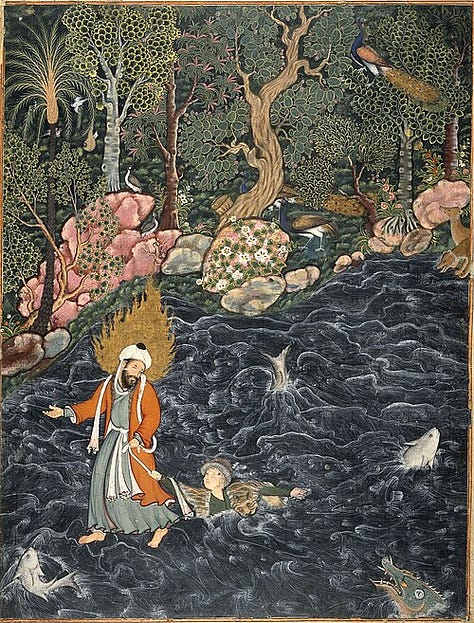

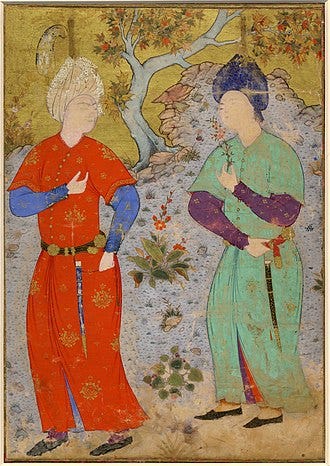

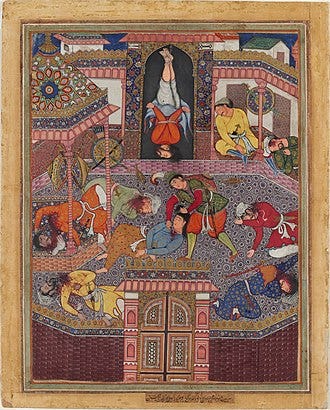

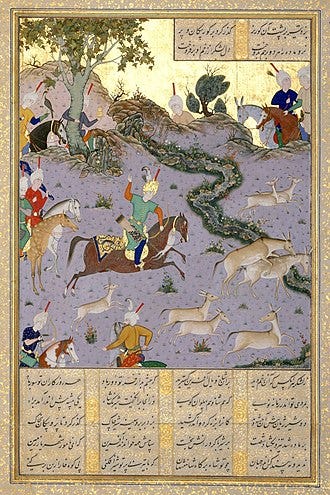

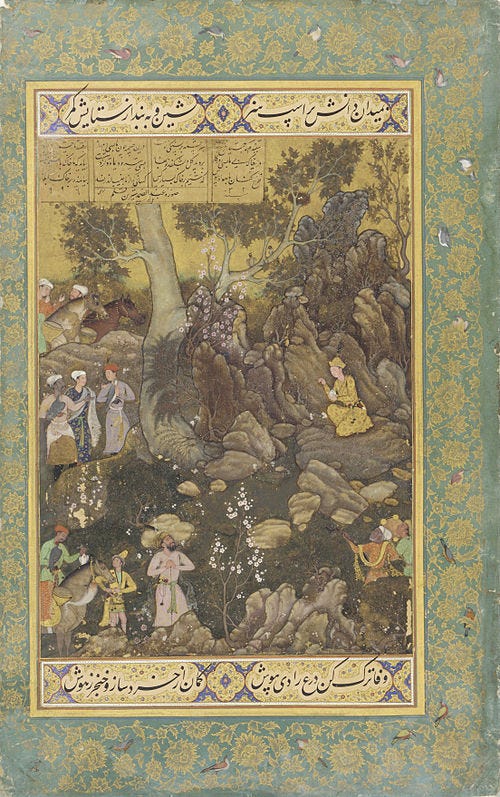

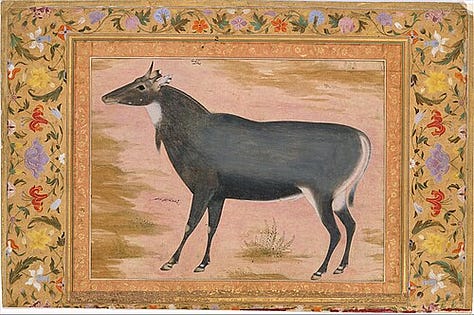

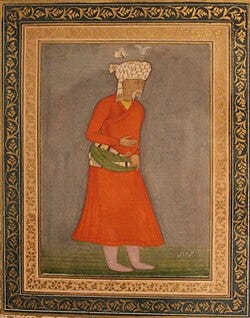

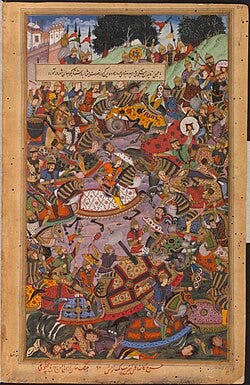

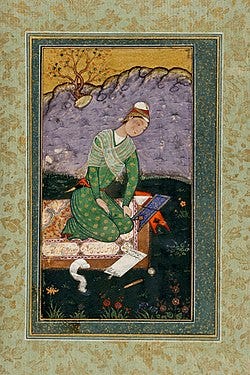

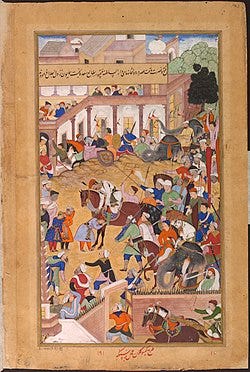

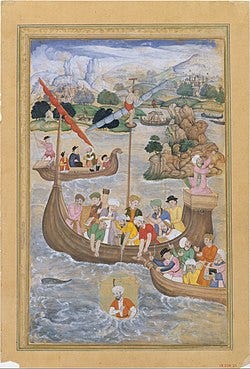

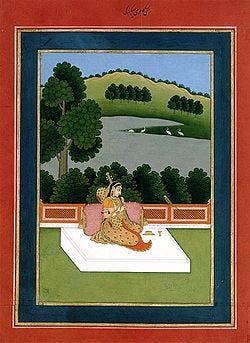

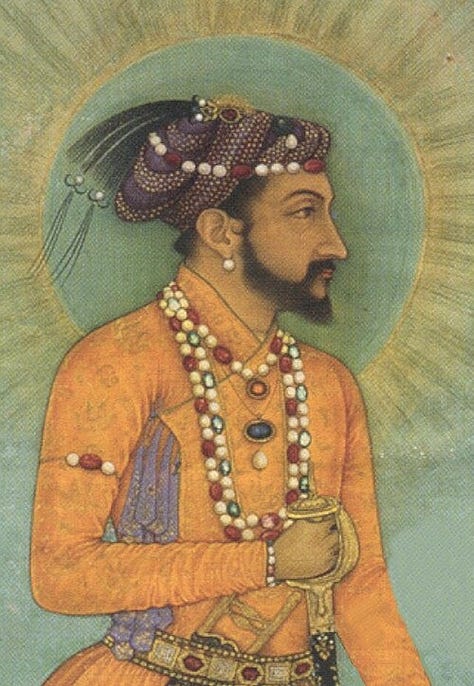

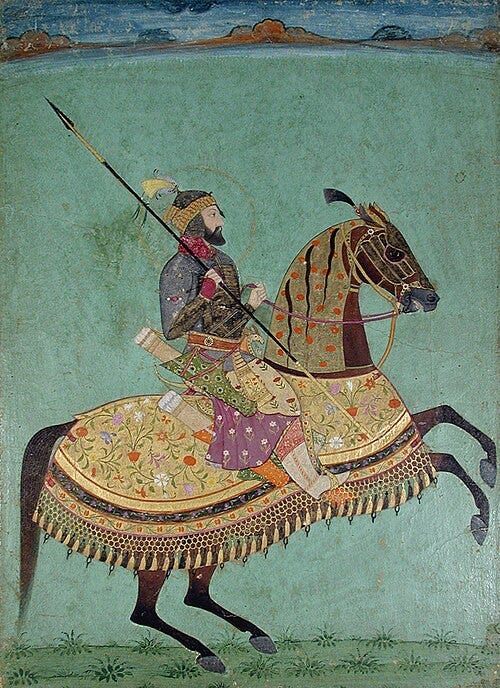

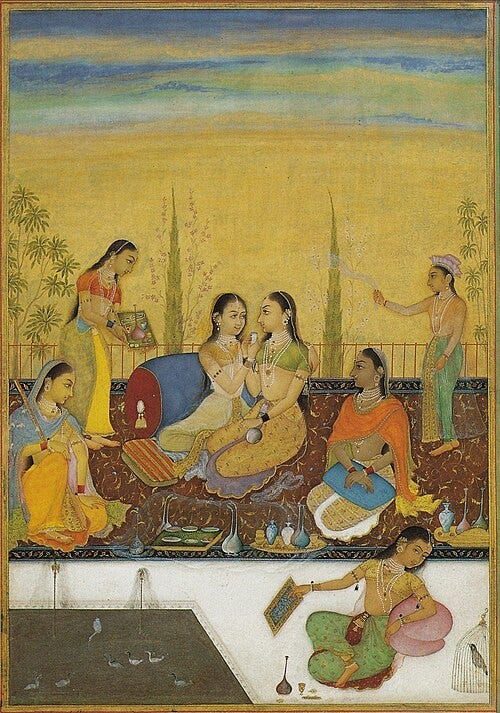

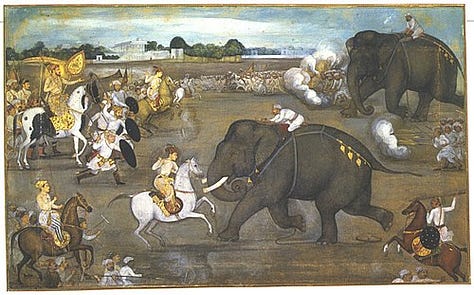

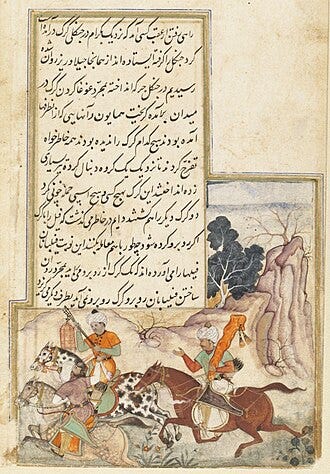

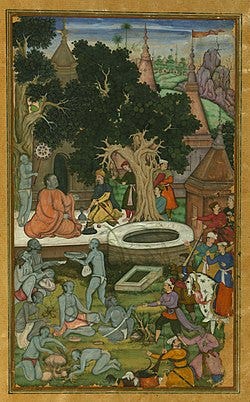

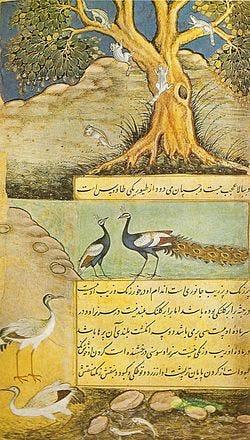

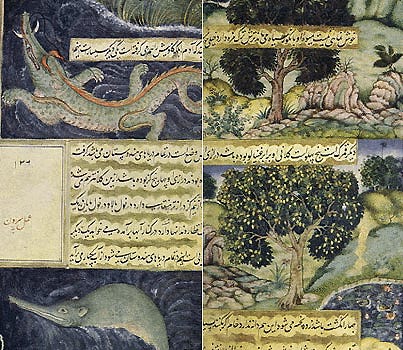

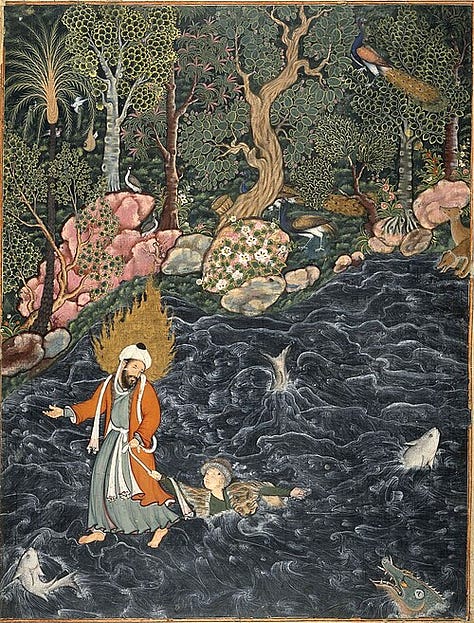

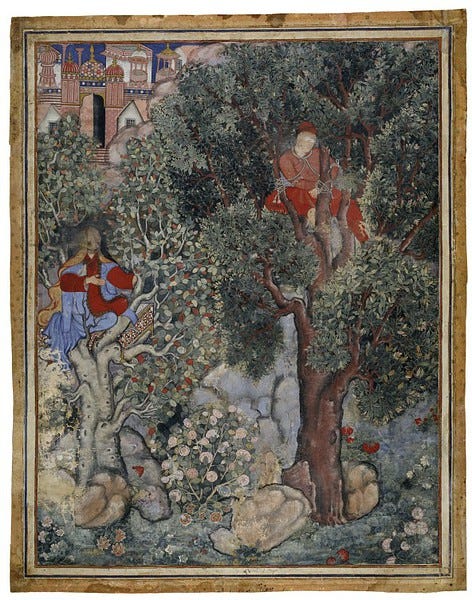

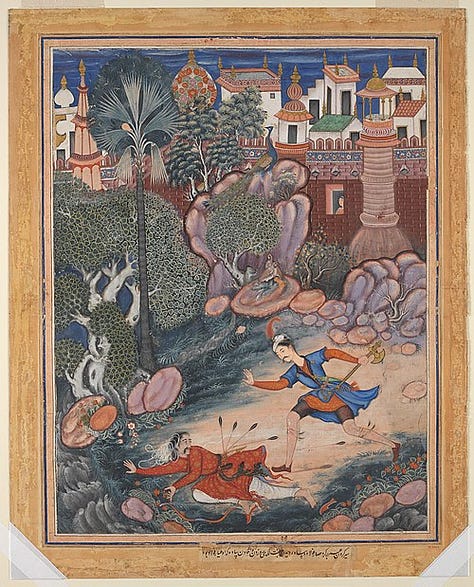

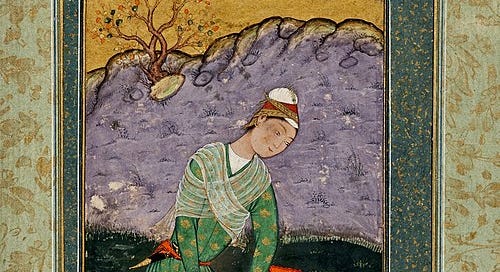

From its inception in the 16th century to its decline under Aurangzeb, Mughal miniature painting was a syncretic art form blending Persian, Indian, and European elements. Its origins trace to Babur’s establishment of the empire, but it was Humayun’s exile in Persia (1540–1555) that brought Persian painting masters Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad to India, laying the foundation of a distinctly Mughal style. By Akbar’s reign (1556–1605) the imperial atelier grew to over one hundred artists, producing lavishly illustrated manuscripts and evolving the style. Mughal miniatures are characterized by minute precision and vivid color; some details were executed with a single-hair brush, yielding jewel-like hues and elaborate patterning with minimal shading. The subject matter often drew on court life and