David Michael Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) stands as an emblematic figure of late twentieth-century American art, whose multidisciplinary practice fused autobiography, queer identity, and fervent political activism. Born in Red Bank, New Jersey, and rising to prominence in New York City’s East Village during the turbulent 1980s, Wojnarowicz made indelible contributions across painting, photography, film, performance, sound, and prose. His art not only documented his own experiences as a young, homeless queer man navigating addiction and street life, but also served as a searing indictment of societal neglect in the face of the AIDS crisis. As critic Holland Cotter has observed, Wojnarowicz’s work “is at once deeply personal and broadly political,” compelling audiences to confront the human cost of bigotry, stigma, and governmental inaction (Cotter).

David Wojnarowicz’s early life was indelibly shaped by familial rupture, abuse, and the precariousness of street existence. Born on September 14, 1954, to Dolores McGuinness and Ed Wojnarowicz, he and his two siblings suffered physical abuse at the hands of their father after their parents’ bitter divorce (“David Wojnarowicz”). Kidnapped by their father and moved between Michigan and Long Island, the siblings endured violent discipline until they escaped and, through a New York City phone book, located their Australian-born mother in the early 1960s (“David Wojnarowicz”). Settling in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Wojnarowicz graduated from the High School of Music & Art; a rare point of stability in what he later termed a “life of escape and rejection” (“David Wojnarowicz”). Yet by age seventeen, he was living fully on the streets, sleeping in halfway houses and squats, and sustaining himself through sex work in Times Square’s burgeoning hub of illicit exchange (“David Wojnarowicz”; “How One Artist Forever Changed the AIDS Crisis”). These years of urban precarity, where survival necessitated both hypervisibility and masked anonymity, forged the template for his enduring interest in the fraught interplay between queer desire, bodily vulnerability, and the punitive gaze of society.

