Félix González-Torres was born on November 26, 1957, in Guáimaro, Cuba, and in 1968 was sent to Madrid and later Puerto Rico under a Cuban government program for children abroad (Museum of Modern Art). He enrolled at the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan (1975–79), then relocated to New York City in 1979 on scholarship to study photography at Pratt Institute, earning his BFA in 1983, and went on to receive an MFA from the International Center of Photography and New York University in 1987 (Museum of Modern Art). During these formative years, González-Torres joined the politically engaged collective Group Material (1979–96), whose activism around feminism, civil rights, and gay rights profoundly shaped his integration of minimalist form with social critique (Zeller 102).

González-Torres’s practice synthesizes the reductive rigor of Minimalism, as exemplified by Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt, with Conceptual art’s privileging of idea over object (Judd 74; LeWitt 80). His installations anticipate relational aesthetics: each work generates social exchanges, viewers share candies, remove sheets, observe drifting clocks, thereby making the audience co-creators of meaning (Bourriaud 38). Moreover, his engagement with critical theory, from Roland Barthes’s notions of punctum to Judith Butler’s theories of performativity, underpinned his strategy of destabilizing fixed identity categories through participatory gestures (Barthes 28; Butler 142).

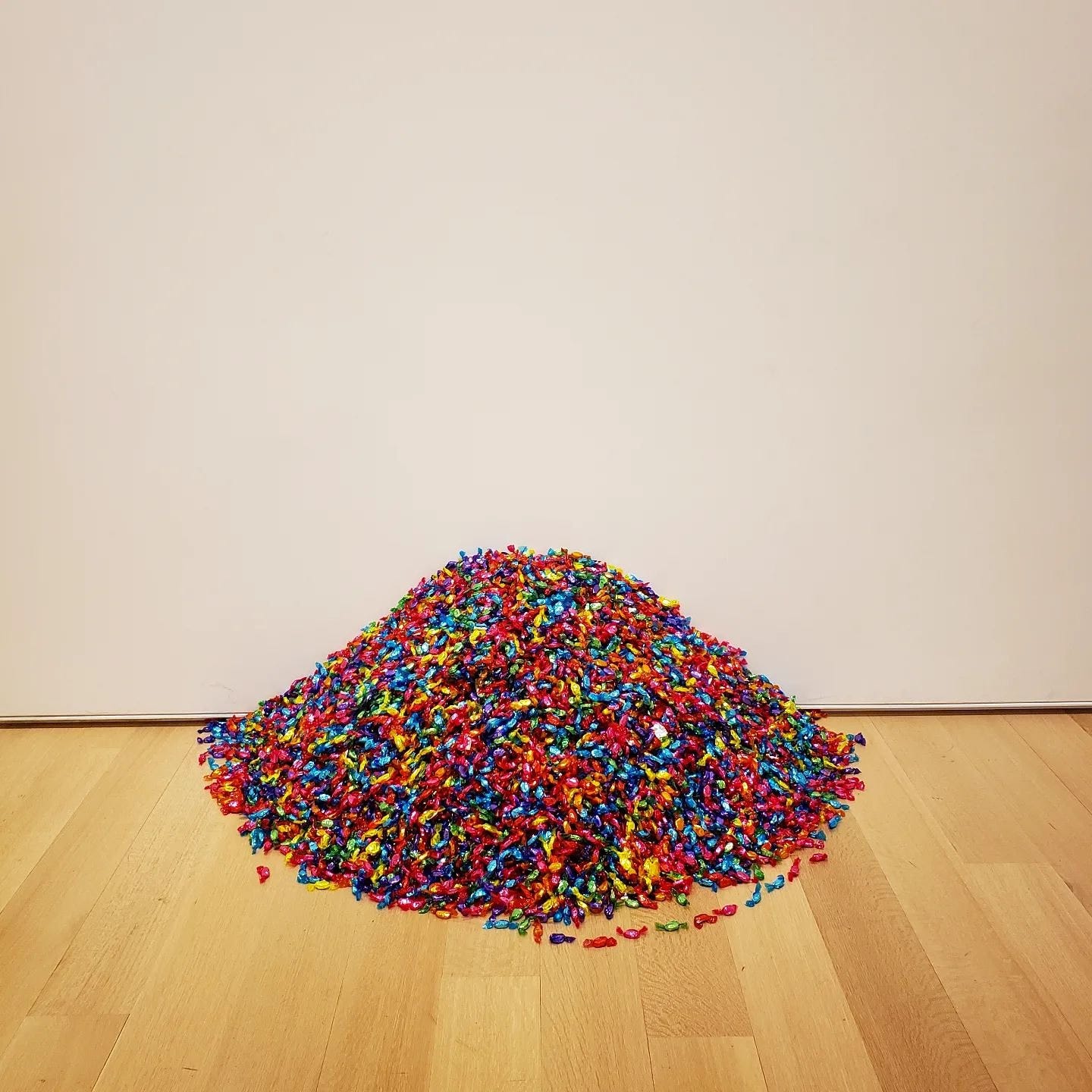

From 1989 to 1995 González-Torres developed a series of “Untitled” works that transformed gallery spaces into sites of collective ritual and remembrance. In 1991, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) presented a 175-pound mound of cellophane-wrapped candies from which visitors freely took pieces, enacting the gradual disappearance, and potential renewal, of his partner Ross Laycock to AIDS (Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Modern Art). That same year, “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) consisted of two identical wall clocks synchronized at installation; over time their subtle mechanical drift dramatized intimacy’s fragility and the inexorable passage of time (Tate; Museum of Modern Art). Also in 1991, “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform) invited visitors onto a low mirrored platform, collapsing the divide between spectator and spectacle and celebrating participatory joy (Dia Art Foundation).