nature (emperors in bucolic gardens, falconry scenes, flowering plants and exotic birds) reflecting the Mughals’ cosmopolitan tastes. European influence crept in under Jahangir (1605–1627) and Shah Jahan (1628–1658), as the emperors invited European artists and incorporated linear perspective and realism into portraiture. Miniatures under Jahangir especially reached “an unprecedented level of naturalism” as seen in sensitive facial likenesses and botanical detail. The later Mughal emperors continued the tradition to varying degrees, but under Aurangzeb (1658–1707) patronage waned. By Aurangzeb’s death the workshop tradition had largely faded, and many miniatures were lost or dispersed to Europe.

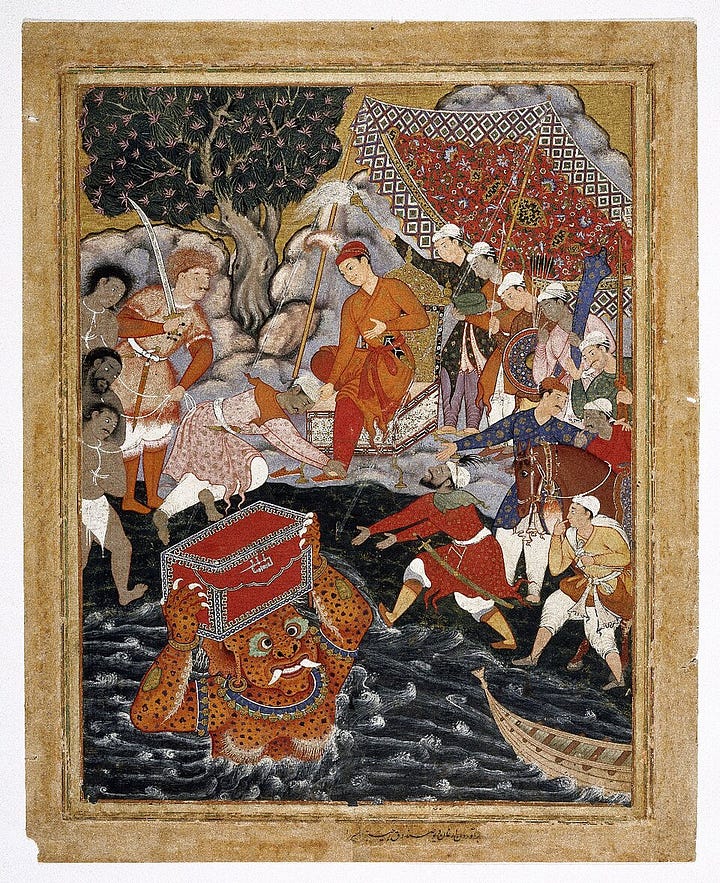

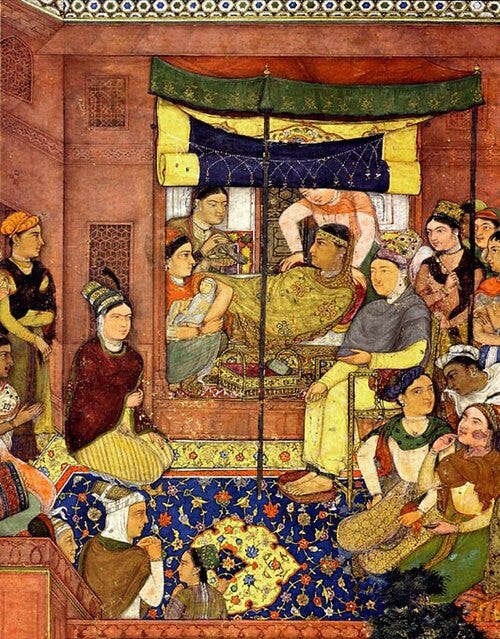

Such paintings exemplify the Mughal penchant for intricate detail and hybrid motifs. Influences from Safavid Persian manuscripts are evident in the refined calligraphy and shading, while Indian elements brought vibrant pigments and dynamic compositions. Just as the empire united diverse peoples, Mughal miniatures “drew from India, Persia, and Europe to create something entirely new”. This fusion is seen, for example, in botanical scrolls influenced by Jesuit prints, and in narrative scenes like the imperial Hamzanama (1562–77) illustrating a mythical epic. Over time the Mughal atelier perfected a collaborative technique: one artist might design and outline figures, another fill in color, and apprentices work on background or ornament. No other court art demanded such exacting skill or such subtle brushwork. In sum, Mughal miniature painting evolved from its Persianate roots into a sui generis style, lavish yet meticulous, mirroring the empire’s ambition to synthesize cultures and depict an idealized reality at the emperor’s court.