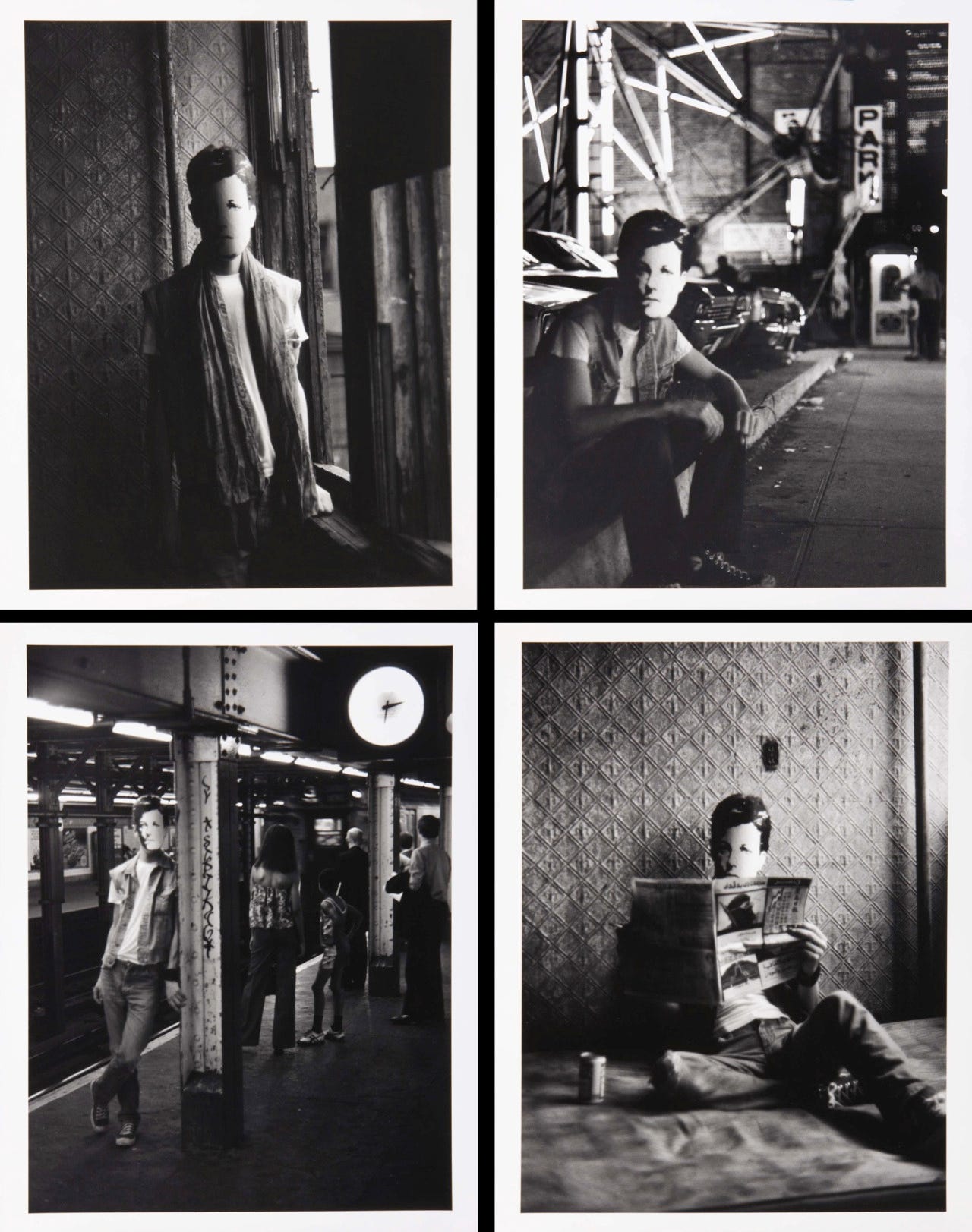

In his celebrated memoir Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, Wojnarowicz recounts escaping an abusive foster home and adopting the pseudonym “Arthur Rimbaud” as a means of self-fashioning: “I became Rimbaud,” he writes, “because he was a poet, because he was a queer, because he was a runaway [… and] because he died young” (Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives). This invocation of Rimbaud, the nineteenth-century French poet whose early work is steeped in both homoeroticism and iconoclastic rebellion, exemplifies Wojnarowicz’s conviction that queer artists must refuse respectability and embrace radical self-mythologizing. Scholar Mysoon Rizk elaborates that Arthur Rimbaud in New York, one of Wojnarowicz’s earliest major bodies of work, “transposes Rimbaud’s story onto late-1970s Manhattan, aligning the poet’s legacy of exile with the artist’s own experiences of homelessness, sex work, and creative insurgency” (“Arthur Rimbaud in New York”). In these gelatin-silver prints, Wojnarowicz staged himself, masked as Rimbaud, amid the decaying piers and abandoned lots where he once slept, effectively mapping queer lineage onto the derelict spaces of the East Village.

The introverted intensity of Wojnarowicz’s personality found a crucial outlet in his relationship with photographer Peter Hujar (1934–1987). Introduced in 1981 through mutual friends in the downtown scene, Hujar recognized Wojnarowicz’s potential, urging him to master the technical rigor of darkroom work (“David Wojnarowicz”). Their bond, at once romantic and artistic, thrust Wojnarowicz into the orbit of New York’s burgeoning photo-art community. Following Hujar’s death from AIDS on November 26, 1987, Wojnarowicz inherited his mentor’s darkroom and loft near Second Avenue, converting those spaces into the locus for some of his most incendiary works (“David Wojnarowicz”; “Peter Hujar: Speed of Life”). Hujar’s death reverberated through Wojnarowicz’s life; diagnosed with HIV in late 1988 (“David Wojnarowicz”), he transformed personal grief into a clarion call, channeling sorrow into furious, elegiac art that would indict societal and governmental apathy toward the AIDS epidemic.