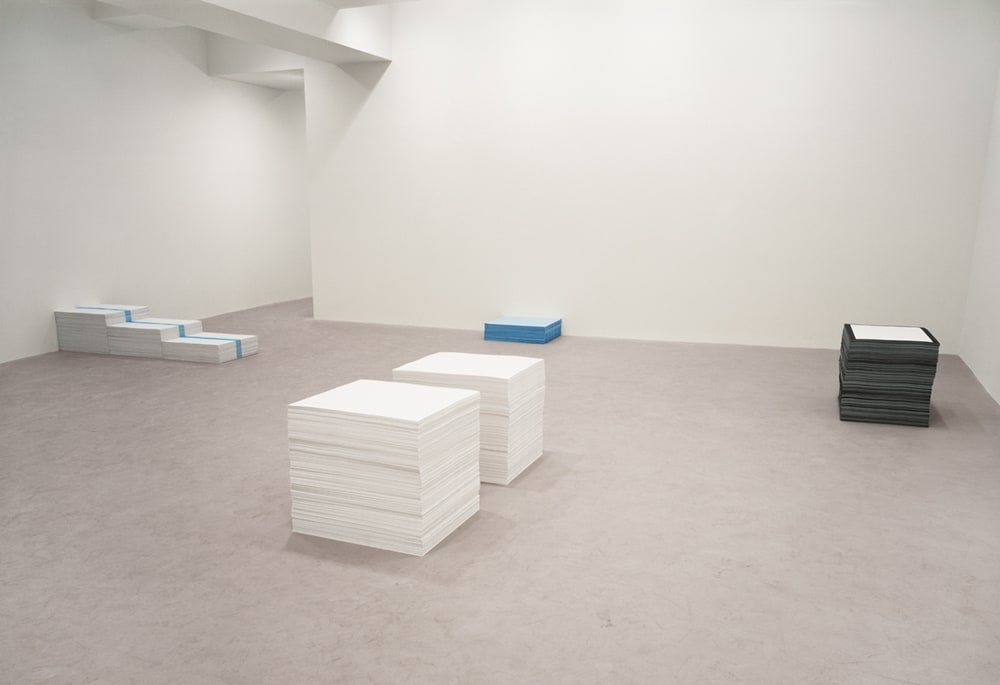

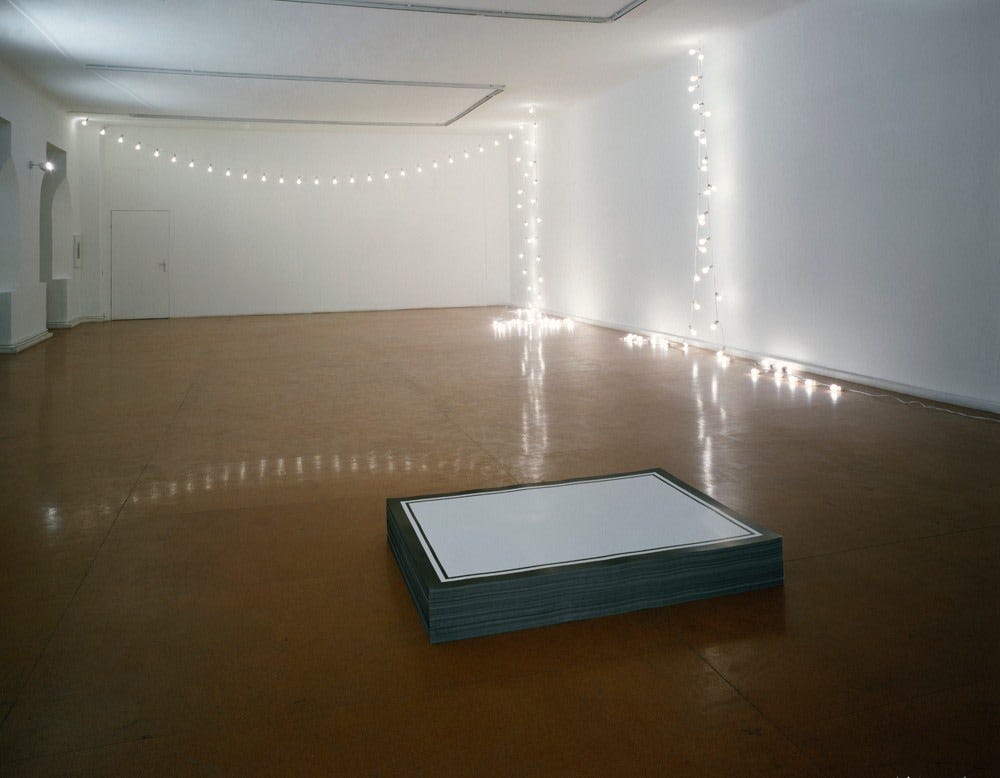

González-Torres’s Paper “Stacks” (1989–95) comprised modular piles of blank or minimally printed sheets, photographs, texts, or diagrams, each removal by a viewer activating communal authorship and underscoring impermanence (“Félix González-Torres,” Wikipedia). His Light String installations (1992–94) featured bare bulbs strung across walls or ceilings, their flicker and occasional burnout evoking both technological fragility and the precariousness of queer lives amid the AIDS epidemic (Dia Art Foundation; Crimp 73).