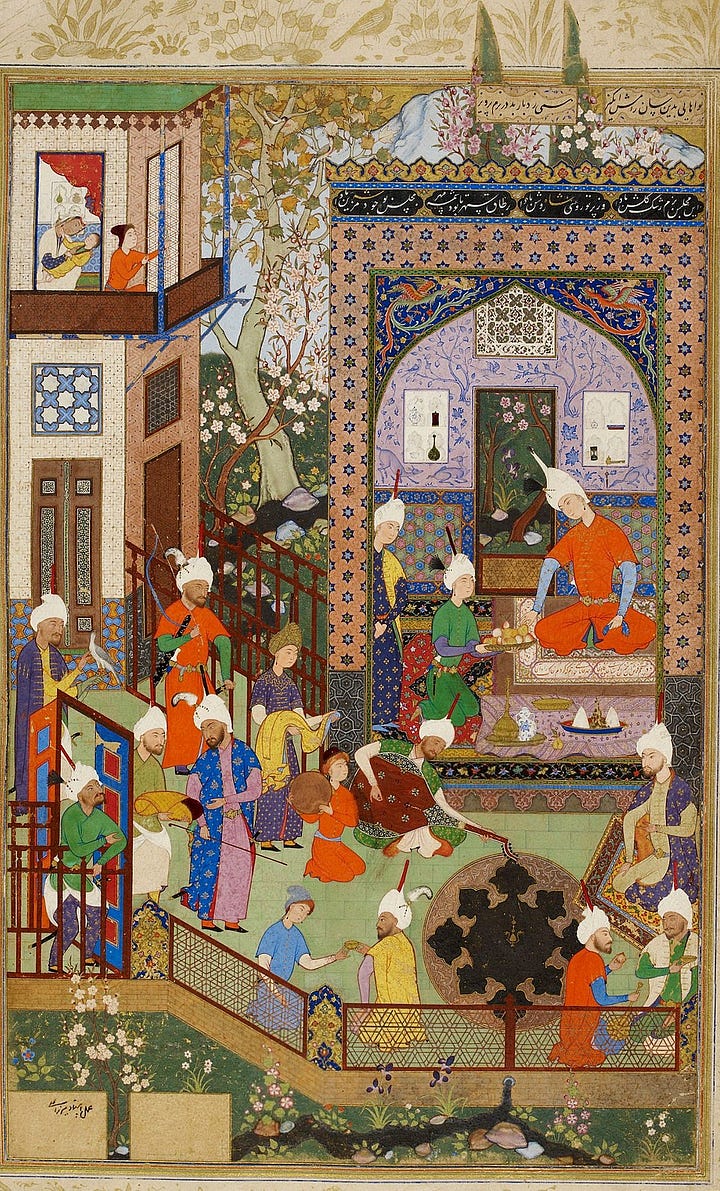

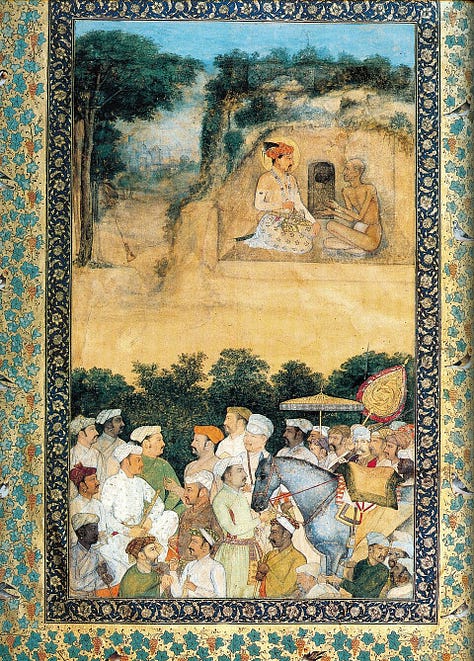

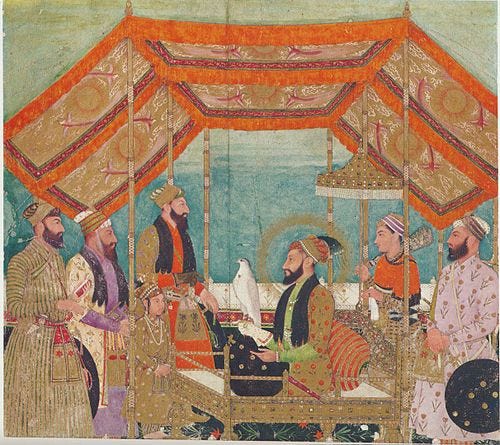

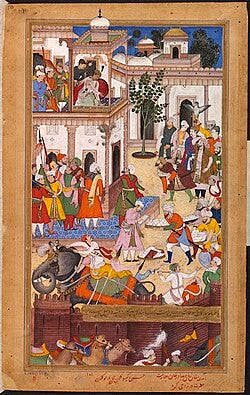

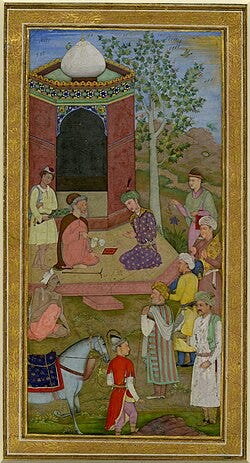

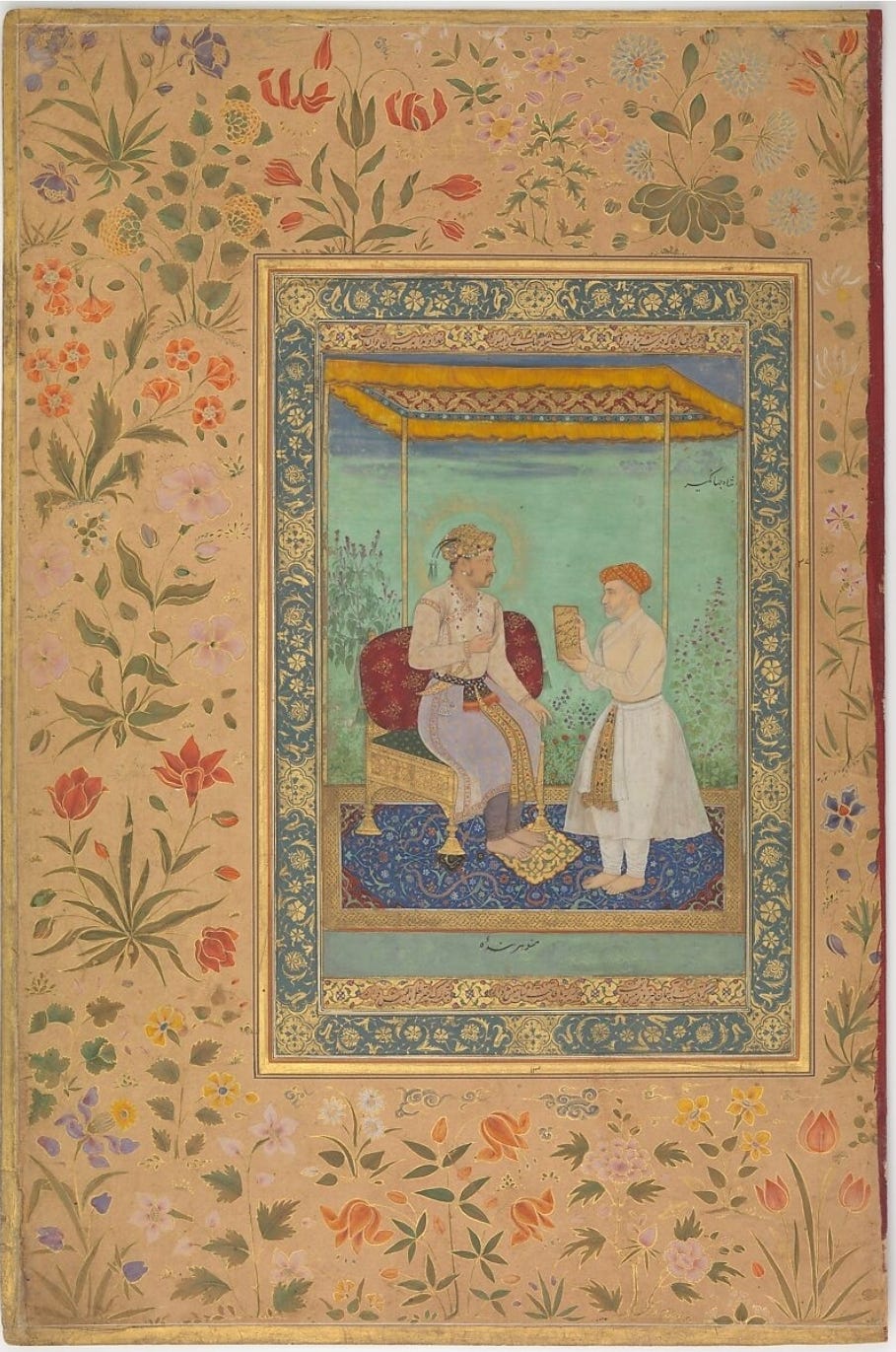

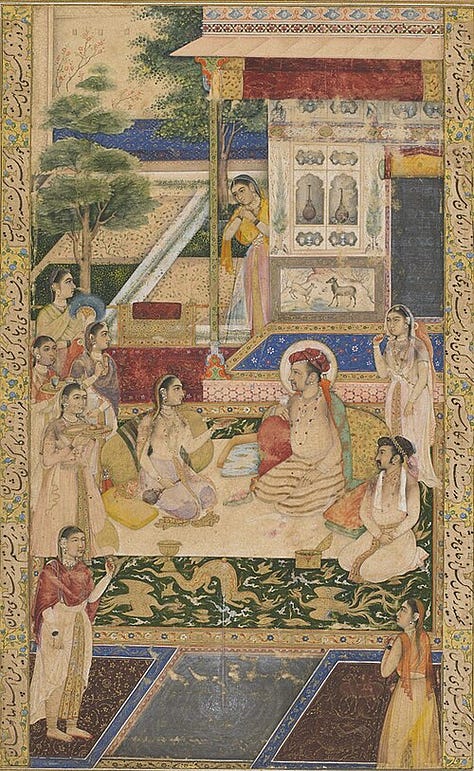

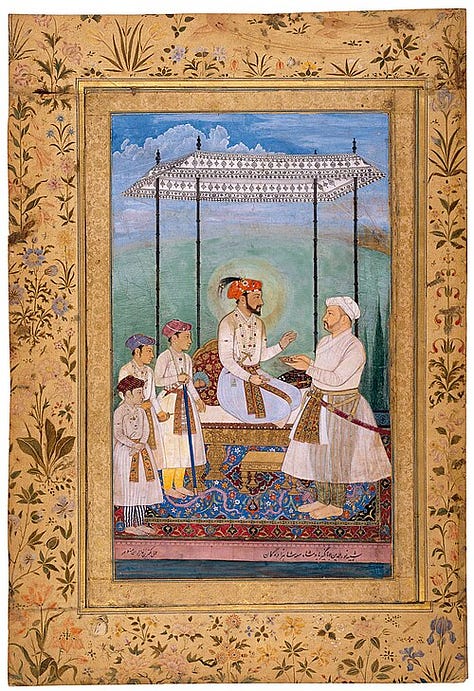

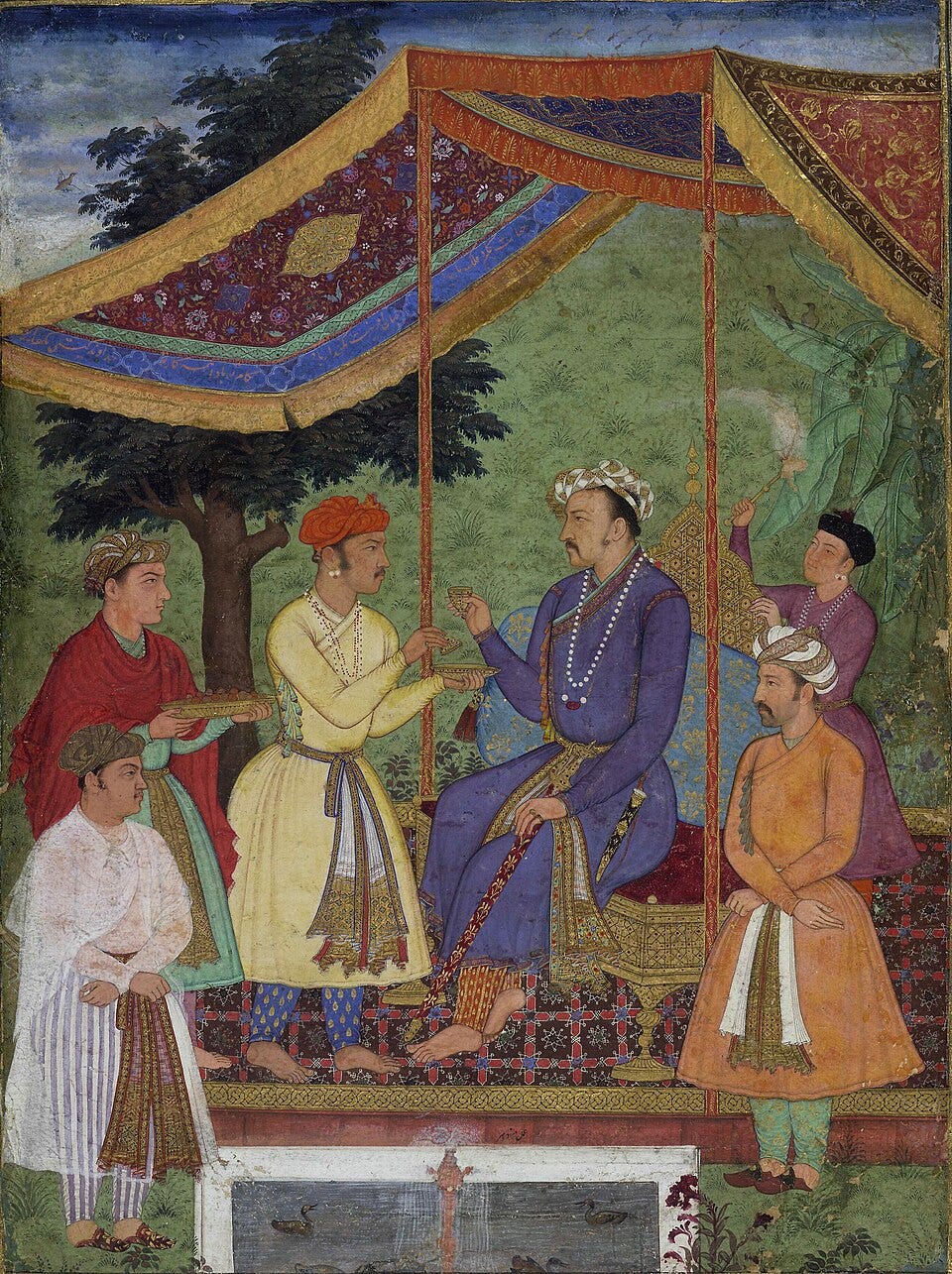

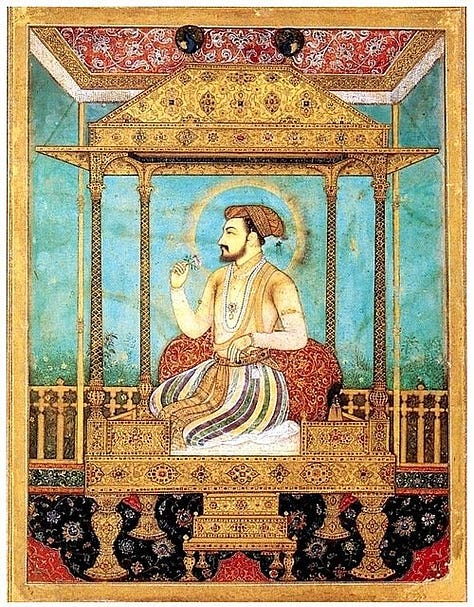

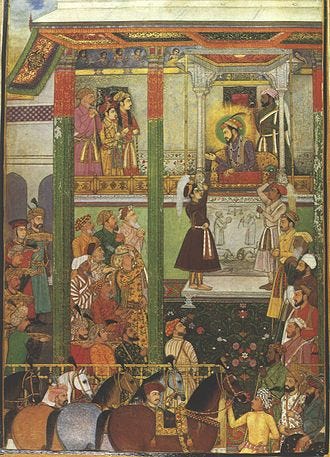

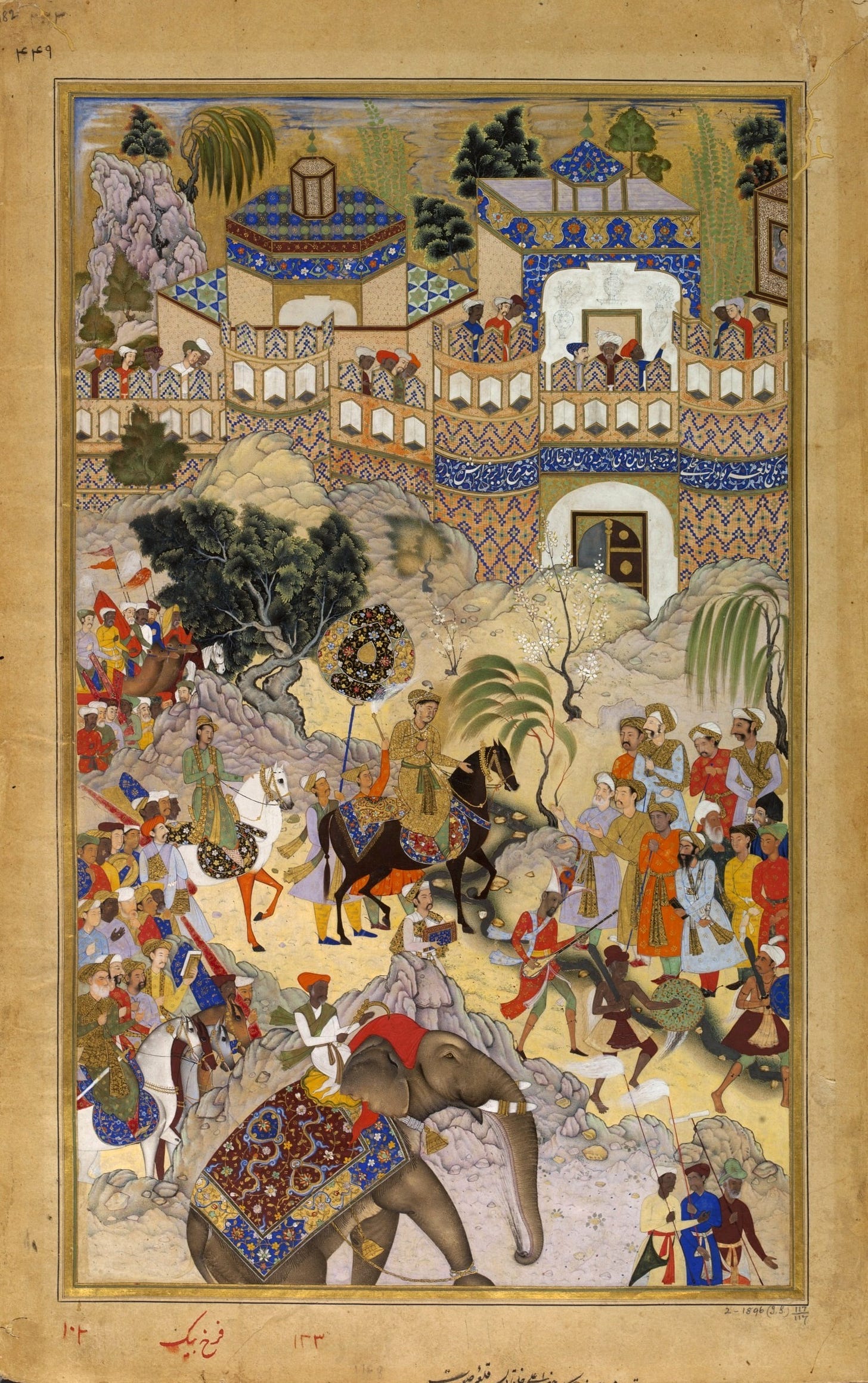

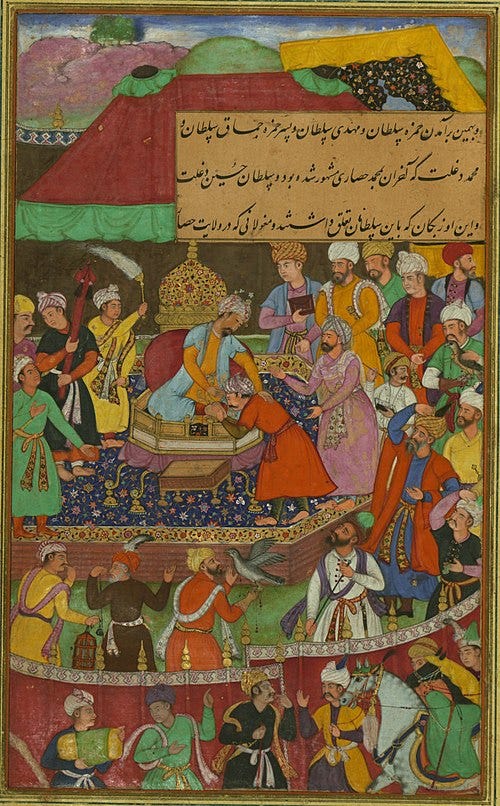

Mughal miniatures placed a new emphasis on portraiture and court scenes that conveyed imperial opulence and authority. A hallmark was the lifelike depiction of emperors, nobles and commoners, often in formal court assemblies, prayer sessions, or pageants. Under Akbar, artists began producing individual likenesses (e.g. Jahangir weighing Prince Khurram), but it was Jahangir who made portraiture a pinnacle of the arts. His painters studied European prints brought by visitors and wives, which taught the use of shading and realistic light. As a result, court portraits under Jahangir exhibit “unprecedented naturalism”, facial expressions, gestures, and textures of textiles and gems are recorded with near-ritual precision. Emperors delighted in these images as symbols of their presence and cosmic order. Group portraits and historical scenes also flourished; individual courtier portraits were copied into larger assembly paintings (for example, a portrait of Nawab Ghazi Mardan Khan became a figure in a garden audience scene with Jahangir).