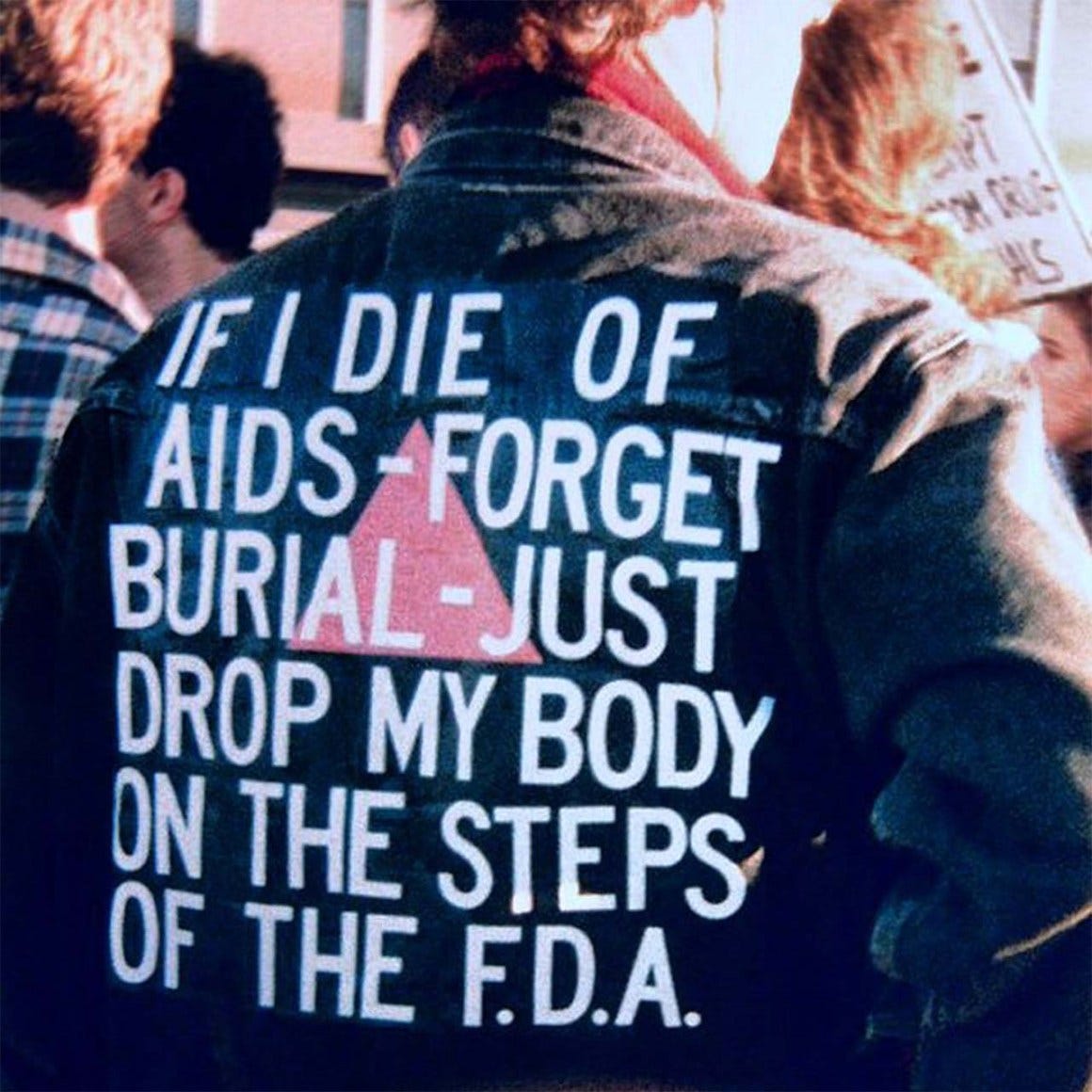

Throughout his formative years, Wojnarowicz resisted reductive narratives of victimhood or isolated suffering. Instead, as scholar James McGrath asserts, “Wojnarowicz’s queer identity was generative, a site of both revelation and resistance, refusing to be severed from broader questions of race, class, and institutional power” (McGrath 45). His tape journals, later transcribed in Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz, reveal a mind perpetually probing the intersections of personal trauma and collective injustice: “If I die of AIDS, forget burial, just drop my body on the steps of the F.D.A.” (Wojnarowicz, Weight of the Earth). By situating his own mortality as an act of protest, he insisted that queer life and death be public spectacles that force society to confront its own dehumanization of vulnerable populations.

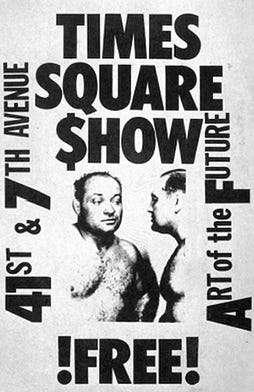

By the late 1970s, Manhattan’s East Village had become a crucible for experimental art, music, and performance, incubating a DIY ethos that embraced graffiti, collage, and provocative public interventions (“Arthur Rimbaud in New York”). Wojnarowicz, newly returned from periods of instability outside New York, quickly embedded himself within the loose-knit networks of Collaborative Projects (Colab) and ABC No Rio; artist-run collectives that championed cultural activism in response to the social and economic upheavals of the Reagan era (“David Wojnarowicz”; Heaton, “The Times Square Show”). Colab, formed in 1977, provided a model for decentralized, artist-driven projects, culminating in The Times Square Show (1980), an open-access exhibition that transformed a derelict massage parlor into a thirty-day cultural happening (Heaton). Wojnarowicz contributed street drawings and graffiti-like text to this milieu, collaborating with fellow insurgent artists, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Kiki Smith, who shared an interest in eroding the boundaries between “high art” and street culture (“David Wojnarowicz”; “Screaming in the Street”).

ABC No Rio, squatted at 156 Rivington Street in 1980, became another vital site for Wojnarowicz’s early experimentation (“ABC No Rio”; Franklin). Hosting radical exhibitions, punk rock matinees, zine-based workshops, and free jazz performances, No Rio cultivated an anti-capitalist ethos that resonated with Wojnarowicz’s own antagonism toward mainstream institutions (“ABC No Rio”). He both attended and exhibited at No Rio; his street drawings and early mixed-media works reflecting the raw energy of a community committed to cultural dissent (“David Wojnarowicz”). This period honed his collaborative instincts, forging friendships with musicians, performance artists, and fellow visual creators whose cross-disciplinary activities would inform his later embrace of film, sound, and performance art.

The participatory character of these early experiences is evident in Wojnarowicz’s later insistence that art be immersive and communal. As scholar Fiona Anderson observes, “The East Village scene was not about individual genius; it was about collective insurgency,” a principle that Wojnarowicz extended into his own collective actions; poster campaigns for ACT UP, street interventions condemning Reagan-era homophobia, and videotaped manifestos that solicited public outrage (Anderson and Tobin). In this crucible of creative anarchy, Wojnarowicz solidified a conviction that art must disrupt and demand, forging a path from guerrilla street art to institutional critique.

Wojnarowicz’s oeuvre defies categorization, spanning photography, collage, painting, film, performance, sound, and prose. His formal approach was consistently shaped by an urgency to bear witness; to document the precariousness of queer existence, the ravages of AIDS, and the hypocrisies of political power.

One of Wojnarowicz’s earliest major projects, Arthur Rimbaud in New York consists of twenty-four black-and-white gelatin-silver prints in which the artist dons a papier-mâché mask of Rimbaud and stages dramatic tableaux across the Lower East Side (“Arthur Rimbaud in New York”). In these images, the masked figure lies naked on a dilapidated mattress against graffiti-smeared walls, peers through subway grates, or stares out from a graffiti-covered car, embodying both the Romantic myth of the exiled poet and the gritty reality of late-1970s Manhattan. By assuming Rimbaud’s identity, Wojnarowicz aligned his own experiences of homelessness, sex work, and queer marginalization with those of a historical queer forebear, effectively constructing a lineage of resistance that transcended time and geography. As Mysoon Rizk has argued, “Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud is not a passive homage but a reclamation; an insistence that queer histories be recontextualized within the physical landscapes of a hostile present” (Rizk). These early photographs reveal the nascent features of his later practice: a fascination with masquerade, the power of the gaze, and an unflinching desire to collapse the distance between self and myth.

