Sylvester Stallone is widely known as a cinematic icon, the embodiment of the underdog and the action hero, thanks to legendary roles like Rocky Balboa and John Rambo. Yet beyond his powerful screen presence and storytelling, Stallone is also a prolific visual artist, whose expressive paintings have found an international audience and earned critical reassessment in recent years. His creative duality, actor, director, and writer on one hand; painter on the other, reveals an ongoing quest for authenticity and a profound need to process trauma, hope, and selfhood through both image and word. Stallone’s artistic achievements are not merely a sidebar to his fame but represent an integral, often overlooked, facet of his lifelong struggle for meaning and personal expression (Farago; “The Art of Sylvester Stallone”).

Sylvester Gardenzio Stallone was born July 6, 1946, in the gritty Hell’s Kitchen district of Manhattan, New York City, to Francesco “Frank” Stallone Sr., a hairdresser and polo enthusiast, and Jacqueline “Jackie” Stallone, an astrologer and women’s wrestling promoter (“Sylvester Stallone,” Encyclopedia Britannica). Birth complications involving forceps left the left side of his face partially paralyzed, resulting in his now-famous slurred speech and brooding expression (Kobal 15–18). These early adversities, coupled with frequent moves and bullying in his youth, deeply influenced Stallone’s fascination with resilience and self-transformation; a theme running through both his films and paintings (Farago).

Stallone spent his formative years between New York and Silver Spring, Maryland. He attended Devereux Manor High School, an institution for troubled youths, and later the American College of Switzerland before studying drama at the University of Miami. Facing years of rejection as a struggling actor in New York City, Stallone took on a string of menial jobs and bit parts in films, including Woody Allen’s Bananas (1971) and the adult feature The Party at Kitty and Stud’s (1970), later marketed as Italian Stallion (Kobal 33–38). Despite these setbacks, he began painting seriously as a form of emotional release and introspection, a habit that would persist through his entire life (“The Art of Sylvester Stallone”).