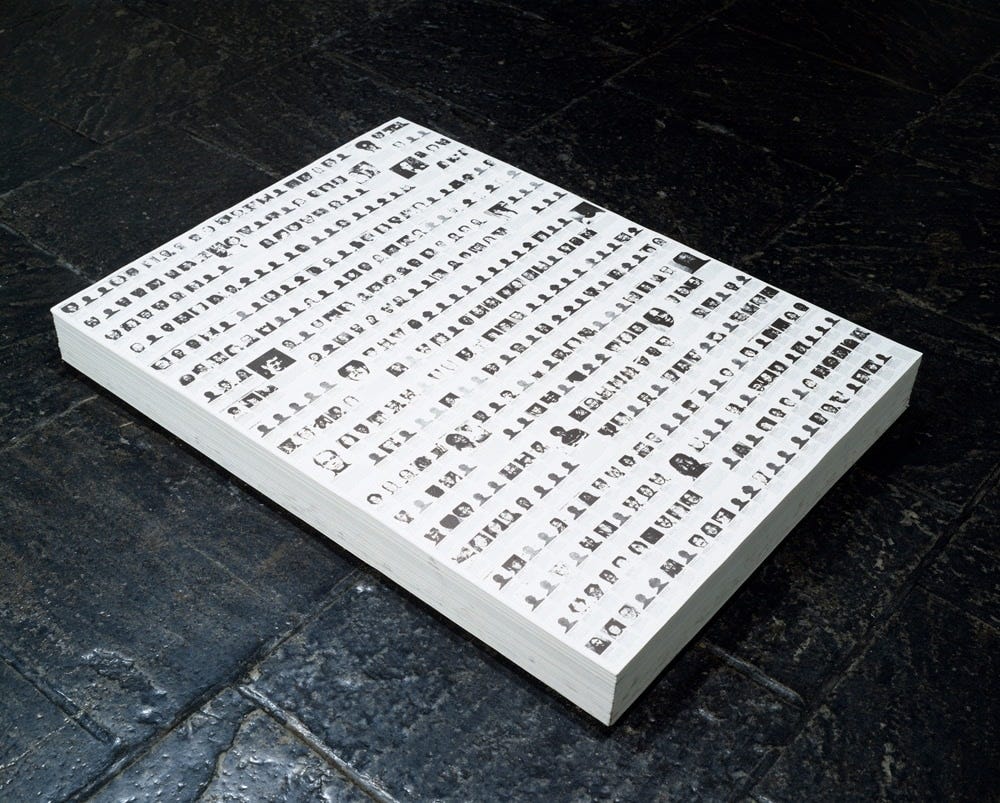

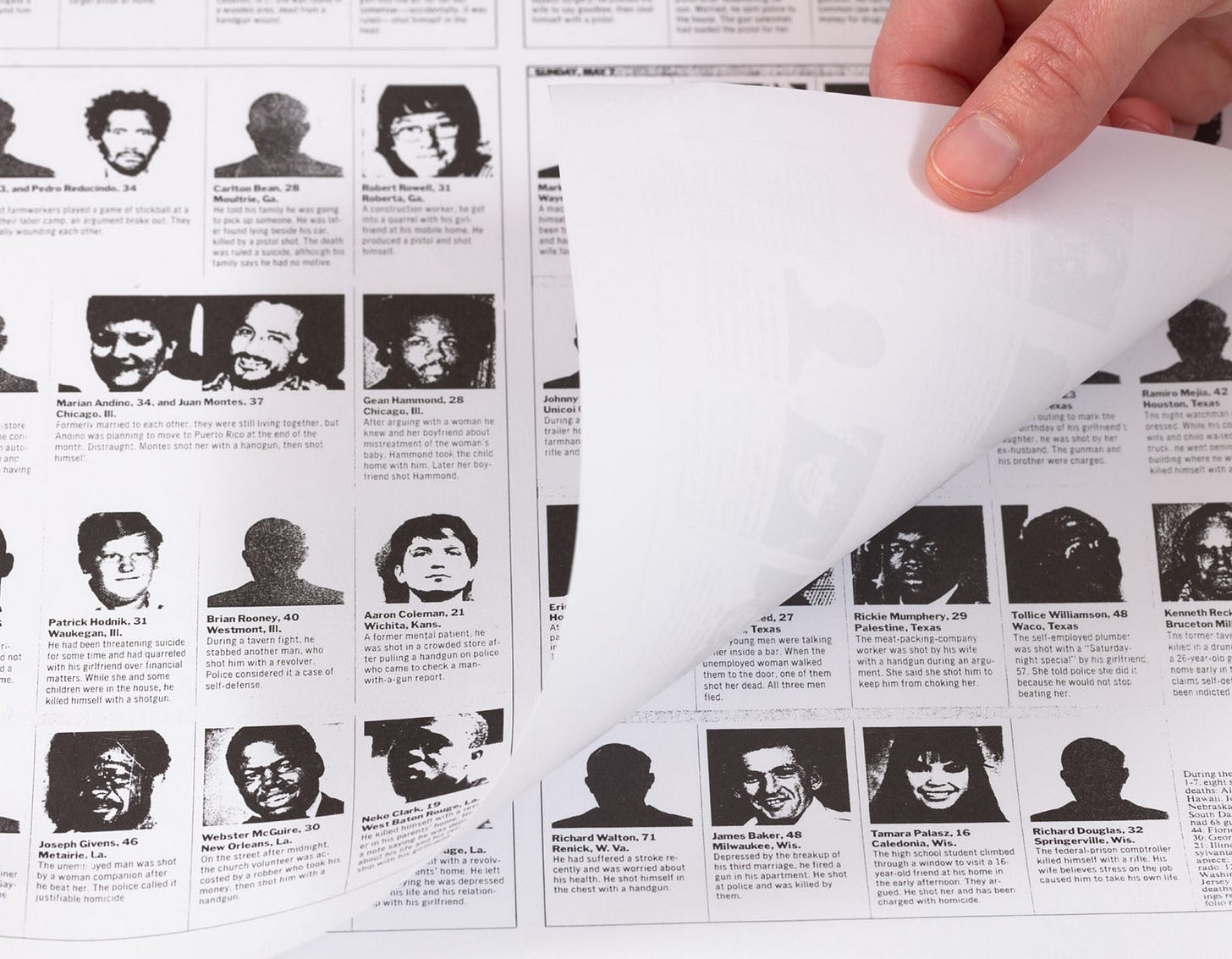

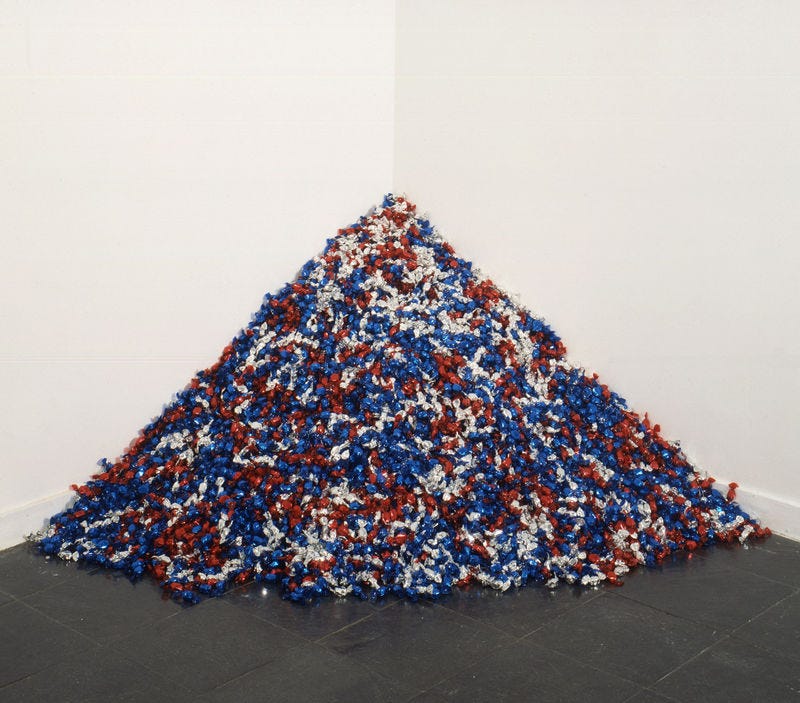

In 1990’s “Untitled” (Death by Gun), González-Torres repurposed newspaper layout strategies to list 460 victims of gun violence in one week of May 1989, transforming stark statistics into a public memorial roll call demanding political reckoning (MoMA PS1; Walker 119). That same year, “Untitled” (USA Today) covered a gallery floor with candies, individually wrapped in red, silver, and blue cellophane (endless supply). Echoing the red, white, and blue palette of the American flag, the piece alludes to USA Today; a mass-market newspaper known for its concise, easily digestible approach to reporting. (Museum of Modern Art; Sandler 58).

The 1991 candy installation “Untitled” (Placebo) spread silver-wrapped sweets across the floor, its title’s double meaning, actual placebo versus noneffect, underscoring medicine’s limits during the AIDS crisis (Burlington Contemporary Journal; Rosenthal 102). In 1992 his city-wide billboard series “Untitled” (It’s Just a Matter of Time) displayed the phrase “Es ist nur eine Frage der Zeit,” its simple text shifting in meaning as light and context changed, provoking reflection on mortality and anticipation (Tate; Mulvey 34).