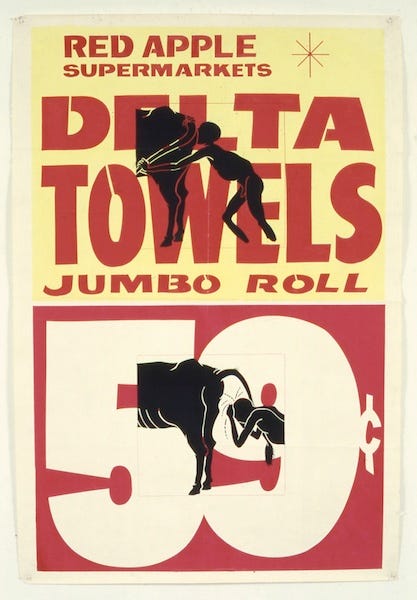

In Delta Towels (1983), David Wojnarowicz employed commercial screenprinting and spray paint on a found object, specifically, a mass-produced advertising poster, for a singular mixed-media work, not a series. While not a photomontage or collage in the traditional sense, the piece reflects Wojnarowicz’s engagement with vernacular imagery, subcultural symbols, and the visual language of mass-market consumerism. The title, Delta Towels, refers to a brand rather than the Mississippi Delta, and there is no direct indication that the work engages with blues music or the region's racial history. Instead, its haunting quality emerges through the artist’s transformation of commercial detritus into a cryptically altered surface. As art historian Jonathan Fineberg observes more broadly of Wojnarowicz’s method, the artist “recasts vernacular imagery through a haunting lens, tracing how memory, violence, and desire overlap in concealed, overlapping strata” (Fineberg 120). Delta Towels resists easy legibility through its degraded imagery and destabilized iconography, emblematic of Wojnarowicz’s larger practice of embedding psychic, social, and political trauma within the visual field.