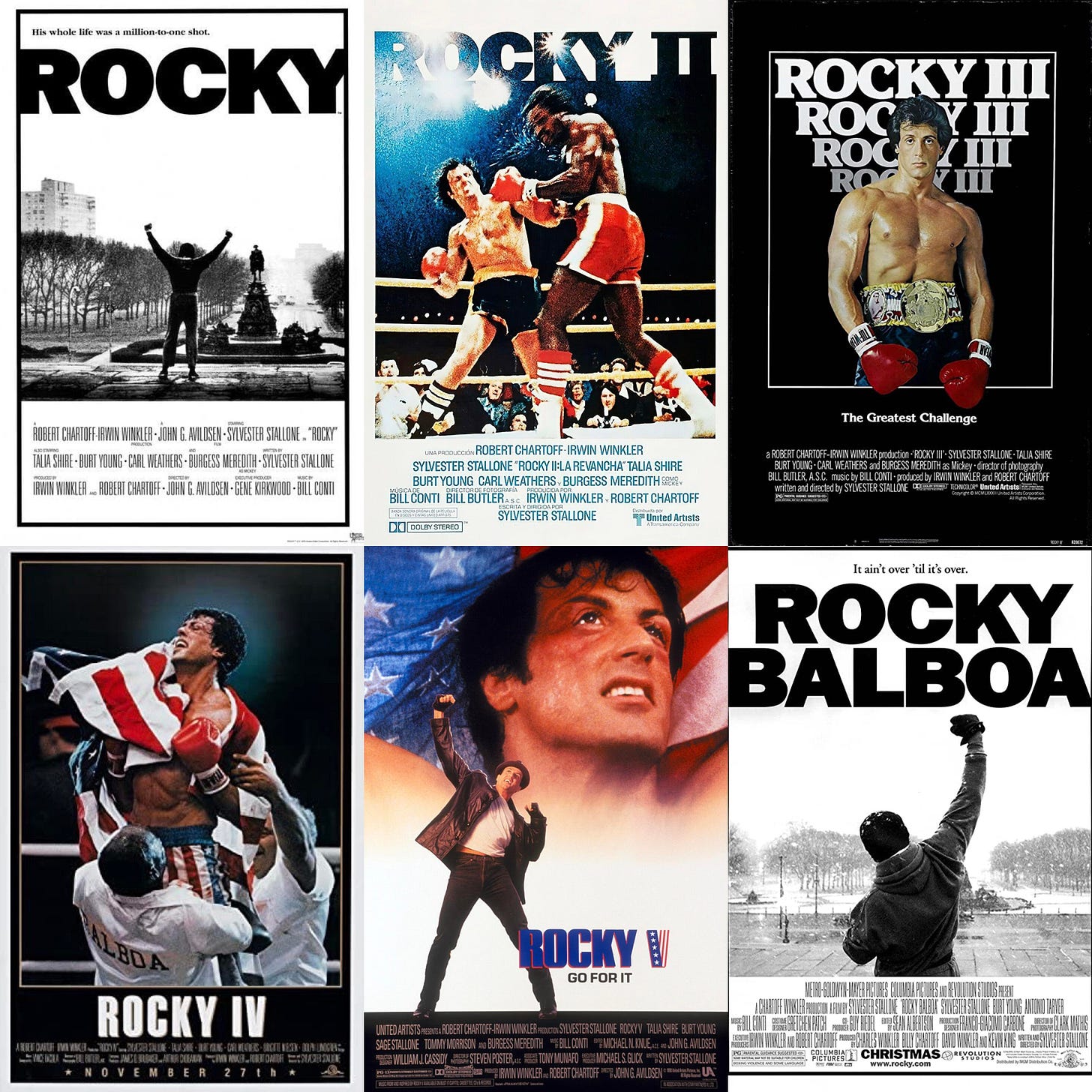

Stallone’s breakthrough came in 1976 with Rocky, a film he wrote over a furious three-day stretch inspired by the Muhammad Ali–Chuck Wepner fight. He famously refused to sell his script unless he could star as the lead, Rocky Balboa; a move that risked his career but paid off in spectacular fashion. Rocky received ten Academy Award nominations and won Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Film Editing. Stallone’s performance earned him Oscar nominations for both acting and writing, a rare achievement only matched at the time by Charlie Chaplin and Orson Welles (Dirks; “Sylvester Stallone,” Britannica).

The Rocky franchise would span eight films (1976–2023), evolving from the story of an underdog boxer into a complex meditation on perseverance, failure, and redemption. Stallone directed Rocky II (1979), Rocky III (1982), Rocky IV (1985), and Rocky Balboa (2006), all of which explored shifting political and personal landscapes (Tasker 115–18). In 2015, Stallone returned as an aging Rocky in Ryan Coogler’s Creed, earning renewed critical acclaim and an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor (Lumenick).

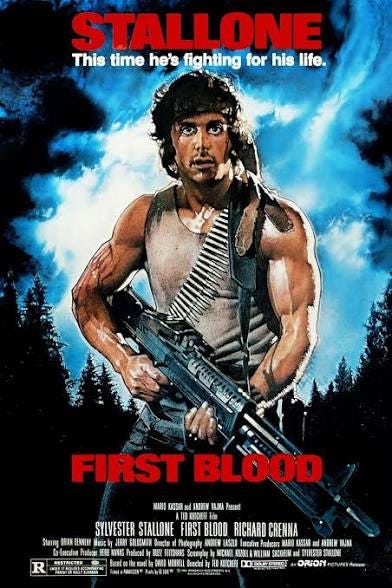

In parallel, Stallone developed the character of John Rambo in First Blood (1982), based on David Morrell’s novel. The Rambo series, which now spans five films, solidified Stallone’s image as a muscular action hero while offering a critique of post-Vietnam trauma and American militarism (Tasker 98–108; “Sylvester Stallone,” Britannica). Films like Cobra (1986), Cliffhanger (1993), and Demolition Man (1993) showcased his ability to reinvent the action genre, often blending violence with self-aware humor.