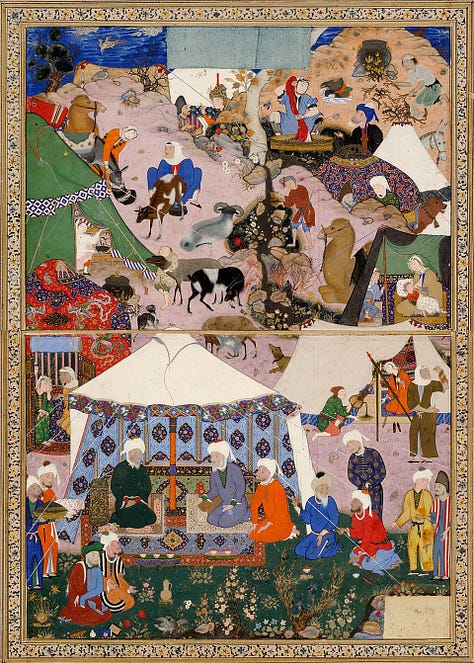

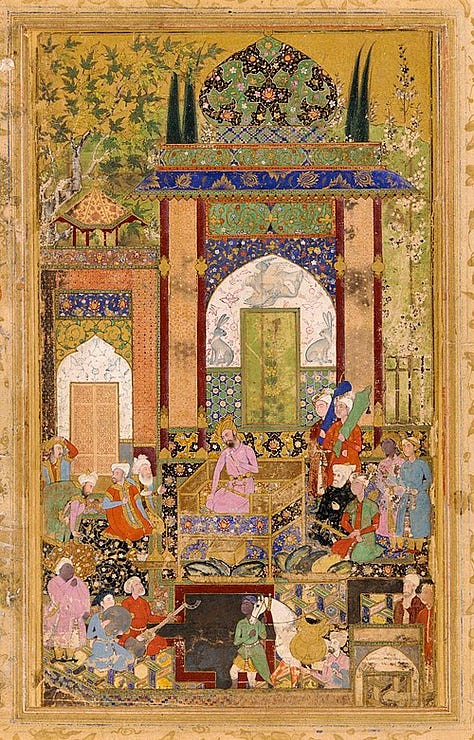

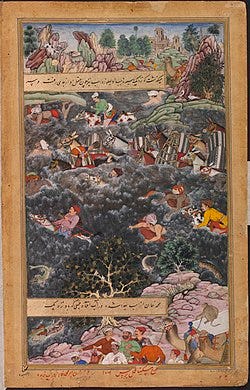

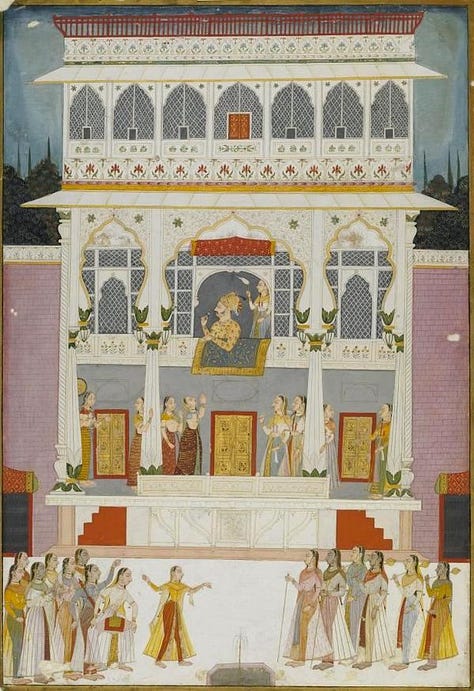

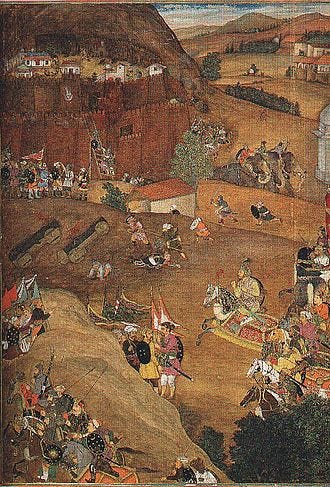

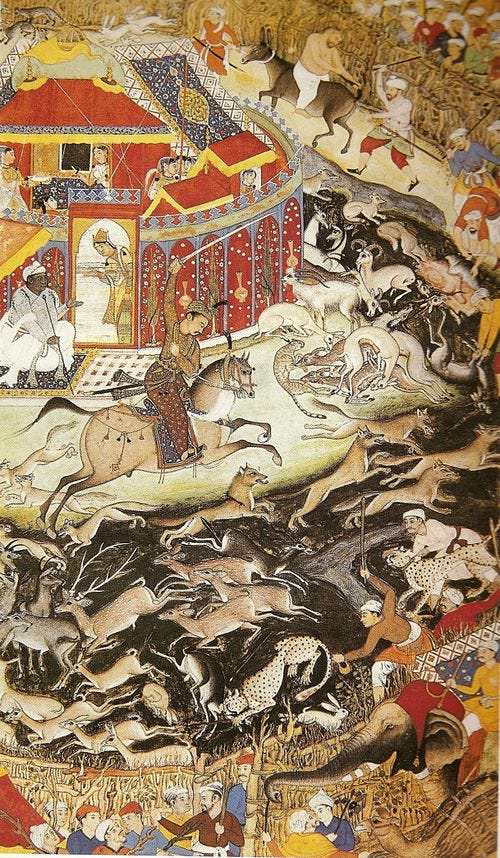

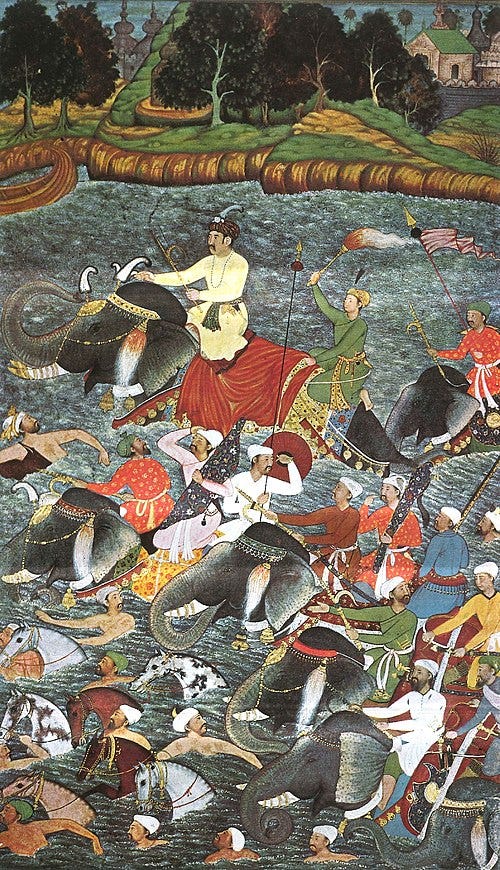

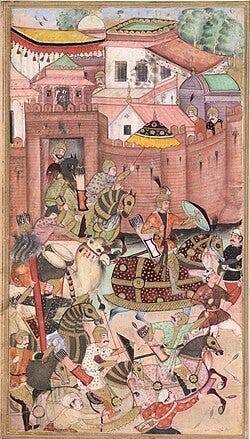

Court life (banquets, music, dance, hunting, and administrative rituals) provided rich subject matter. Miniatures famously depict lavish parades, elephant processions, and auspicious festivals, often set against palatial architecture or lush gardens. For instance, scenes of royal hunts show the emperor on horseback with falconers or tigers, underscoring his mastery over nature. Pomposity and pageantry abound; the Jharokha Darshan (daily audience) paintings of Akbar, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb capture them on decorated balconies surveying subjects, emphasizing their divine right to rule. Even leisure is luxurious; album pages show ladies in zenana gardens, flanked by attendants and musicians. These images were propaganda as much as documentary. They broadcast the emperor’s wealth (golden thrones, jeweled finery) and the court’s cosmopolitan cosmology. Indeed, scholars note the Mughal empire at its zenith controlled about 25% of the world’s GDP, and the art reflects this abundance; textiles glisten in gold and gems, and architecture looms inlaid with marble.