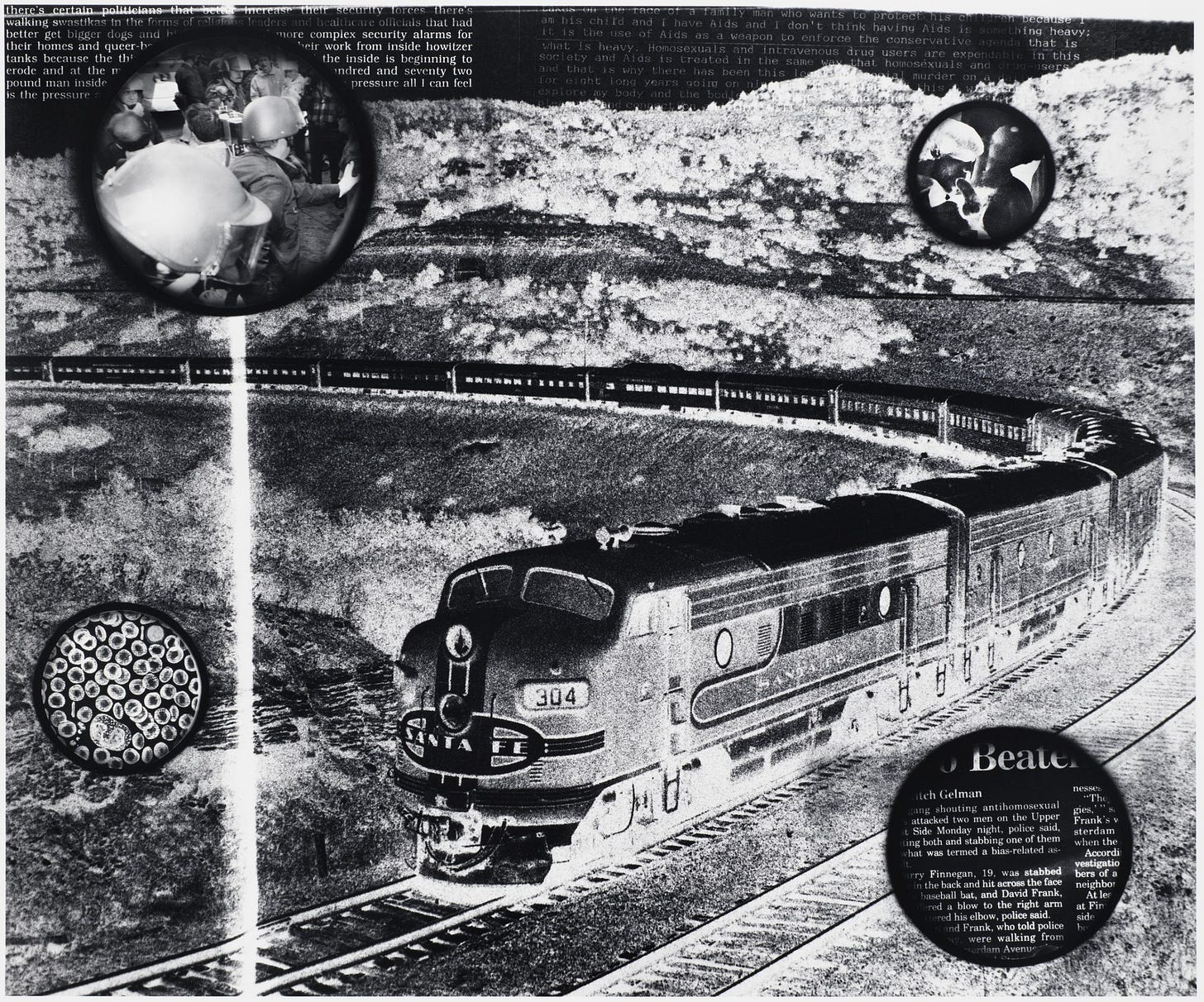

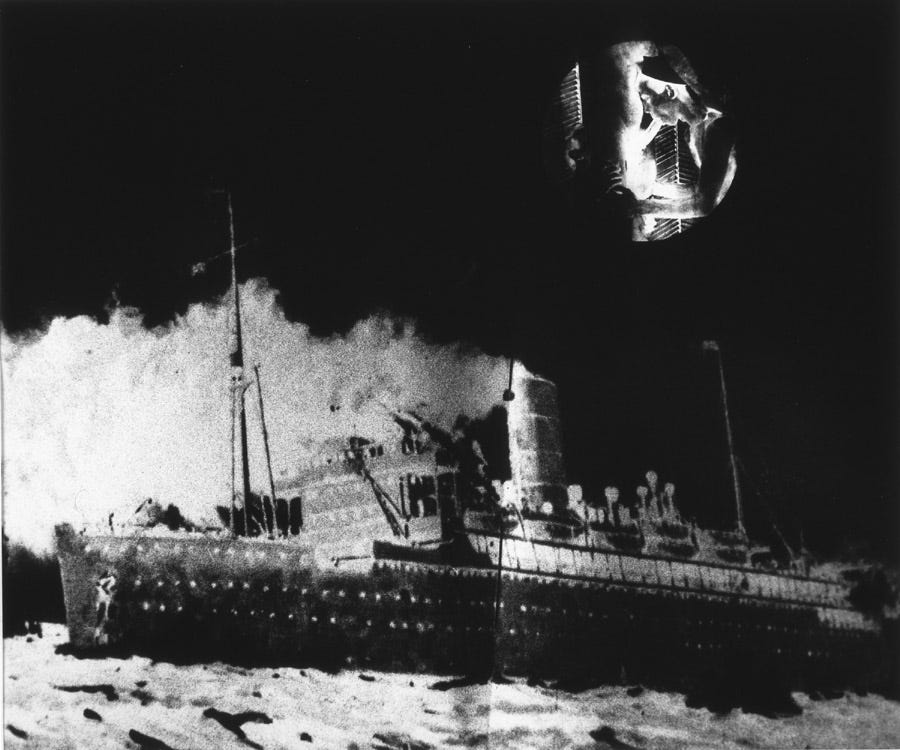

Executed between approximately 1987 and Wojnarowicz’s death in 1992, the “Sex Series” comprises gelatin-silver prints depicting anonymous gay men, often street hustlers, in explicit sexual acts (Conrad 23). Working mostly in Peter Hujar’s darkroom, Wojnarowicz printed these raw street photographs at high contrast, then overlaid them with acrylic paint, collaged pornographic fragments, and appropriated text drawn from tabloids and government reports (Conrad 24). Anna-Maria Conrad contends that the “Sex Series” “articulates the disjunction between the body as an erotic object and the body ravaged by illness and social neglect, forcing viewers to reckon with desire as both a site of pleasure and existential threat” (Conrad 27). By refusing to sanitize or render these bodies invisible, Wojnarowicz transformed the erotic into a potent arena of resistance; asserting that queer presence itself was a defiance of both public morality and institutional indifference.