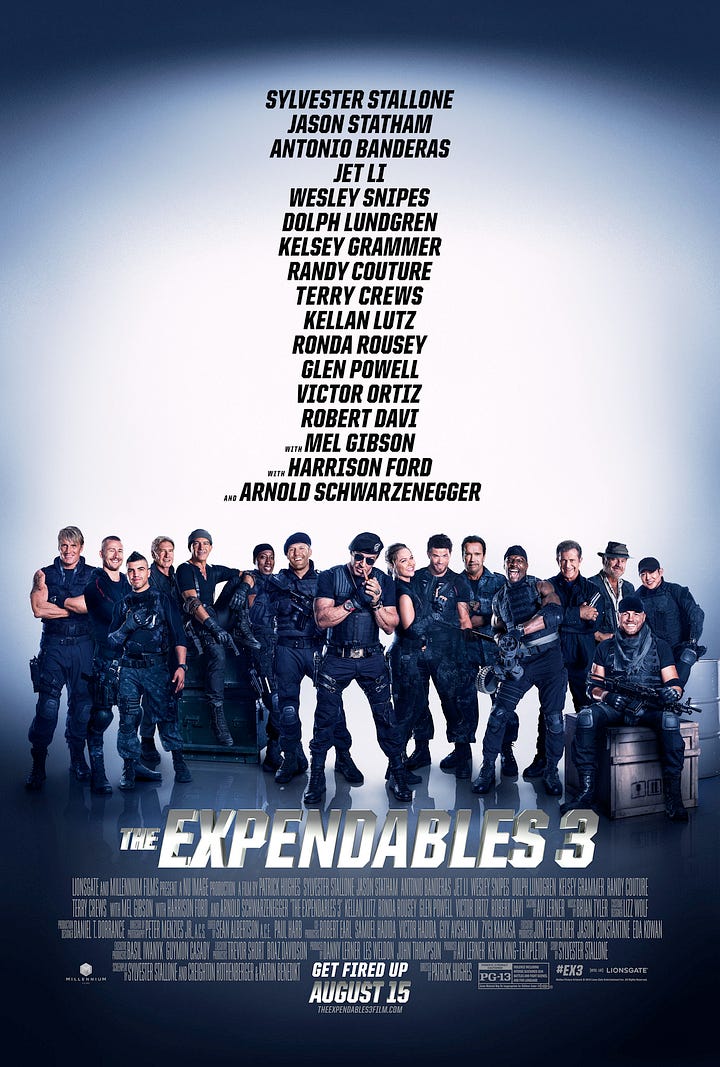

Not all of Stallone’s cinematic projects succeeded, comedies such as Oscar (1991) and Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot (1992) were critical failures, but his resilience in the face of professional and personal adversity has remained a central part of his public persona (Kobal 128–30; Lumenick). In 2010, he launched The Expendables, an ensemble franchise featuring action stars of the 1980s and 1990s, writing, directing, and starring in the first film and contributing to its sequels (Dirks).

Stallone’s career is distinguished by his dogged pursuit of creative control, his willingness to parody himself, and his ability to continually reinvent his public image. As critic Jason Farago observes, Stallone’s “screen personas and painted figures reflect not only the fighter’s pain but the artist’s vulnerability” (Farago).

