Berthe Morisot occupies a singular place in art history as one of the founding figures of Impressionism and one of its few prominent female practitioners. Her work, characterized by a luminous palette, sensitive brushwork, and an intimate portrayal of domestic and outdoor life, not only redefined modern painting but also challenged the rigid gender conventions of nineteenth‑century France.

Berthe Morisot was born on January 14, 1841, in Bourges, France, into a prosperous bourgeois family. Her father, Edmé Tiburce Morisot, was a senior local administrator, and her mother, Marie‑Joséphine‑Cornélie Thomas, was related to the celebrated Rococo painter Jean‑Honoré Fragonard (Encyclopædia Britannica). The family’s relocation to Paris in 1852 placed Morisot at the center of France’s vibrant cultural life, where she was afforded private lessons in drawing and painting; a rare opportunity for a young woman of her time.

Under the tutelage of artists such as Geoffroy‑Alphonse Chocarne and later Joseph Guichard, Morisot developed the technical skills typical of the academic tradition through careful copying of Old Master paintings at the Louvre (National Museum of Women in the Arts). A decisive influence came when she encountered Jean‑Baptiste Camille Corot; his emphasis on natural light and outdoor painting (plein air) profoundly affected her approach, setting the stage for her later innovations. Despite formal restrictions, women would not be admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts until 1897, Morisot’s determination and access to private instruction allowed her to blend academic rigor with a fresh, modern vision (Higonnet 27; Oxford Art Online).

Morisot’s professional career began with her debut at the Salon de Paris in 1864, where two of her landscape paintings were accepted. This early success marked her as an exceptional talent, especially given the obstacles women faced in the art world. Over the next decade, she exhibited regularly at the Salon, gradually establishing her reputation.

A watershed moment occurred in 1874 when Morisot participated in the first independent Impressionist exhibition; a seminal event that signaled a collective break from academic constraints (Rewald 112). As the only woman in the group, her inclusion not only challenged prevailing gender norms but also helped to broaden the movement’s aesthetic scope. Morisot’s work, emphasizing immediacy, light, and everyday subject matter, captured a modern vision that resonated with audiences and fellow artists

Her long-standing relationship with Édouard Manet was particularly influential. After meeting him at the Louvre in 1868, their creative dialogue, though sometimes marked by condescension, as noted in Sebastian Smee’s recent study, helped shape her evolving style. Manet’s advice, though unsolicited, pushed Morisot to refine her technique and assert her artistic identity. Their correspondence and shared circle (including figures such as Edgar Degas and Claude Monet) highlight a mutual influence that enriched both their works (Smee 2024).

Art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel also played a key role in promoting Morisot internationally, purchasing many of her paintings and thereby ensuring that her work reached a broader audience. His innovative marketing strategies were critical to the Impressionists’ eventual commercial success (Rewald).

Morisot’s paintings are celebrated for their innovative approach to light, color, and composition. Her oeuvre spans a wide range of subjects, from expansive urban landscapes to intimate domestic scenes, and is unified by a distinctive aesthetic that emphasizes both immediacy and delicacy.

Central to Morisot’s technique is her adept use of plein-air painting. Works such as View of Paris from the Trocadero (1871–72) demonstrate her ability to capture the ephemeral quality of natural light. By employing loose brushstrokes and a bright, airy palette, she conveys not only a visual record of Paris in the aftermath of the Franco‑Prussian War but also an atmosphere of transience and renewal (Rewald; The Art Story).