Later works continued to explore absence and renewal: 1995’s “Untitled” (Golden) strands of beads and hanging device, the sumptuous hue evoking preciousness and ephemerality as viewers consumed the work (Museum of Modern Art; Greenberg 91); 1993’s “Untitled” (Last Light) hung a string of low bulbs whose uneven illumination symbolized vulnerability and the passage of time (Dia Art Foundation; Nochlin 67); and 1992’s “Untitled” (Republican Years) stacked sheets printed with U.S. presidents’ names, each removed page marking institutional erosion (Museum of Modern Art; Butler 148).

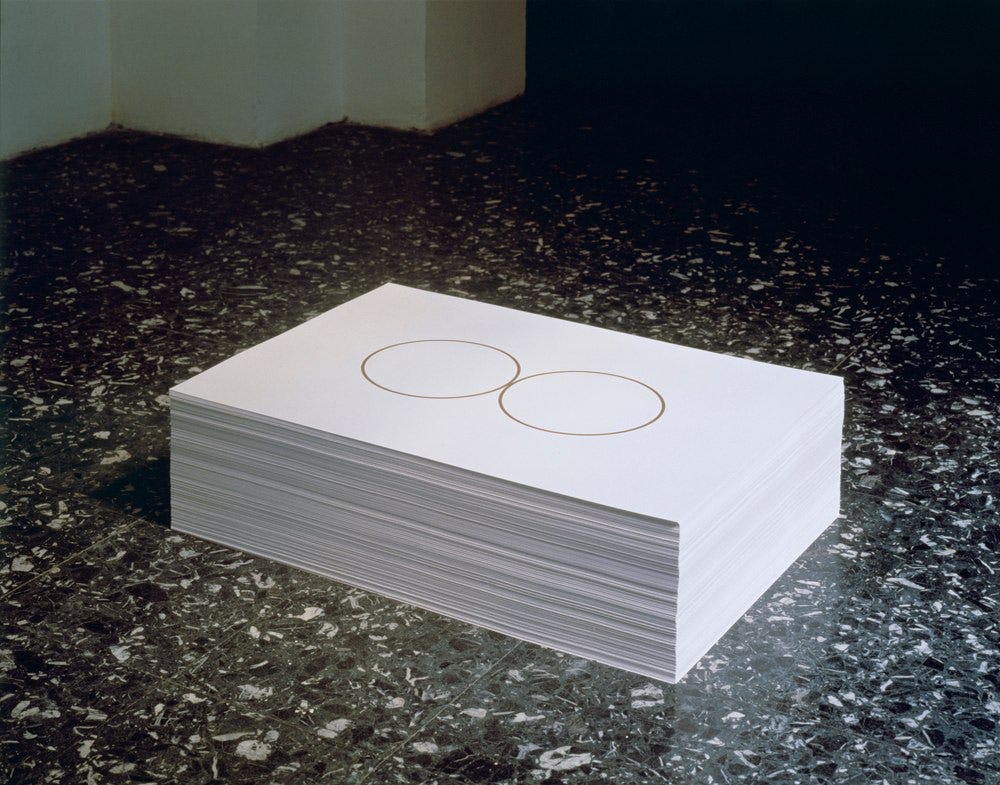

In 1991’s “Untitled” (Double Portrait), two overlapped circles on transparent film formed a layered portrait, exploring identity’s fluid boundaries (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Jones 112), while “Untitled” (For Jeff) (1992) dedicated a work to a friend, personalizing the universal logic of exchange (Dia Art Foundation; Smith 203). Finally, 1995’s “Untitled” (Water) invited viewers to pass through a curtain of beads printed with water-ripple imagery, enacting immersion and the fluid boundary between art and life (Museum of Modern Art; Crimp 81).