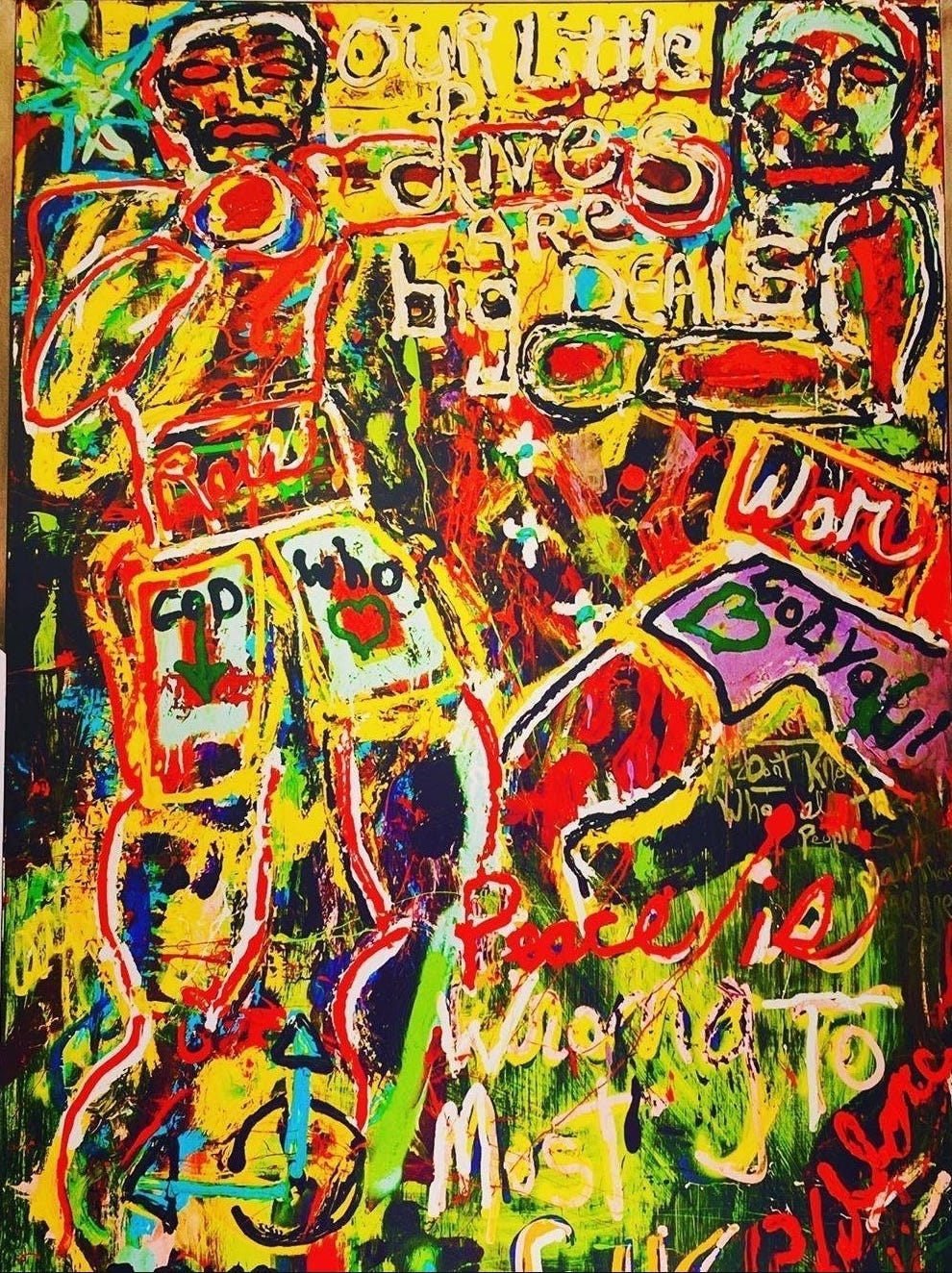

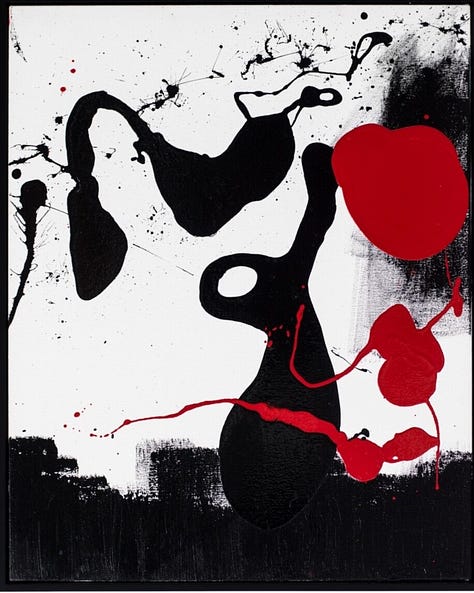

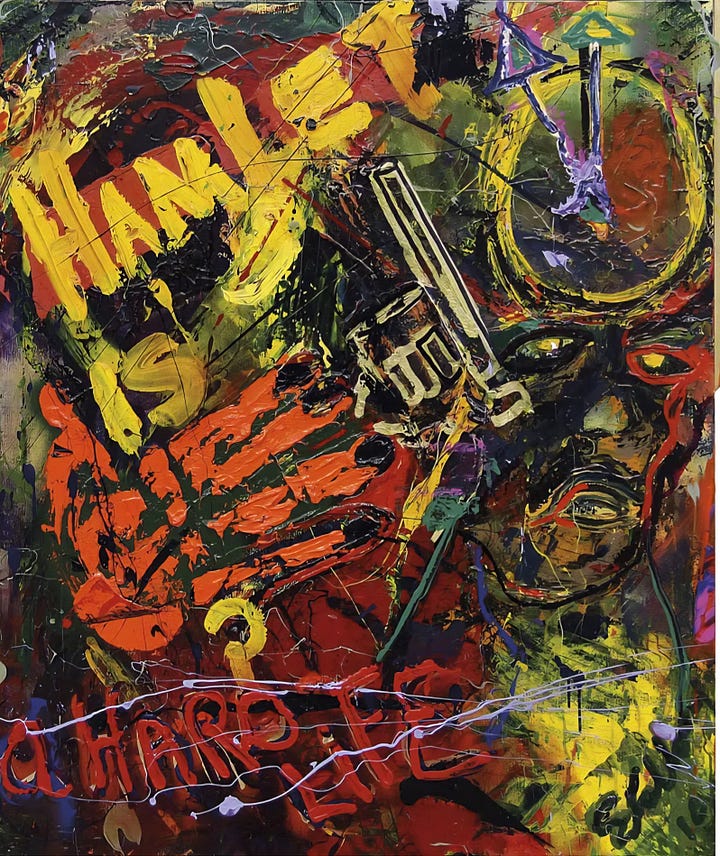

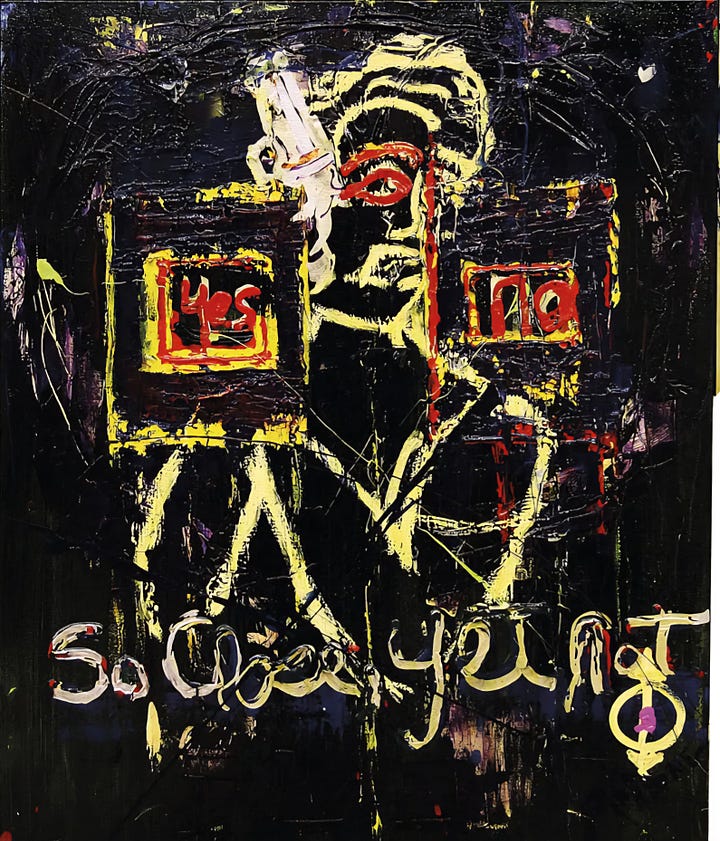

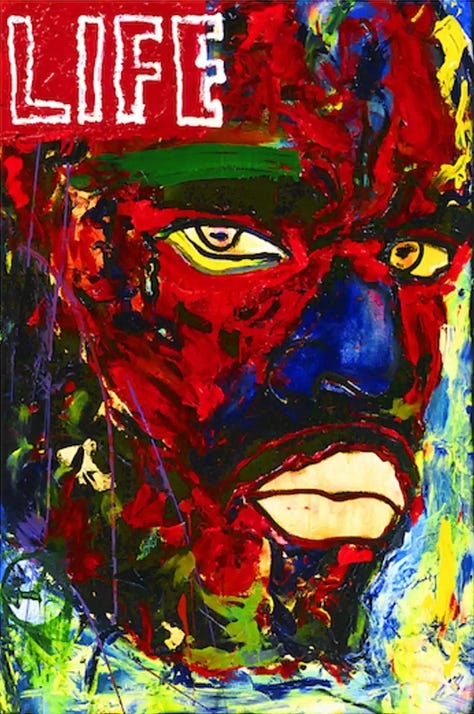

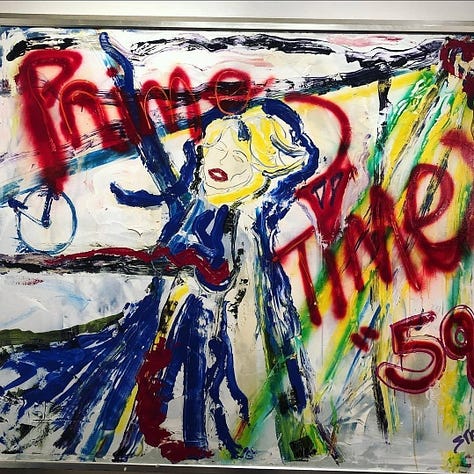

Stallone’s art, though long a private pursuit, has in recent years become a significant part of his public legacy. He began painting as a teenager and often worked on canvases between acting jobs, using the medium to work through personal crises, loss, and the pressures of fame (“Sylvester Stallone: Painting. From 1975 Until Today”; Farago). Stallone’s visual style is frequently described as neo-expressionist, drawing influence from Jean-Michel Basquiat, Willem de Kooning, and Francis Bacon, all of whom valued emotional immediacy and rawness over technical polish (Farago; “The Art of Sylvester Stallone,” Galerie Contemporaine).