Jahangir enthroned and receiving his son, from a Mughal court painting (c. 1610) exemplifies how portraiture and assembly scenes conveyed imperial authority. Portraits and court scenes thus served both as commemorative records and theatrical statements of power. By the 17th century, Mughal patrons like Shah Jahan even commissioned portrait albums, while chronicles (like the Padshahnama) were lavishly illustrated with visual narratives of the emperor’s life. Through these images, we see the rituals and splendors of Mughal rule rendered with exactitude, as much to impress their subjects and foreign dignitaries as to document the golden age of Mughal courts.

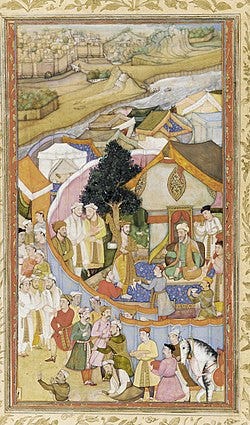

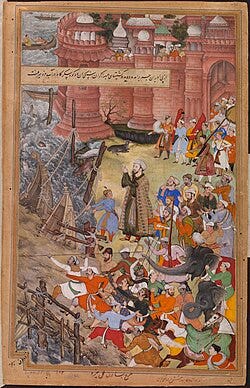

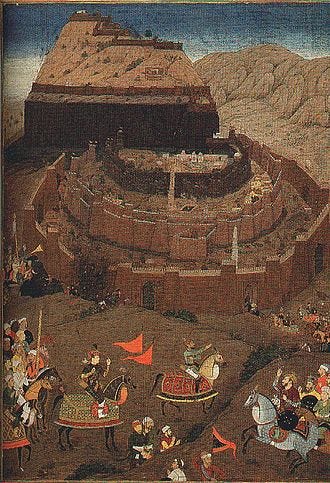

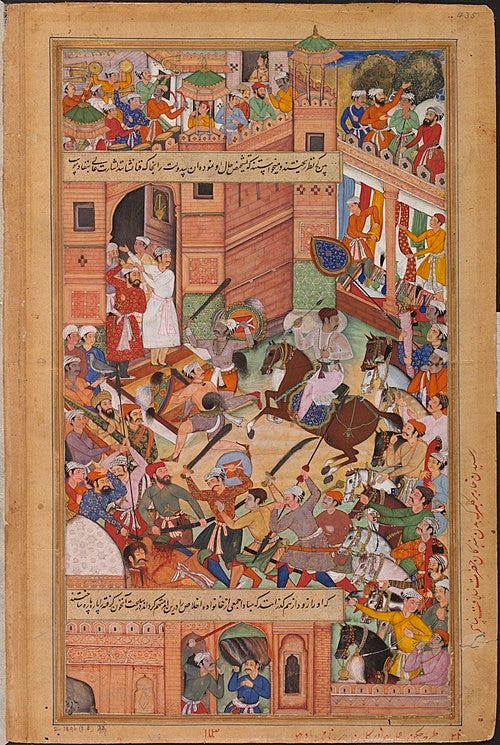

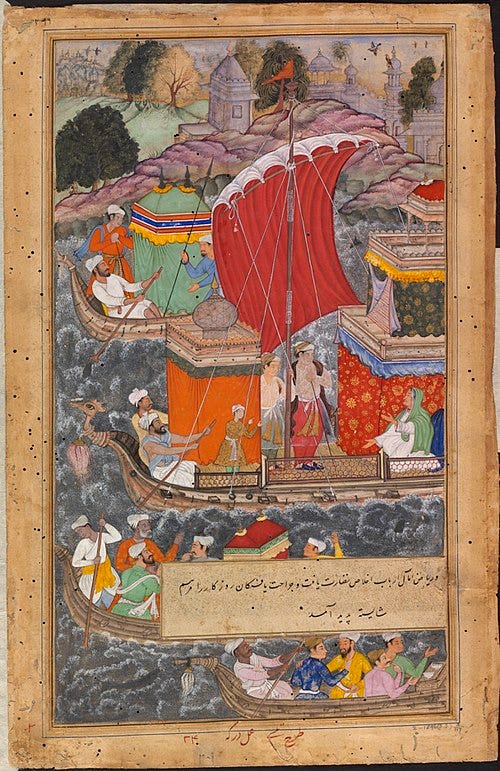

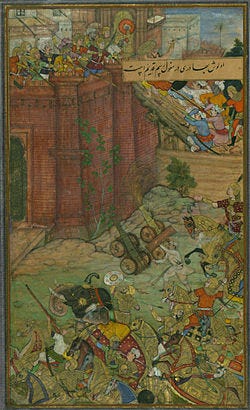

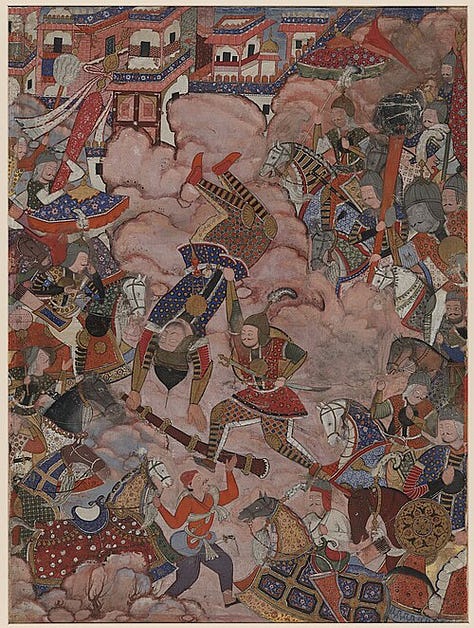

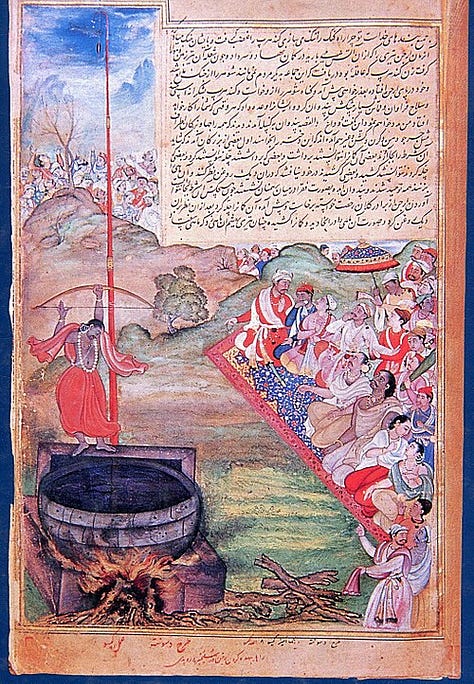

Imperial chronicles and epics provided the grandest canvases for Mughal painting. Chief among these was the Akbarnama, the official history of Emperor Akbar compiled by courtier Abū al-Fazl (completed 1596). It was conceived as a visual and textual statement of kingship. The project involved dozens of artists working in Akbar’s atelier; one deluxe copy alone contains around 116 paintings. These miniatures are historically charged scenes (battles, imperial processions, and key events of Akbar’s reign) interspersed with allegorical and courtly episodes. The Akbarnama images follow Safavid courtly style (Emperor enthroned under royal canopy, with Persianate flora and legend), but also experiment with new perspectives. For example, the entry of Akbar into Surat (1589) uses vanishing-point perspective to convey depth, a technique likely learned from European prints. This marked a turning point; Mughal painters began incorporating a modest sense of space into their compositions. The collaborative nature of production is evident in how each page is laid out: an artist (designers) would create a detailed drawing, others would apply color and burnished gold, and the chief master added finishing details. The result is a dense, jewel-like image with many figures, all carefully stylized and annotated in Persian script with verse and commentary.

Other manuscripts followed similar grand designs. Babur’s memoirs, the Baburnama, originally written in Turkic and translated into Persian by Akbar’s court, were illustrated in later reigns. A known fragment from the Walters Art Museum shows about 30 miniatures of Babur’s life, scenes of gardens, battles, and courtly ceremonies, executed in the Mughal style of the 16th century. Akbar also commissioned the Hamzanama (c.1562–1577), an enormous 12–14-volume epic of the warrior Hamza; its 1,400 pages (with about 1,000 paintings surviving) represent the genesis of Mughal painting. The Hamzanama images are larger than typical pages and feature dynamic action, vivid colors and swirling compositions reflecting both Persian lore and local folklore. Later Mughal emperors continued the manuscript tradition: Jahangir oversaw illustrated versions of Hindu epics (the Razmnama, a Persian Ramayana) and Shah Jahan sponsored the Padshahnama (the chronicle of his own reign). Each of these works was more than history; it was propaganda and cosmology on paper.

Technically, these illustrated manuscripts employed opaque watercolor and gold on hand-made paper, with miniature scales often only 7–15 cm high. Painters paid exacting attention to costume, weapons, and architecture as symbols of authenticity. Calligraphy and border designs,.often derived from Persian luxury-book styles, frame each image. Inscriptions sometimes identify the scene or quote poetry. The Mughal emphasis on art produced texts that are unmatched in visual richness. As one museum curator notes, “for all their devotional content, these illustrated manuscripts also reveal just how worldly and materialistic Akbar’s vision of kingship was”. Whether chronicling conquest or courtly life, Mughal manuscripts fused narrative history with the empire’s exquisite aesthetic.