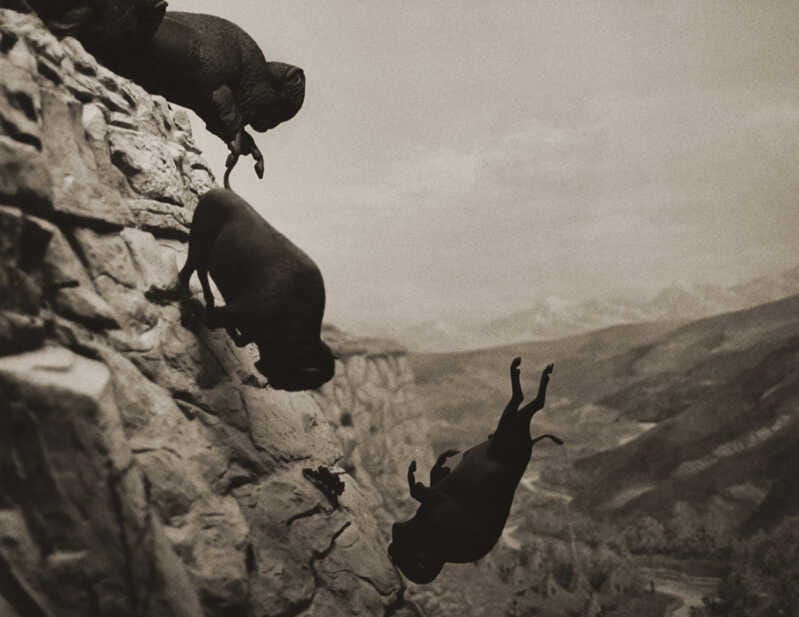

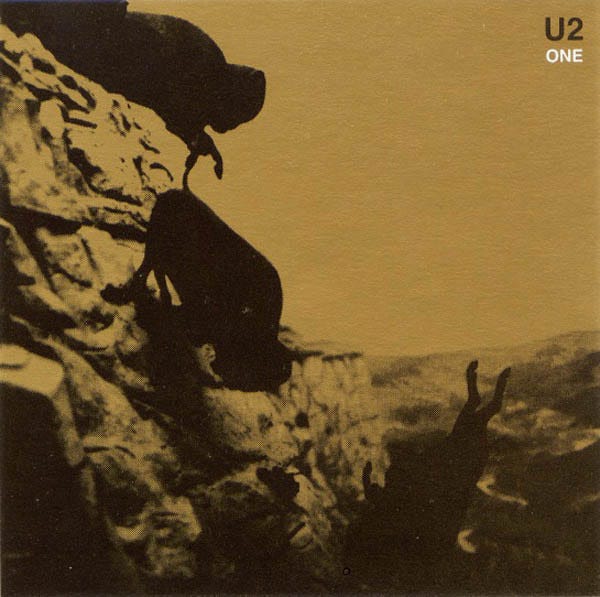

One of Wojnarowicz’s most iconic standalone images, Untitled (Buffaloes) (1988) features a herd of buffalo stampeding across a desolate landscape under a deep, moonlit sky (Untitled (Buffaloes)). On its surface, the photograph is a striking wildlife composition; beneath, it functions as an allegory for collective resilience in the face of extinction. The buffalo, once a symbol of Native American sovereignty decimated by colonial violence, here evoke queer communities navigating the lethal wilderness of the AIDS crisis. In 1991, rock band U2 widely disseminated Buffaloes as the cover for their single “One,” funneling proceeds to AIDS charities and effectively turning the image into a transnational emblem of solidarity (Untitled (Buffaloes)). The choice to deploy a wilderness scene, bereft of human presence, heightens the sense of abandonment, as if these great beasts charge onward despite being orphaned by a world that no longer values their existence. In this sense, Buffaloes encapsulates Wojnarowicz’s prescient grasp of the language of metaphor: the photograph’s meditative quietude belies a furious insistence on communal survival.

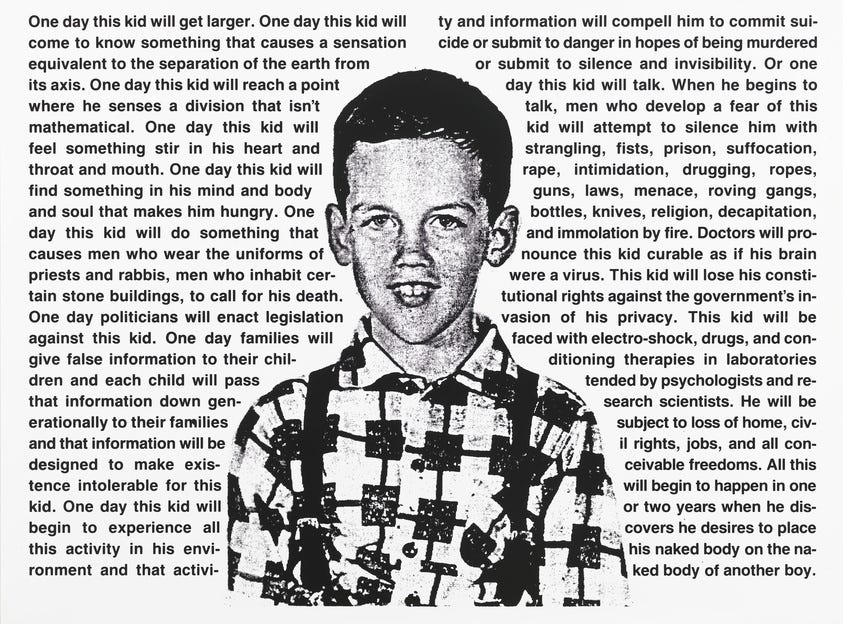

Executed in 1990, Untitled (One Day This Kid….) is a black-and-white photostat featuring a childhood photograph of David Wojnarowicz himself, centered on a plain white background, surrounded by blocks of typed text. Contrary to some interpretations, the work does not employ a deep red background or neon palette; its visual starkness lies in the contrast between the monochrome image and the blunt, unadorned typography. The text, beginning with the line “One day this kid will get larger”, lists the various forms of violence, marginalization, and hatred the child (and, by extension, queer youth) will face in society. Wojnarowicz’s choice to use his own childhood image underscores the personal stakes of systemic homophobia and the deep-rooted nature of social prejudice. The child figure becomes both vulnerable and emblematic, a stand-in for all queer youth subject to societal rejection. As critic Tammy Oler observes, the piece’s power derives from “the cumulative force of its accusations; relentless, deeply personal, and impossible to ignore” (Oler). By directly linking queer identity to early developmental stages, Wojnarowicz confronts viewers with the reality that discrimination begins long before adulthood and implicates all social institutions, from family to education to the state.