His paintings are often large-scale and intensely colored, featuring bold brushstrokes, distorted figures, and recurring themes of violence, struggle, and celebrity. Stallone sees painting as a parallel creative process to screenwriting and acting, stating, “If I had chosen painting over acting, I would’ve been happier. It’s much more personal and I’m the creator. Whereas, in film, you’re always a bit at the mercy of fate and circumstance” (Stallone, qtd. in Farago).

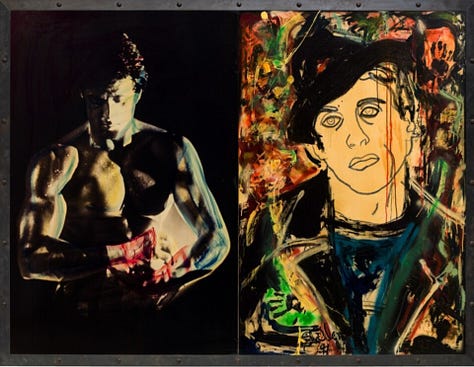

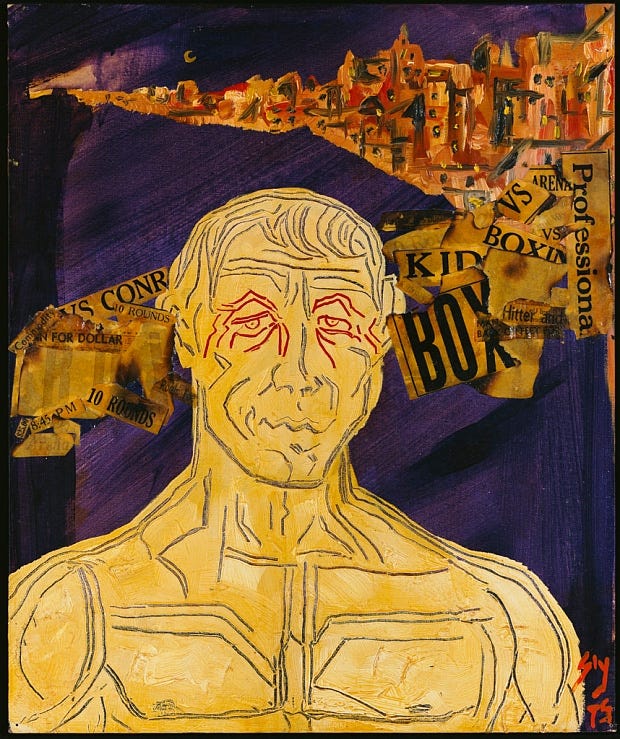

Stallone’s first major exhibition, “Sylvester Stallone: Art. 1975–2013,” was held at the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg in 2013, featuring over thirty paintings and drawings from four decades (“Sylvester Stallone’s Paintings Go on Show in Russia,” The Guardian). The show included “Finding Rocky” (1975), a semi-abstract self-portrait painted before he wrote the screenplay for Rocky, and “Rambo” (2013), a colorful, anguished figure based on his film character. Both pieces have been widely reproduced and are recognized as foundational to Stallone’s art (“The Art of Sylvester Stallone,” Galerie Contemporaine).

In 2015, the Galerie Contemporaine in Nice, France, hosted another major retrospective, including the painting “Self-Portrait” (2015), which juxtaposes the iconography of Rocky and Rambo with graffiti-like text and gestural abstraction. In 2021, the Osthaus Museum in Hagen, Germany, mounted “Sylvester Stallone: The Magic of Being,” featuring 50 paintings spanning his entire career and focusing on the existential themes that unite his films and art (Farago; “Sylvester Stallone Exhibits His Art in Germany,” Artnet News).