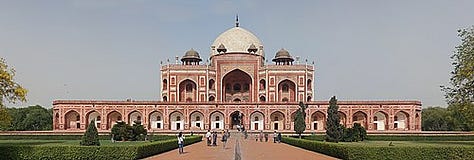

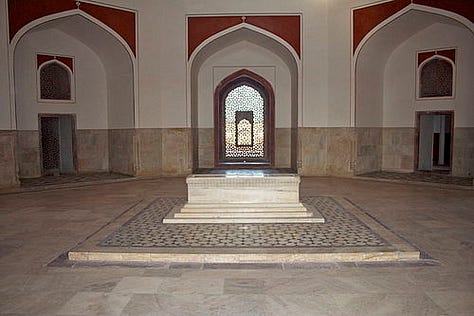

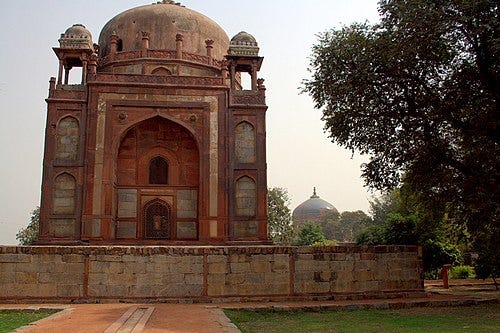

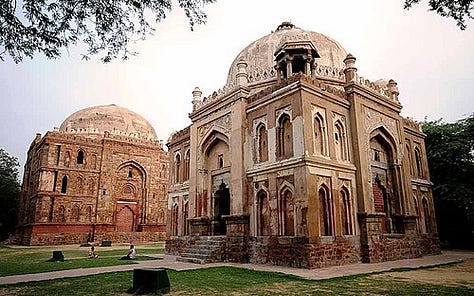

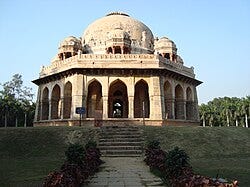

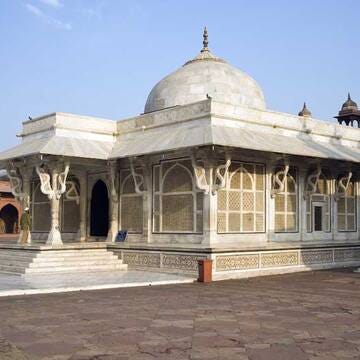

Mughal emperors commemorated their dead with monumental tombs, merging architectural innovation with symbolic meaning. The prototype was Humayun’s Tomb (Delhi, completed 1572 under Akbar). It was the first Persian-style charbagh garden tomb in South Asia, explicitly fashioned as an earthly paradise. Perched on a high plinth amid a formal four-part garden, the mausoleum’s massive red sandstone and marble façade signaled Mughal power on an unprecedented scale. UNESCO notes that Persian and Indian craftsmen “combined to build far grander tombs than any before in the Islamic world”. Humayun’s Tomb thus established the formula: a square tomb chamber topped by a grand dome, surrounded by minarets and extensive reflecting pools in a Persian garden. This design symbolized both the garden of paradise (chaharbagh) and the emperor’s divine status as a ruler. Indeed, Humayun’s tomb directly inspired later mausolea, culminating in the Taj Mahal.

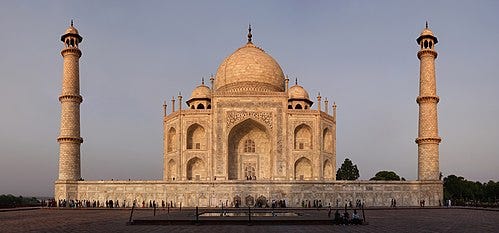

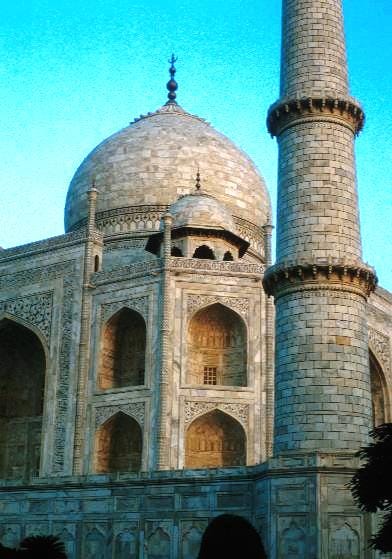

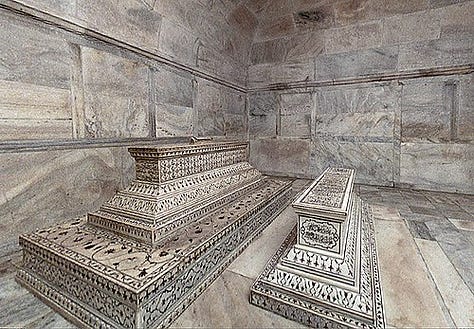

The Taj Mahal epitomizes Mughal funerary grandeur. Built by Shah Jahan in memory of Mumtaz Mahal (completed 1653), the white-marble cenotaph combines Persian, Islamic, and local Indian design elements in harmonious balance. Architects intentionally stressed symmetry; every element along the central axis, from the avenue of trees to the flanking guesthouses, mirrors its counterpart. Shah Jahan’s era saw the “architectural maturity” of the style; Symmetry along a central axis, columnar forms and curving domes, and vegetal arabesque motifs became defining features. The Taj’s dome, a bulbous Persian-style double dome, along with its four slender minarets, achieve a perfect equilibrium. Symbolically, the Taj is conceived as an “earthly replica” of Mumtaz’s heavenly abode, evoking Islamic notions of paradise (jannat). The use of white marble and inlaid pietra dura (see below) further conveys luminosity and refinement. As a late commentary observes, the Mughal builders “conceived the Taj Mahal as a powerful emblem of Mughal authority and divine favor”.

By contrast, Shah Jahan’s own tomb (the yet-uncompleted Mubarak-Maqbara in Delhi) and the tombs of other Mughal nobles are smaller, but Humayun’s Tomb and the Taj remain the grandest. Both exemplify the Mughal synthesis of Persian form with Indian craft. The Taj architects proudly acknowledged Persian roots (the Mughals saw their empire as native to India, but culturally inherited from Persia). The effect is unmistakable: the Taj’s polished marble surfaces and serene gardens reflect a celestial ideal, and its precise proportions and inscriptions present a theology of royal perfection.

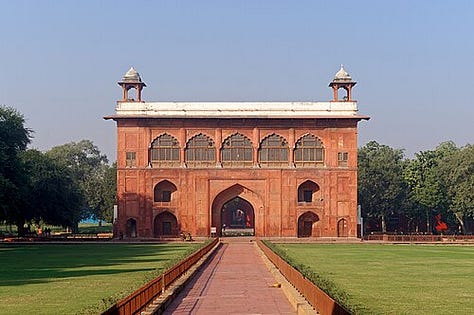

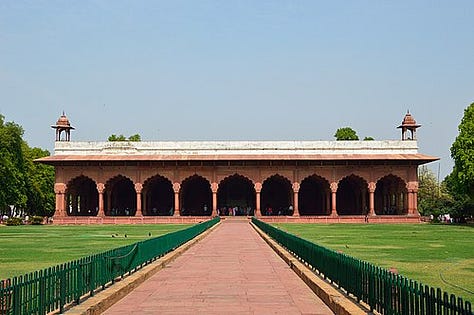

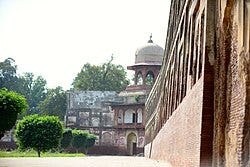

Mughal emperors also expressed authority through massive forts and palaces that combined defensive strength with imperial prestige. Two celebrated examples are the Red Fort in Delhi and the Fatehpur Sikri complex.

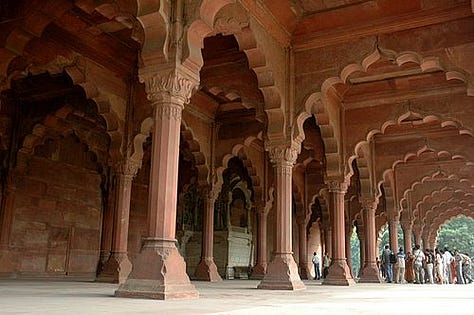

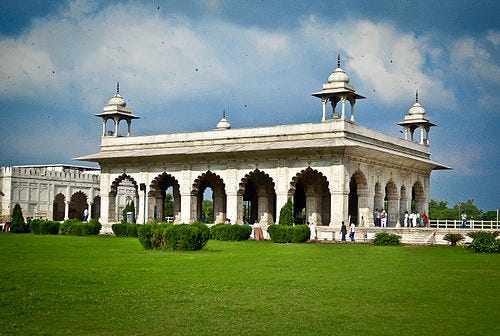

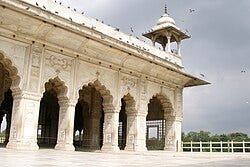

Shah Jahan shifted the capital from Agra to Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi) in the 1630s and built the Red Fort (Lal Qila) as his palace-fortress. This sprawling complex of walls, gates, and halls, constructed of red sandstone, became the ceremonial seat of Mughal power. It mirrors Persian fortress tradition but adapts many indigenous features (e.g. the Persian-style bulbous domes set atop multi-arched halls, and charbagh courtyards). The architectural ensemble (Diwan-i-Aam, Diwan-i-Khas, Moti Masjid, etc.) is richly decorated with pietra dura, filigreed screens and gardens. The Red Fort’s layout (axes along the Yamuna river) and its towering Dara Shikoh’s, reflect a blend of utility and ceremonial splendor. Despite its name, the Anguri Bagh (grape garden) and palatial halls reveal Mughal luxury rather than just fortification.