Although González-Torres resisted reductive identity labels, arguing that his work transcend categories, his interventions were deeply shaped by his experience as a gay man during the AIDS crisis. By centering absence, empty platforms, depleting candies, desynchronized clocks, he articulated a queer politics of loss that countered mainstream narratives of visibility and triumphalism (Museum of Modern Art; Crimp 65). His participation in Group Material provided both critical framework and public platform for feminist and gay-rights activism, situating his minimal gestures within broader struggles for social justice (Zeller 108).

After his death in Miami on January 9, 1996, the Félix González-Torres Foundation was established to steward his principles of open-ended installation (Dia Art Foundation). His participatory logic influenced relational artists such as Tino Sehgal’s constructed encounters, Rirkrit Tiravanija’s communal meals, and Abraham Cruzvillegas’s autoconstrucción, all of whom share his emphasis on viewer agency and social exchange (Bourriaud 52). Moreover, his fusion of Minimalist form with queer activism presaged debates about affect, memory, and public engagement in contemporary institutional spaces (Rosenthal 120).

Félix González-Torres redefined the boundaries of art, memory, and community through minimalist systems that demand collaboration and care. His “stacks,” candy works, clocks, light strings, and public interventions function as living memorials; each encounter a ritual of remembrance bridging personal grief and collective responsibility. Grounded in queer experience and forged in the urgency of the AIDS crisis, his oeuvre endures as a powerful testament to generosity, loss, and the capacity of art to build community.

References:

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Hill and Wang, 1981.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Les Presses du réel, 1998.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. Routledge, 1993.

Crimp, Douglas. AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism. October, no. 43, 1987, pp. 3–44.

Dia Art Foundation. Félix González-Torres. Dia Art Foundation, diaart.org/exhibition/exhibitions-projects/felix-gonzalez-torres-exhibition/. Accessed 25 Feb. 2025.

Greenberg, Clement. Minimalism. Art and Culture: Critical Essays, Beacon Press, 1961, pp. 90–108.

Judd, Donald. Specific Objects. Arts Yearbook, 1965, pp. 74–82.

Jones, Amelia. Portraiture and Participation. Art Journal, vol. 55, no. 4, 1996, pp. 110–118.

LeWitt, Sol. Paragraphs on Conceptual Art. Artforum, vol. 5, no. 10, 1967, pp. 79–83.

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.). The Art Institute of Chicago, www.artic.edu/artworks/152961/untitled-portrait-of-ross-in-l-a. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

Untitled’ (Death by Gun). MoMA PS1, www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/4971. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

“Untitled’ (Golden). The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/collection/works/81073. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

Untitled (It’s Just a Matter of Time). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/felix-gonzalez-torres-11937. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

Museum of Modern Art. Félix González-Torres. MoMA, www.moma.org/artists/2233-felix-gonzalez-torres. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

Museum of Modern Art. Félix González-Torres: Catalogue Raisonné. MoMA Publications, 2000.

Mulvey, Laura. Time and the Gaze: Reflections on the Half-Life of Beauty. MIT Press, 2006.

Nochlin, Linda. The Polity and the Personal: Light and Life. Art in America, vol. 82, no. 5, May 1994, pp. 66–75.

Rosenthal, Mark. Candy and Crisis: Félix González-Torres’s Clinical Interventions. Art Journal, vol. 60, no. 2, 2001, pp. 100–125.

Sandler, Irving. Media and Memory in the Work of González-Torres. Art Issues, vol. 17, no. 3, 1992, pp. 55–60.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Félix González-Torres. SFMOMA, www.sfmoma.org/artist/Felix_Gonzalez-Torres/. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

Smith, Terry. Friendship and Loss: Contemporary Queer Memorials. October, no. 85, 1998, pp. 200–215.

Walker, John A. Violence and Visibility: Public Memorials in Contemporary Art. Art Journal, vol. 53, no. 2, 1994, pp. 115–122.

Zeller, Arlene. Group Material: Art and Activism in New York. Aperture, no. 138, 1995, pp. 100–110.

This was great. Thank you for your thoughts and for creating the visual movement of my Pride this year. I look forward to each post with the childlike joy in Christmas morning.