While initially dismissed by some as “celebrity art,” Stallone’s paintings have gained respect for their authenticity, technical ambition, and emotional intensity. Critics now recognize his ability to channel the same vulnerability and aggression that define his screen roles into his canvases. Jason Farago of The New York Times notes that Stallone’s “paintings are not vanity projects but haunted, confessional explorations of masculinity, grief, and public life” (Farago).

Stallone’s art is also deeply autobiographical. Many works feature self-portraits or deconstructed references to Rocky and Rambo, exploring the complex interplay between his public and private identities. The recurring motifs of battle, scars, and masks reveal a persistent preoccupation with survival; psychological as much as physical (Farago; “Sylvester Stallone: The Magic of Being,” Osthaus Museum).

Stallone himself has said, “For me, painting is the purest form of self-expression. It is an uncensored dialogue with myself; a way to work through everything I can’t say on camera or in interviews” (Stallone, qtd. in “The Art of Sylvester Stallone,” Galerie Contemporaine).

Sylvester Stallone’s life and art are inseparable stories of struggle, reinvention, and relentless self-inquiry. From his origins in a tumultuous New York childhood to his ascent as one of Hollywood’s most enduring icons, Stallone has never ceased to search for new ways to communicate the pain and hope of the human condition. Whether battling for respect in the ring, surviving on the battlefield, or laying bare his soul on canvas, Stallone’s creativity remains urgent, visceral, and profoundly personal. His paintings, no less than his films, demand to be seen as part of the same fight: to claim one’s place, voice, and truth in a world too often eager to look away.

References:

Dirks, Tim. Rocky (1976). Greatest Films, filmsite.org, https://www.filmsite.org/rocky.html.

Farago, Jason. Sylvester Stallone, Painter. The New York Times, 22 May 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/22/arts/design/sylvester-stallone-paintings.html.

Kobal, John. Sylvester Stallone: A Star Is Born. Doubleday, 1978.

Lumenick, Lou. Stallone: The Comeback King. New York Post, 28 Feb. 2016, https://nypost.com/2016/02/28/sylvester-stallone-the-comeback-king/.

Sylvester Stallone. Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sylvester-Stallone.

Sylvester Stallone’s Paintings Go on Show in Russia. The Guardian, 27 October 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2013/oct/27/sylvester-stallone-paintings-russian-state-museum.

Tasker, Yvonne. Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and the Action Cinema. Routledge, 1993.

The Art of Sylvester Stallone. Galerie Contemporaine, 2015, https://galerie-contemporaine.com/en/artistes/sylvester-stallone.

Sylvester Stallone Exhibits His Art in Germany. Artnet News, 4 December 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/sylvester-stallone-osthaus-museum-2047008.

Sylvester Stallone: The Magic of Being. Osthaus Museum Hagen, 2021, https://www.osthausmuseum.de/index.php?seite=ausstellungen_detail&ausID=445.

An unexpected trip down several strands of memory lane in this one! Personally understanding the struggles of growing up in NYC’s tough neighborhoods, and for Stallone in particular, Hell’s Kitchen—becomes the even lower platform from which to reach for heights everyone says are not possible. Yet you do it anyway, and win.

So why did I run up the ‘Rocky Stairs’ in 2015? My girlfriend and I turned 50 the same year. Our birthdays are very close in time, so we usually celebrate in some way together. We have been friends since we were 5 years old, through thick and thin. She decided to have her birthday weekend in Philly, so we all flew or drove in to co-celebrate. What I expected was a big ass long table in an old-school Italian style restaurant downtown with lots of family and stories and amazing platters of calamari and parmigiana floating around tables. What I didn’t know is her twin sisters had a boom box and an agenda afterwards: For us to all go over to those famous stairs, hit play and take off up them (on full stomachs, of course!)

We birthday girls led the way. I have to say it was not an easy run but the music definitely helped. We had reached a point in our lives and our friendship when that run felt more necessary than I could have imagined. We laughed and cried all the way.

When we got to the top? Of course we held our arms high, hands clasped and jumped up and down. The victory we had won over Time tasted quite sweet.

So there we have it: My Rocky Balboa story.

Fascinating, and so well written, as usual, rogue!