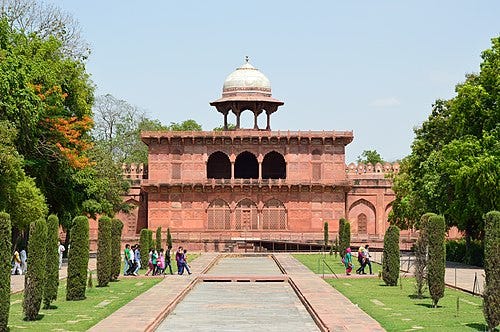

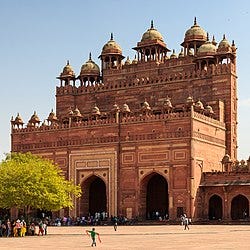

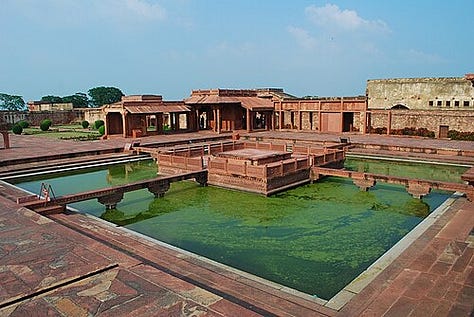

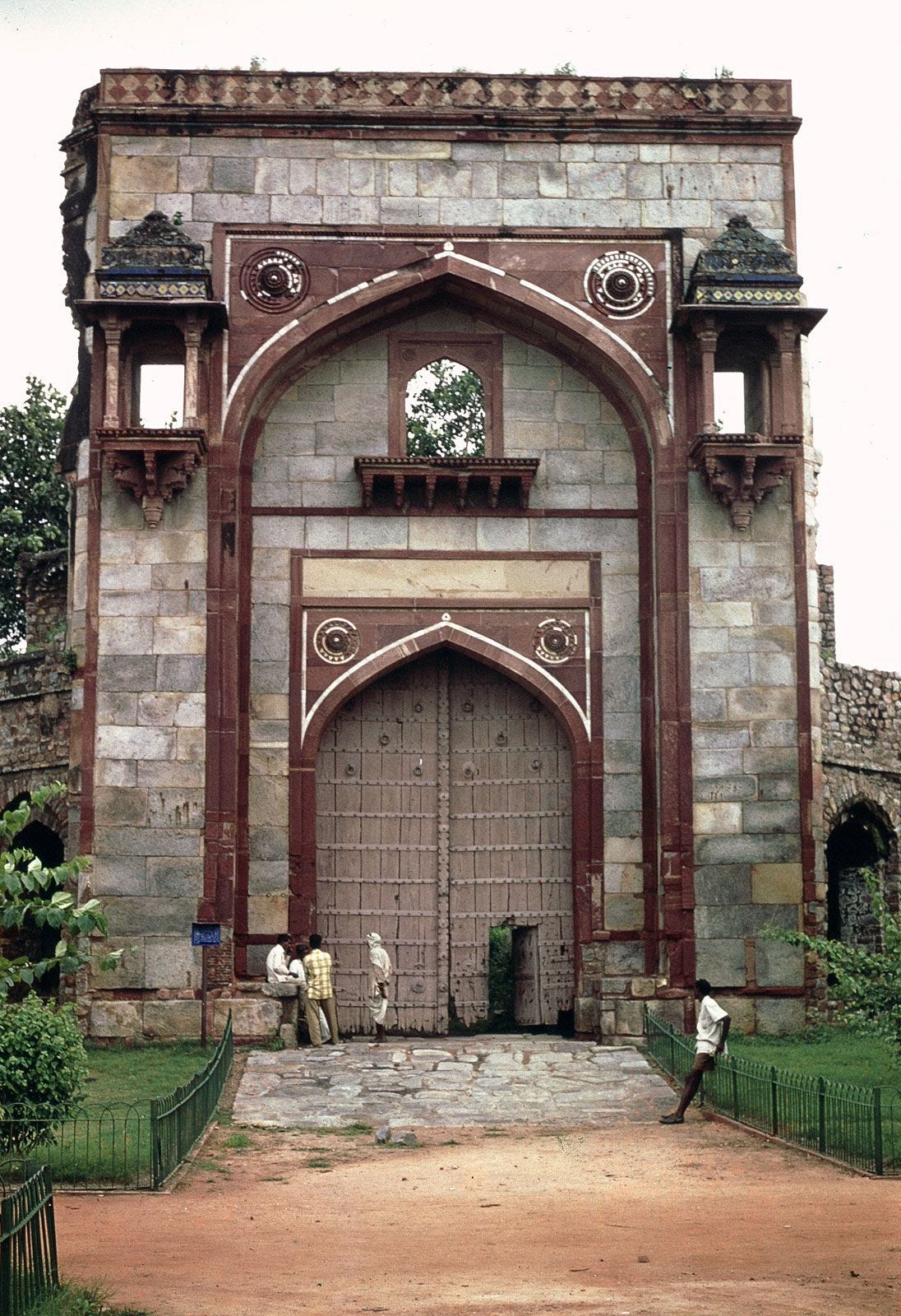

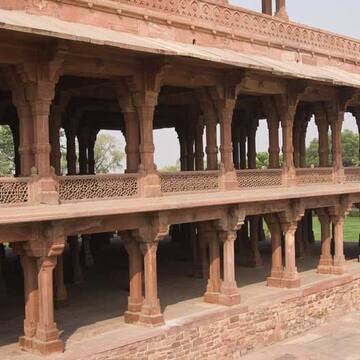

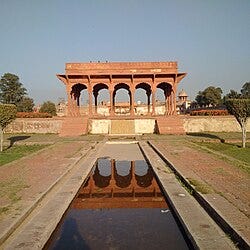

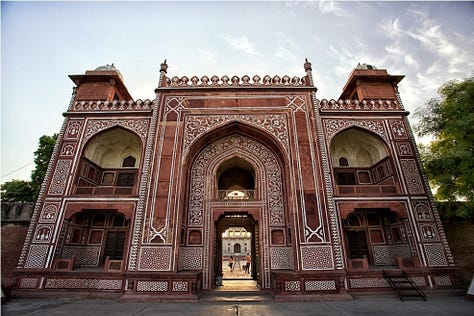

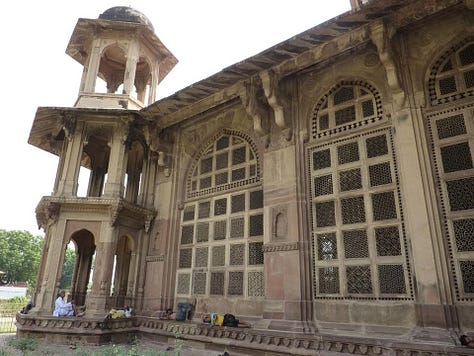

Earlier, Akbar had relocated the capital to Fatehpur Sikri in 1571 and built an even larger palace-city. Fatehpur Sikri’s monuments, all in red sandstone, display a confluence of styles: largely Hindu/Gupta plan forms (e.g. pavilions on columns) fused with Persian decorative motifs. For example, the imposing Buland Darwaza gate and the Jama Masjid arcade recall Persian models, but the delicate floral carving and the chief architect’s (Gulbarn’s) finials are pre-Islamic in inspiration. An inscription praises Fatehpur Sikri as a “most splendid (and valiant) city” of Shahenshah Akbar, reflecting its dual role as spiritual site (honoring Sheikh Salim Chishti) and imperial showpiece. UNESCO notes that Fatehpur Sikri’s architecture “reflects the cultural diversity” of the empire, blending Turkic and Hindu craftsmanship. Indeed, Akbar’s own palace (built around Diwan-i-Khas) and the private quarters showcase jharokha balconies and exquisitely carved stone screens (much like later jalis) that announce Mughal aesthetics. Though Fatehpur Sikri was abandoned (mostly due to water shortages) in the early 17th century, its buildings set a stylistic template that Shah Jahan later refined in the Red Fort and elsewhere.

These fort-palaces were mighty statements of imperial dominance; visible to foreign envoys and pilgrims alike. As one historian notes, the Mughals often modelled their grand gateways and mosques on earlier monuments (e.g. the Red Fort’s Diwan-i-Khas dome is “modeled on Fatehpur Sikri”), yet they always amplified the scale and ornament to new heights. The result was monumental urban complexes (the Red Fort housed tens of thousands at its peak) that functioned as both administrative capitals and sumptuous homes – living embodiments of Mughal absolutism.

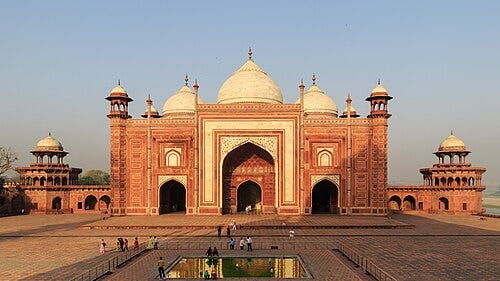

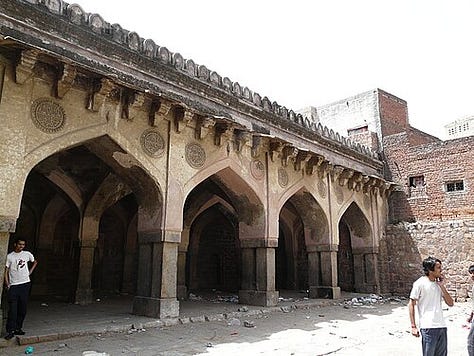

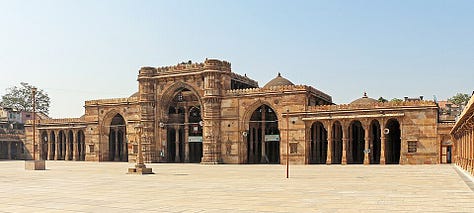

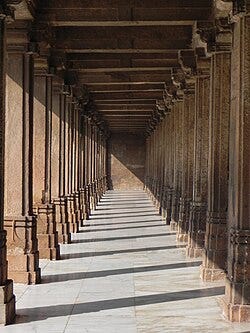

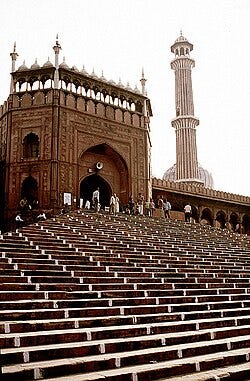

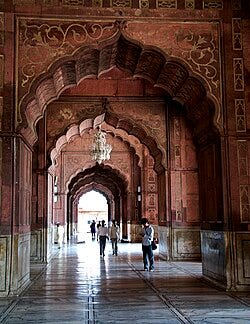

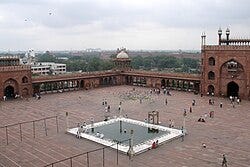

Mosques of the Mughal era likewise combined grand scale with refined elegance. The crown jewel is Delhi’s Jama Masjid, completed 1656 by Shah Jahan. Set on an elevated plinth, it was the largest mosque in the Indian subcontinent at its inauguration, designed to hold 25,000 worshippers. Its architecture epitomizes Mughal mosque design: three bulbous marble domes flanked by lofty minarets, a vast rectangular courtyard, and an arcade of red-sandstone arches. Archnet describes it as the apotheosis of Indian mosque style, drawing both on earlier Delhi models and on Akbar’s Fatehpur Sikri Jami Masjid. The mosque’s facade and court are richly inlaid, with Quranic calligraphy and geometric tilework, creating a visual tapestry of white and vermilion. Its central iwan (arched doorway) with towering pishtaq is directly inspired by Persian prototypes (such as the mosques of Shiraz), reflecting the Mughals’ self-image as heirs to Islamic empires.

Another notable example is the Jama Masjid of Fatehpur Sikri (1569–1571), Akbar’s congregational mosque, which could accommodate 10,000 worshippers. It was built of red sandstone with white marble highlights, and features five entrances to echo Mecca’s five pilgrimage gates. The Fatehpur Jama’s archway design clearly influenced Shah Jahan’s Delhi version; both share a high central iwan flanked by domed pavilions. Overall, Mughal mosques share common features: large courtyards, axial symmetry, four-iwan plans or three-arch facades, and an emphasis on clean geometric forms. They served not only as places of worship but also as public statements of piety and imperial patronage. (Indeed, even Aurangzeb, often criticized for austerity, endowed major mosques such as Lahore’s Badshahi Mosque to cement his legitimacy.) In all these monuments, the scale is impressive, reflecting divine grandeur, while the decorations (calligraphy, arabesques, pietra dura panels, and encaustic tile) exemplify Mughal refinement. In sum, Mughal mosques harmonize utilitarian function with architectural splendor, embodying an empire’s cultural synthesis and religious devotion.

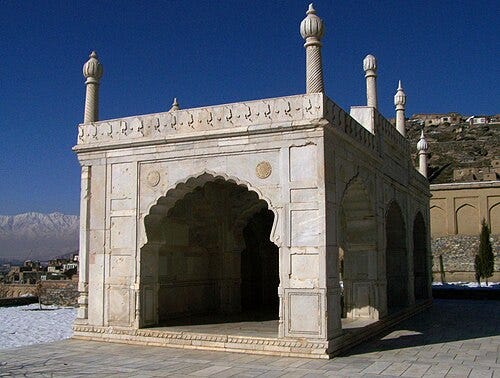

Mughal gardens were conceived as earthly paradises and architectural devices. The Mughals adopted the Persian charbagh layout, a quadripartite garden symbolic of the four rivers of paradise, in many imperial projects. The prototype was set by Babur himself; his garden at Kabul (Bāġh-e Bābar) followed Persian conventions with terraces and channels. Babur insisted on the charbagh’s four-fold symmetry and belief that “one benefit of planting trees is that tomorrow perhaps someone will write a sonnet about them”. Under Akbar and his descendants, nearly every major mausoleum and palace featured such gardens. Humayun’s Tomb sits at the intersection of four watercourses with fountains and pools, representing cosmic order. Shah Jahan applied this scheme to the Taj Mahal; a long reflecting pool runs from the main tomb to a high brick terrace at the entrance, intersected by transverse waterways, with flowerbeds and cypresses laid out in a grid. The overall effect is one of serene geometry: the tomb’s image is mirrored in the water, suggesting the transient and heavenly nature of its occupant’s soul.

The layout and features of Mughal gardens are rich in symbolic meaning. Gardens were enclosed (“paradise walled”) and oriented so that visitors’ paths led toward the central pavilion (sometimes a tomb or pavilion). Water, a precious resource, was organized into channels and terraces to create cooling microclimates. As one study notes, fountains and summerhouses provided both shade and visual delight, with water playing through octagonal tanks and sunken canals. Gardens were also sites of leisure for the court: terraced flower beds, fruit orchards, and whispering pavilions (pavillions open on all sides) allowed the emperor and nobility to stroll, picnic, and entertain. Their Persian heritage is evident in the use of ornamental flora (roses, jasmines, poplars) and inscriptions equating gardening with creating heaven on earth.

Beyond tombs, Mughal love of gardens is seen in places like Shalimar Bagh (Lahore), laid out by Jahangir in 1619 for Nur Jahan. This terraced garden (with three levels of fountains and 410 fountains in total) is often called a “paradise built on earth.” Its name means “Abode of Love,” and contemporary accounts praise it as the pinnacle of Mughal horticulture. Shalimar’s symmetry (three terraces descending to a basin) and use of flowing water exemplify the charbagh ideal. Many Mughal forts (e.g. Agra Fort’s Anguri Bagh) and palaces incorporated gardens as integral courtyards. Collectively, these gardens were microcosms of Mughal ideology: they demonstrated mastery over nature, fulfilled spiritual ideals of paradise, and provided refreshing retreats in the Indian climate.