Perhaps no single work captures Wojnarowicz’s fusion of visceral imagery and political indictment more powerfully than A Fire in My Belly (two versions: 1986 and 1987). Originally shot on Super 8 film and later transferred to digital video, the twenty-one-minute montage intersperses found footage, ants crawling over a plastic crucifix, close-ups of decaying animal carcasses, images of Latino prisoners behind bars, with archival devotional imagery and rapid-fire shots of Wojnarowicz himself slapping his face before a ringing telephone (Tyburczy 15). The soundtrack, drawn from Diamanda Galás’s Plague Mass, reverberates with wailing vocals that conjure both lamentation and fury. As art historian Jennifer Tyburczy observes, “In conflating religious iconography with images of decay, Wojnarowicz indicts institutional religion’s failure to protect and minister to queer bodies dying of AIDS” (Tyburczy 16). The work’s public infamy, when, in December 2010, an eleven-second clip of ants crawling over a crucifix prompted congressional outcry and the Smithsonian’s removal of the film from Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, underscores its enduring capacity to provoke debate over censorship, sacrality, and queer visibility (Nicoll). In systematically unsettling viewers’ expectations, juxtaposing the sacred and the grotesque, the living and the decaying, A Fire in My Belly forces a reckoning with the social costs of ignorance and indifference.

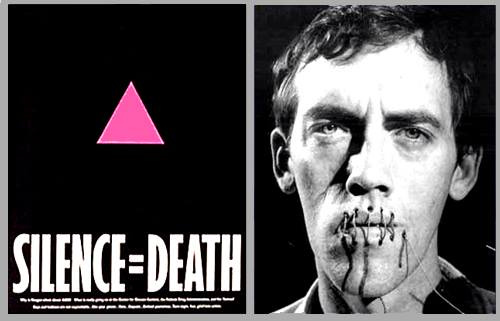

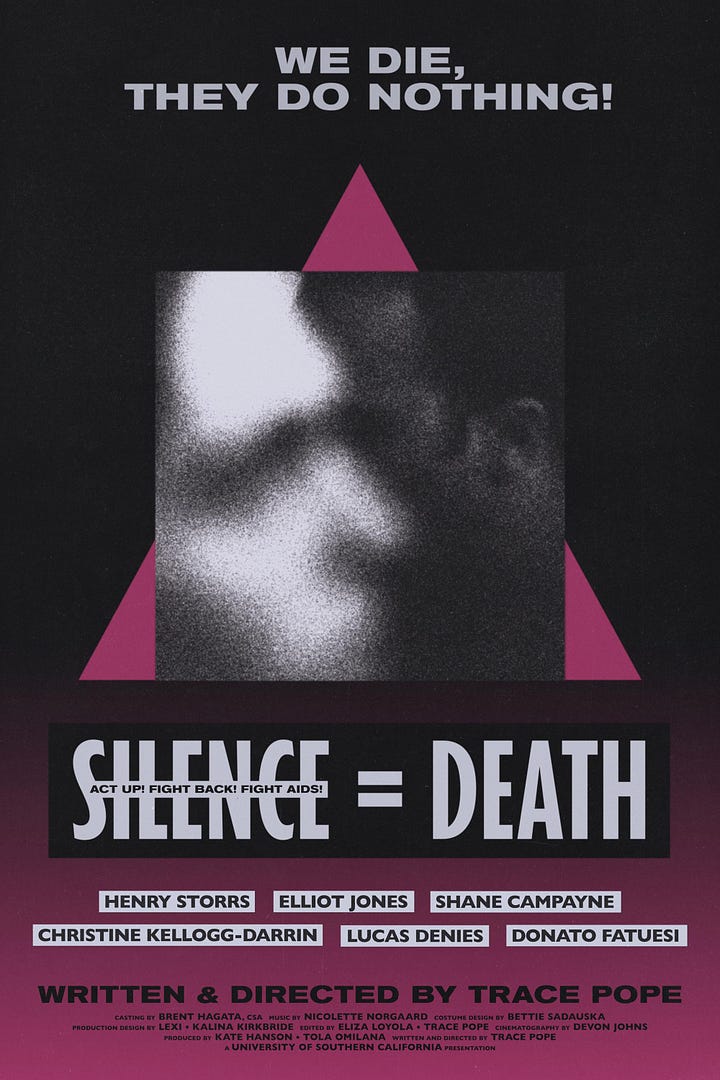

Following his HIV diagnosis in late 1988 (“David Wojnarowicz”), Wojnarowicz emerged as one of the most uncompromising voices within New York City’s AIDS activism milieu. Rejecting the notion that artists remain “above the fray,” he joined ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and contributed aggressively to the group’s aesthetic strategies, designing posters that paired incisive slogans, “When People Do Care, People Become Loud”, with stark imagery drawn from his own queer-inflected visual lexicon (Screaming in the Street). In 1989, he appeared in Rosa von Praunheim’s documentary Silence = Death, demarcating a generation’s refusal to endure governmental inaction (“Silence = Death”). His collaborative short film Listen to This (1992), co-directed with video artist Tom Rubnitz, combined documentary footage of street protests with found footage of institutional violence, forging a media collage that insisted on public accountability (Rubnitz). In these works, Wojnarowicz deployed his own body as a canvas of visibility: whether recording his HIV-positive status or presenting his specter in public performances, he transformed personal vulnerability into collective fury.

