Baroque Optics and Jesuit Ideology: The Theatrics of The Glorification of Saint Ignatius

#FrescoFriday

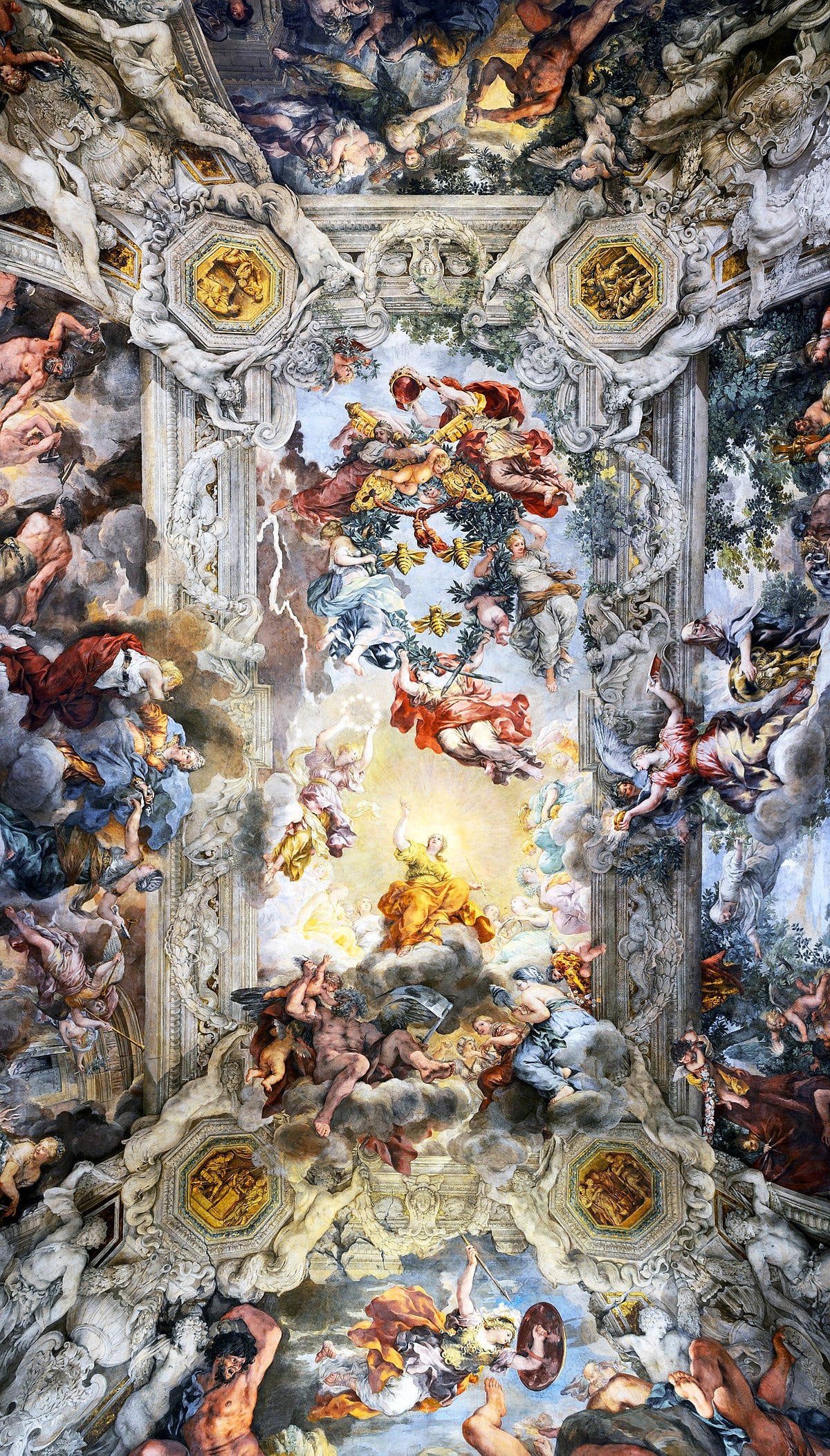

Andrea Pozzo’s The Glorification of Saint Ignatius (1691) is far more than an awe-inspiring ceiling fresco; it is a dynamic visual manifesto of Jesuit evangelism and Counter-Reformation ingenuity. Located in Rome’s Church of Sant’Ignazio, the work weaves together art, theology, and scientific precision to create a transcendental experience. Through a masterful blend of quadratura and single-point perspective, Pozzo not only dissolves the boundaries between the earthly and the divine but also reaffirms the power of visual rhetoric in instilling spiritual awe.

Commissioned during a period of intense religious restructuring, The Glorification of Saint Ignatius was conceived amid the Catholic Church’s desperate efforts to reassert its authority after the Protestant Reformation. In the wake of doctrinal challenges, the Jesuit Order embraced art as an essential tool for propaganda and spiritual renewal. The Church of Sant’Ignazio, dedicated to Ignatius of Loyola, the order’s founder, was envisioned as a monumental embodiment of Jesuit ideals. Originally part of a larger architectural project initiated under Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi in the early 17th century, financial and structural constraints ultimately led to a painted dome substitute (Harris and Zucker). This innovative solution not only reflected the Jesuits’ resourcefulness but also symbolized their commitment to a visual theology that could reach a mass audience.

The fresco emerged during a time of global Jesuit missionary campaigns. As Jesuits spread Catholicism "to the four corners of the world," the work’s celestial imagery functioned as both a spiritual beacon and an ideological statement. The illuminated narrative, where divine radiance channels from Christ to Ignatius, reinforced the notion that salvation, ignited by Jesuit zeal, had universal reach. The integration of art and evangelism in this fresco, therefore, became a critical part of the Counter-Reformation’s strategy (Wittkower 127).