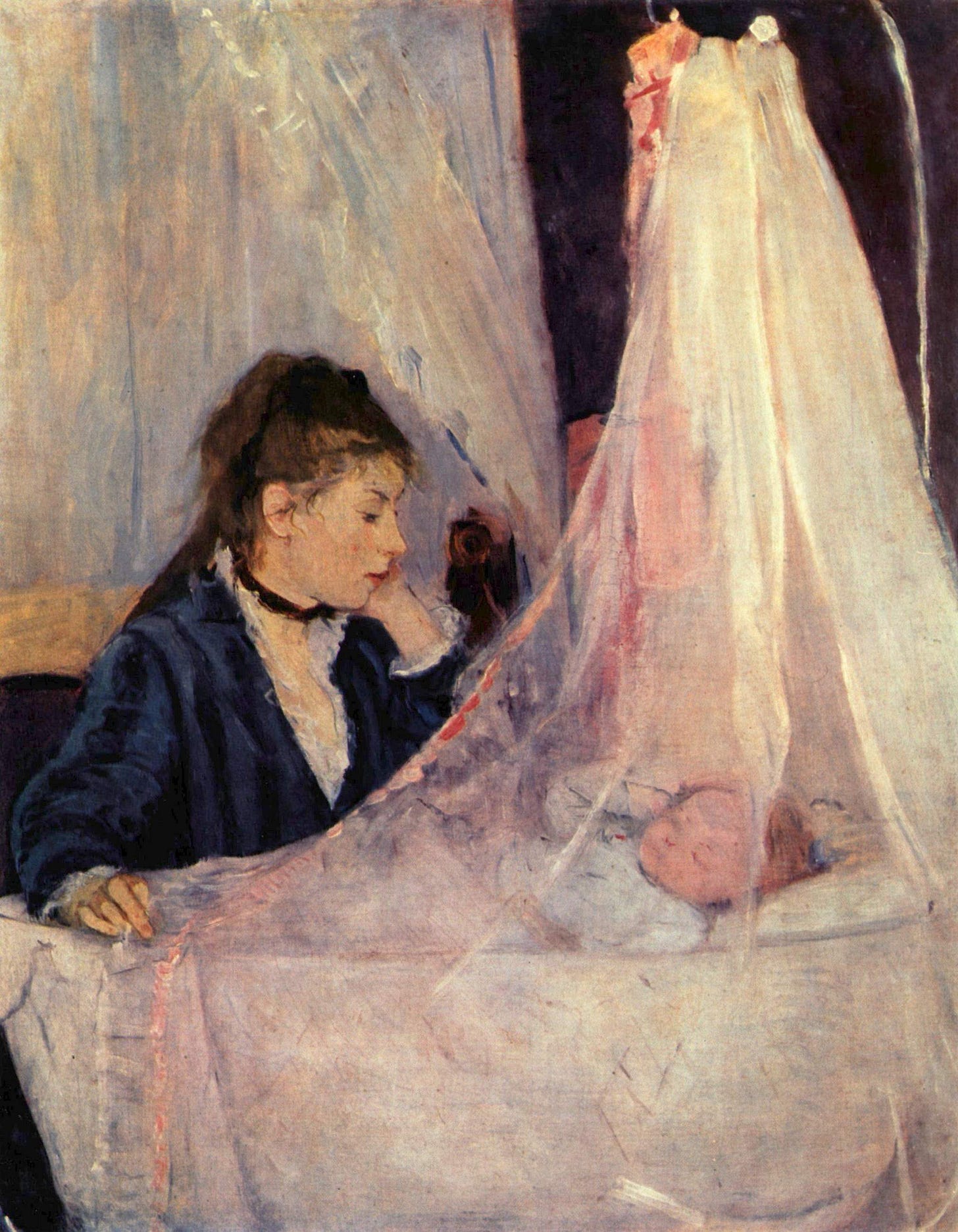

Morisot’s focus on domestic subjects,.such as in The Cradle (1872), is equally groundbreaking. In this painting, she portrays her sister Edma watching over her sleeping daughter with a compositional balance that creates a sense of intimate harmony. The delicate interlocking of shapes and the subtle treatment of light and shadow imbue the work with emotional depth. Critics have long admired this tender portrayal of motherhood, which has come to be seen as a radical assertion of female subjectivity (Higonnet; Nochlin).

A defining feature of Morisot’s art is her innovative use of color. Her palette is dominated by light tones (whites, pastels, and delicate hues) that create a luminous quality across her canvases. Her brushwork, characterized by a loose yet deliberate application of paint, sometimes leaves textures that invite close examination. This approach challenged traditional notions of finish and precision in academic painting and contributed to the dynamic, modern quality of her work (Chadwick; Oxford Art Online).

Morisot’s career unfolded in a society steeped in patriarchal norms, where women artists were often relegated to a secondary status. Contemporary critics sometimes dismissed her work as merely “feminine” or “delicate,” failing to acknowledge the technical innovation and emotional complexity of her paintings (Nochlin 1971). Nevertheless, her talent was recognized by her peers, and she developed strong personal and professional networks within the Impressionist circle.

Her decision to sign her work with her maiden name was a deliberate assertion of her artistic identity; one that separated her achievements from her domestic roles as wife and mother. Although her subject matter was often confined to the domestic sphere by social convention, feminist art historians such as Linda Nochlin and Griselda Pollock have argued that this focus was itself a radical choice that challenged traditional expectations. By portraying intimate, everyday moments with profound sensitivity, Morisot redefined what it meant to create “great” art (Pollock; Nochlin).

Institutional retrospectives at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Musée d’Orsay, and major international exhibitions have contributed to a reappraisal of her work. Her paintings now command increased recognition in both scholarly literature and the art market, underscoring her importance as a central figure in the evolution of modern art (Higonnet; Smee).

Berthe Morisot’s legacy is multifaceted. As a pioneering female artist in the male-dominated world of Impressionism, she expanded the aesthetic vocabulary of modern art through her innovative use of light, color, and composition. Her sensitive portrayals of both urban and domestic life continue to resonate with audiences, and her career challenges the traditional narratives of art history by demonstrating that the intimate and the everyday can be as revolutionary as grand historical themes. Morisot’s enduring influence is reflected in the continued scholarly and market reappraisal of her work, ensuring that her contributions to the evolution of Impressionism and modern art are finally recognized in their full complexity.

References:.

Encyclopædia Britannica. Berthe Morisot. Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Berthe-Morisot. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Higonnet, Anne. Berthe Morisot: A Life in Art. University of California Press, 1995.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. Thames & Hudson, 2012.

John Rewald. Impressionism: A History of French Art. Harper & Row, 1973.

Linda Nochlin. Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? Art News 69 (Jan. 1971): 22–39.

Griselda Pollock. Old Mistresses: Women, Art, and Ideology. Pantheon, 1981.

Oxford Art Online. Berthe Morisot. Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, https://oxfordartonline.com/groveart. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

National Museum of Women in the Arts. Berthe Morisot. NMWA, https://nmwa.org/art/artists/berthe-morisot. Accessed 15 Jan. 2025.

Smee, Sebastian. Paris in Ruins: Love, War and the Birth of Impressionism. Scribner, 2024.

She is always a favorite when I want to pick up my brush again. It’s like a soft step into a blank canvas. You watch her paint it as you view her work. It unfolds before us like a story of the work about the process of working it. And yet! In completeness it presents a truth in a moment. So while from a technical point I always see her process she reminds me to be in the moment. No matter how long it takes to make that moment real on the canvas, the breath of life is but a second she portrays, authentically pure, every single time.

RAH-Thank you for this piece. Enjoyed learning about this artist!