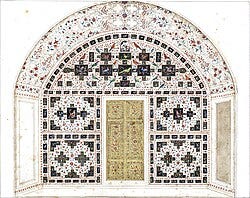

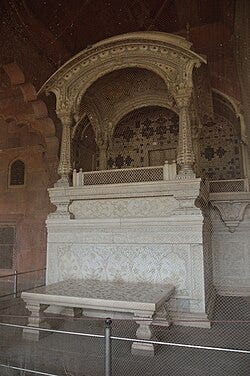

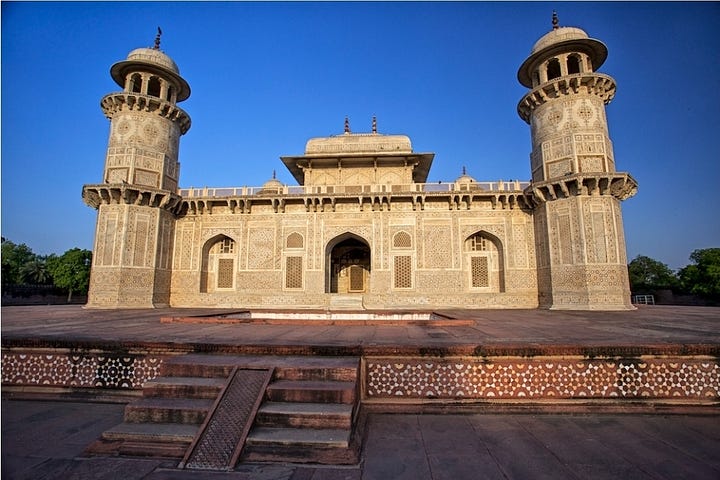

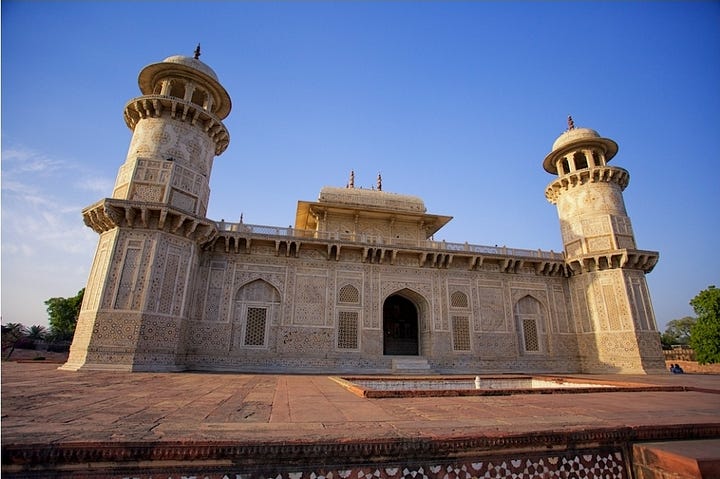

One of the most luxurious Mughal decorative arts is pietra dura; the inlay of cut precious and semi-precious stones into marble surfaces. Imported from Italy and Persia, it became known in India as parchin kari (literally “driven-in work”). The technique reached its apogee under Shah Jahan. The Taj Mahal is its supreme showcase: the mausoleum’s arched panels, cenotaph chamber and cenotaph are covered with arabesque motifs of flowers and calligraphy executed in lapis lazuli, jade, agate, and other hardstones inlaid into the white marble walls. Each flower is carved from a different stone, carefully fitted and polished to a seamless finish. A survey of the work notes that Mughal artisans “affectionately” called this craft parchin kari, and the Taj stands as its “most sumptuous expression” in India.

This parchin kari technique exemplifies Mughal craftsmen’s skill in combining diverse materials into harmonious patterns. The pietra dura technique was applied to many Mughal structures. The tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulah (Agra, 1628–1631), often called the “Baby Taj”, features extensive geometric and floral inlays, setting a precedent for Shah Jahan’s works. Even secular halls at the Red Fort (e.g. the Rang Mahal) have pilasters and pavilions crowned with inlaid stone medallions. The artisanship was painstaking: stones were grooved on the back, fitted like a puzzle, and fixed into grooves on a marble base, creating flat, smooth panels. The inlay work served both aesthetic and symbolic purposes: the lustrous stones contrast with the marble to create “jewel-box” interiors, while the floral motifs evoke paradise. European travelers were dazzled by the effect; likening the interiors to “painted enamel.” Today, Mughal pietra dura remains a benchmark of premodern lapidary art, and the Taj’s flower panels have inspired later artisans in Rajasthan’s parchin kari workshops.

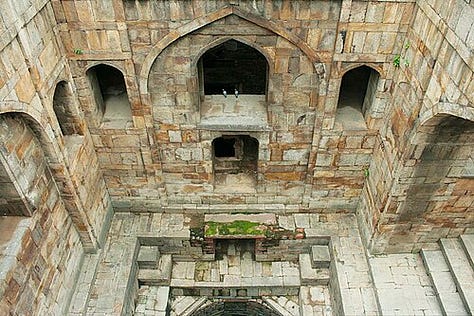

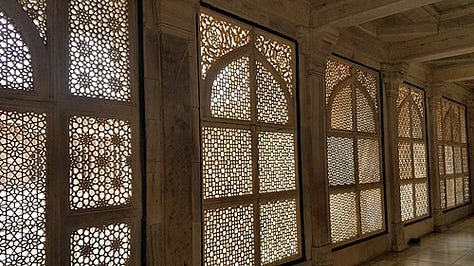

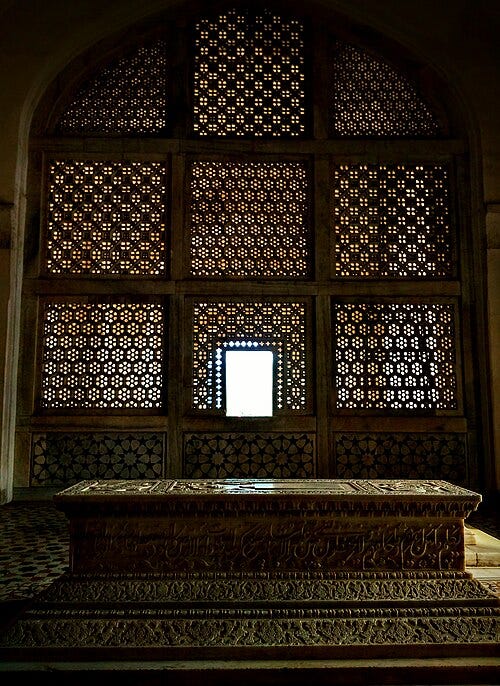

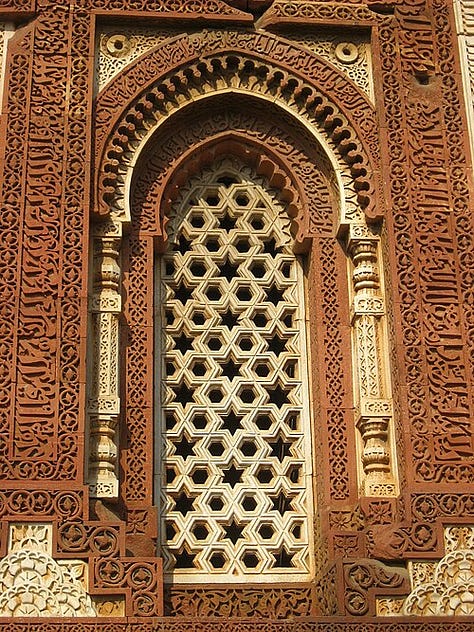

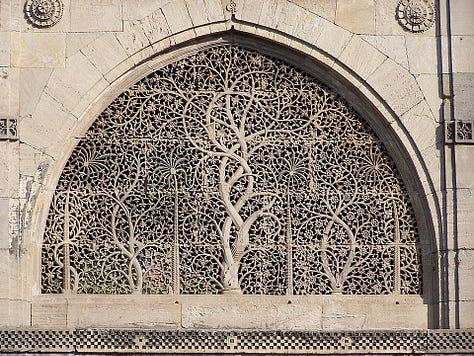

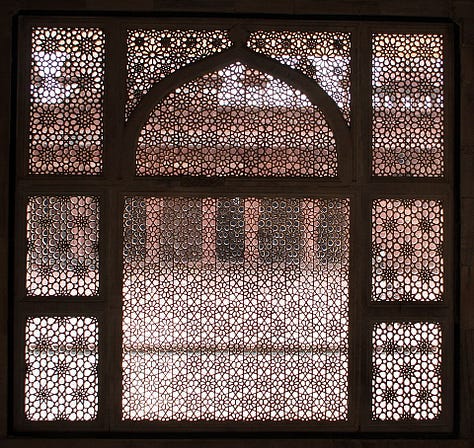

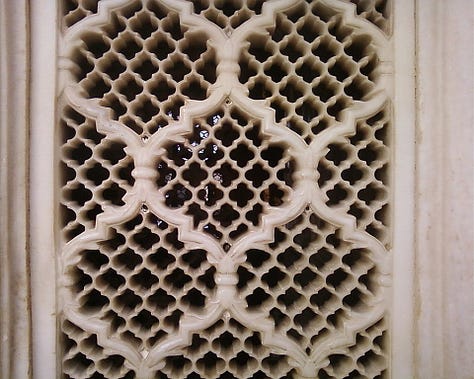

The Mughals employed jali (stone lattice) screens as both ornament and utilitarian feature. These perforated stone panels, carved from sandstone or marble, display incredibly intricate geometric or floral patterns. Jalis were used to enclose windows, balconies, and prayer niches. A famous example is the “Tree of Life” jali in the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque (Ahmedabad), though Mughal structures also feature elegant jalis. The lattice serves a practical function: it allows light and air to filter into interior spaces while maintaining privacy and reducing heat. In a hot climate, the small openings diffuse harsh sunlight into a soft glow and channel breezes through narrow vents, effectively cooling rooms. From inside, one can see out through the myriad holes, but from outside the interior is obscured by glare; thus jalis elegantly enforce privacy; crucial in palaces and harem quarters.

Artistically, jali screens are a hallmark of Indo-Islamic design. Under the Mughals the carving reached new refinement; geometric patterns gave way to stylized vegetal motifs and star patterns rendered at sub-millimeter scale. Their precise repetition of forms creates a play of light and shadow that animates walls throughout the day. For example, the jali at Akbar’s tomb in Agra (1605) features ornate arabesque vines, and the screen in the Pearl Mosque (Jahaz Mahal) in Delhi echoes Mughal gardens. A DailyArt article observes that jalis “added artistic flair to the magnificent architectural wonders of this era” while serving practical purposes – they “allow[ed] for the circulation of air, shelter from direct sunlight, as well as privacy.”. In addition, scholars note the jali’s climate-engineering: each small hole acts like a cubical aperture that cuts solar ingress and increases airflow (applying Bernoulli and Venturi principles). In essence, Mughal jali screens are masterpieces of secular sculpture, almost lace-like in solidity, that demonstrate how the empire combined science, art and luxury. From Taj Mahal chambers to Red Fort pavilions, the latticed screens remain iconic to the Mughal aesthetic, their beautifully perforated surfaces carving interior spaces into jewel-like sanctuaries of diffused light.

References:

Artsy. Astounding Miniature Paintings of India’s Mughal Empire. Artsy, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-astounding-miniature-paintings-indias-mughal-empire. Accessed 19 March 2025.

Guardian. Creative Sparks: How the Mughal Empire Made Opulent Art with Power. The Guardian, 14 Nov. 2024, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/nov/14/great-mughals-exhibition-v-and-a-south-kensington. Accessed 19 March 2025.

Walters Art Museum. Baburnama by Babur, Emperor of Hindustan. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W596/images/W596_0001_Q.jpg. Accessed 19 March 2025.

Victoria and Albert Museum. The Arts of the Mughal Empire. V&A Museum, 2016, www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-arts-of-the-mughal-empire. Accessed 19 March 2025.

DailyArt Magazine. Tola, Maya M. Jali in Mughal Architecture, the Most Delicate Stone Curtains. DailyArt, 18 Apr. 2023, www.dailyartmagazine.com/jali-in-mughal-architecture-the-most-delicate-stone-curtains/. Accessed 19 March 2025.

DailyArt Magazine. The Miniature Paintings of the Mughal Empire. DailyArt, www.dailyartmagazine.com/mughal-miniature-paintings/. Accessed 19 March 2025.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi. UNESCO, whc.unesco.org/en/list/232. Accessed 19 March 2025.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Fatehpur Sikri. UNESCO, whc.unesco.org/en/list/255. Accessed 19 March 2025.

Archnet. The Parchin Kari Programme at the Taj Mahal. Archnet Islamic Architecture Project, vol.1, no.1, 2014, archnet.org/library/documents/one-document.tcl?document_id=10070. Accessed 19 March 2025.

What an extraordinary pictorial and information journey through Mughal architecture! The photographs are dense with style and beauty, and your descriptions of how the minatures transformed with colour, technique and style over time is fascinating!