At the core of Pozzo’s work is an almost obsessive commitment to perspective. In The Glorification of Saint Ignatius, a bronze disk fixed in the nave designates the singular vantage point from which the illusion works perfectly. From this “determinant point,” painted architectural elements (columns, arches, and coffered ceilings) seamlessly extend into an imagined, infinite space. Pozzo’s painstaking methodology involved using a 4-foot wooden model of the nave, a grid system, and precisely aligned threads and lamps to transfer geometric rigor onto the vault (Racioppi). This systematic approach is documented in his treatise, Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum (1693), in which he insists that perspective should “seem real from one determinant point only.” Such technical precision not only demonstrates a scientific understanding of optical phenomena but also transforms the fresco into a “ladder to heaven”; a metaphor for both physical ascent and spiritual renewal (Harris and Zucker).

Beyond its geometric mastery, the composition is a carefully choreographed spatial drama. Figures recede into the distance, diminishing in scale and intensifying the sensation of vertical expansion. Angels and saints spiral upward in rhythmic motion, their forms emphasized by pronounced chiaroscuro that lends them a sculptural quality against the painted void. This interplay between light and shadow, combined with a dynamic placement of figures, orchestrates an immersive narrative that is as mathematical as it is mystical (Crowe).

Every symbol and allegory in the fresco serves to reinforce Jesuit doctrine and Counter-Reformation priorities. At its center, Christ directs a luminous beam toward St. Ignatius, who is depicted in a humble posture of devotion. This divine light, signifying grace and the transmission of authority, symbolizes the Jesuit mission to channel the essence of Catholic salvation throughout the globe. The Holy Spirit, represented as a dove, and God the Father complete the Trinitarian motif, reminding viewers of core ecclesiastical tenets while visually affirming the Catholic hierarchy.

Further enriching this iconographic program are allegorical depictions of the four continents, personified as female figures paired with symbolic animals (drawn from Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia, 1593). These images not only celebrate the universality of Jesuit outreach but also subtly map the global ambitions of the Order. Flames bordering the composition evoke the Latin root of Ignatius’s name (“ignis” meaning fire) and connect to biblical passages (cf. Luke 12:49) that are interpreted as divine impetus to “ignite” the world with Catholic fervor. Clouded vignettes featuring noted missionaries, such as Francis Xavier, further sanctify these global endeavors, positioning Rome as the epicenter of spiritual illumination (Tate Modern).

Since its unveiling, The Glorification of Saint Ignatius has been hailed as one of the crowning achievements of Baroque illusionism. Contemporary art historians praise its dual function: as a technical marvel that redefined the spatial parameters of ceiling painting and as a potent embodiment of Jesuit ideology. Marcello Fagiolo has observed that the “exaltation of fire” in Pozzo’s work encapsulates both the fervor of spiritual aspiration and the dramatic tension of religious propaganda (Fagiolo 91). Comparisons to masterpieces such as Correggio’s Assumption of the Virgin and Pietro da Cortona’s expansive ceilings underscore Pozzo’s innovative synthesis of architectural illusion and theological narrative.

Pozzo’s influence extended well beyond his lifetime. His treatise became a foundational text for architects and painters across Europe; impacting figures like Christopher Wren and inspiring the illusionistic treatments seen in later Rococo and Neoclassical works. Today, the Church of Sant’Ignazio attracts over 500,000 visitors annually, a testament to the enduring power of Pozzo’s visual language. The fresco continues to serve as a touchstone in scholarly debates about the interplay of art, science, and ideology, illustrating how technical mastery can serve as a vehicle for religious and political persuasion (Wittkower 134).

In The Glorification of Saint Ignatius, Andrea Pozzo masterfully fuses scientific precision, artistic innovation, and potent theological symbolism to create a work that is both a devotional image and a geopolitical statement. His calculated use of perspective transforms the physical confines of Sant’Ignazio into a celestial theater, inviting viewers to participate in a transcendent journey. As a pinnacle of Baroque art and Jesuit propaganda, the fresco remains an enduring symbol of the Counter-Reformation’s ambition; a radiant confluence of art, faith, and reason that continues to inspire and provoke scholarly inquiry.

References:

Crowe, Jonathan. Andrea Pozzo and the Mysticism of Illusory Space. The Art Bulletin, vol. 82, no. 2, June 2000, pp. 234–253.

Fagiolo, Marcello. Exaltation of Fire: Illumination and Ideology in Baroque Ceiling Painting. Journal of Baroque Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, pp. 89–102.

Harris, Beth, and Steven Zucker. Andrea Pozzo, Glorification of Saint Ignatius. Smarthistory, 9 Dec. 2015, https://smarthistory.org/fra-andrea-pozzo-glorification-of-saint-ignatius/.

Racioppi, Pier Paolo. Church of St. Ignatius, Triumph of Saint Ignatius Ceiling Fresco. Discover Baroque Art, Museum With No Frontiers, 2025, https://baroqueart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;BAR;it;Mon11;32;en.

Tate Modern. Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational Disability Art. 2023.

Wittkower, Rudolf. Art and Architecture in Italy, 1600-1750. Penguin Books, 1999.

Pozzo, Andrea. Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, www.oxfordartonline.com. Accessed 28 Jan. 2025.

Brilliant! Many thanks!

I had the opportunity to see Andrea Pozzo’s The Glorification of Saint Ignatius in person in 2003. If you are ever in Rome and it’s available for a tour I highly recommend it. We spent more time looking at this than the Sistine Chapel, and it had 1/10th the number of visitors. The photos are great but seeing the actual work is for lack of a better term, a bit mind blowing.