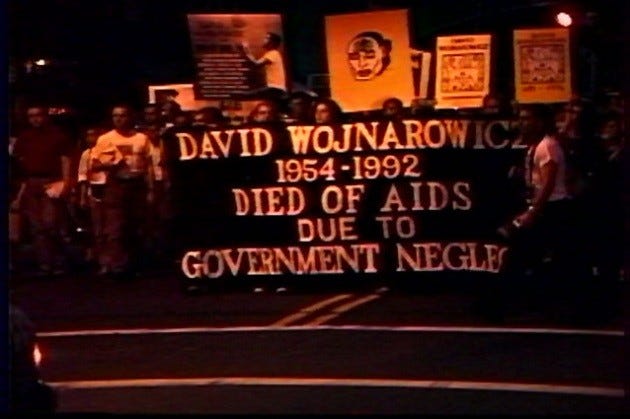

Perhaps the most galvanizing manifestation of Wojnarowicz’s political will was his insistence on a “political funeral” in July 1992. As Weight of the Earth recounts, Wojnarowicz had specified in his taped instructions that his ashes be scattered on the steps of a government building; an act of protest against Reagan-era and Bush–H.W. Bush neglect of the AIDS crisis (Wojnarowicz, Weight of the Earth). After his death on July 22, 1992, at age thirty-seven, his friends and ACT UP comrades staged a march through the East Village on July 29 carrying a banner proclaiming, “DAVID WOJNAROWICZ, 1954–1992, DIED OF AIDS DUE TO GOVERNMENT NEGLECT” (Wojnarowicz Foundation). This “political funeral” dramatized his conviction that queer death must be inscribed onto the public consciousness, not quietly interred. In 1996, his partner Tom Rauffenbart, honoring Wojnarowicz’s instructions, took some of his ashes to the White House lawn, echoing the theatricality of protest pioneered by the AIDS activist David Robinson in 1992 (“David Wojnarowicz”).

Wojnarowicz’s art thus became inseparable from his activism: his photographic series, films, and writings served as weapons in the broader struggle against censorship and governmental apathy. The 2010 Hide/Seek controversy exemplifies this convergence. When Eric Cantor and other conservative leaders pressured the Smithsonian to censor A Fire in My Belly, activists staged protests outside the National Portrait Gallery, carrying copies of Wojnarowicz’s manifesto and demanding “Don’t Give Me a Memorial If I Die. Give Me a Demonstration” (Smithsonian Institution). The debate illuminated the persistent tension between queer art that confronts orthodoxy and institutional impulses toward appeasement. As Jennifer Tyburczy remarks, “The censorship of Wojnarowicz’s work in 2010 was not merely a battle over ants on a crucifix; it was a symptom of larger anxieties regarding queer publics and the power of art to incite political change” (Tyburczy 18).

Although Wojnarowicz succumbed to AIDS-related complications on July 22, 1992 (Wojnarowicz Foundation), his artistic and activist imprint continued to reverberate throughout the 1990s and into the present. In 1996, his ashes scattered on the White House lawn by ACT UP centered his memory within a tradition of radical queer protest (“David Wojnarowicz”). That same year, multiple institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and Fales Library at New York University, began acquiring his archives, ensuring that researchers could access his notebooks, darkroom prints, videotapes, and correspondence (“David Wojnarowicz”; Franklin). The Fales Library’s David Wojnarowicz Papers, which include early zines, street drawings, and unpublished poems, have become a crucial repository for understanding the complexities of downtown queer culture in the 1980s (Wojnarowicz Foundation; “David Wojnarowicz”).

Major retrospectives have reaffirmed Wojnarowicz’s enduring relevance. In 2018, the Whitney Museum of American Art presented David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night, the institution’s first comprehensive survey of his work (“David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night”). Curators David Kiehl and David Breslin organized the exhibition thematically; tracing his early street drawings and collaborations, his photographic and mixed-media series, his activist film work, and his written testimonies, thereby illuminating the consistent thread of resistance that ran through his practice (“David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night”). Including never-before-exhibited pieces such as early graffiti drawings from ABC No Rio and experimental sound works, the retrospective underscored Wojnarowicz’s status as a “cultural sculptor,” forging narratives of queer grief and rage into porous, multimedia forms (Heaton).

Academic and popular discourse has continued to excavate aspects of Wojnarowicz’s impact. The 2022 documentary Wojnarowicz: Fck You Fggot Fcker, directed by Chris McKim, features interviews with friends, collaborators, and critics, underscoring parallels between the political repression of the 1980s and contemporary struggles under the Trump administration (“Wojnarowicz: Fck You Fggot Fcker”). Critics note that Wojnarowicz’s legacy is not confined to historical memory but functions as a blueprint for present-day activist art: his conflation of intimate testimony with collective upheaval prefigures social media; driven campaigns and viral visual interventions that demand accountability for systemic injustices. As Kyle Croft, executive director of Visual AIDS, has written, “Wojnarowicz’s insistence on merging vulnerability with fury continues to guide queer generations facing new battles over bodily autonomy and state-sponsored violence” (Croft).

Commemorative events, such as the NYC AIDS Memorial’s 70th birthday celebration (September 14, 2024), which included readings, performances, and the dedication of a park bench, attest to Wojnarowicz’s ongoing cultural resonance (“Commemorative Events”). The unveiling of AIDS Memorial Quilt panels bearing his name in 2022 further situates him within a collective ritual of mourning and remembrance (Wojnarowicz Foundation). In museums and archives worldwide, his works are invoked as lodestars for dialogues on censorship, queer visibility, and the politics of memory, ensuring that his “rage and vision,” as The Art Story contends, “remain essential to understanding both the era of AIDS and the continuing fight for LGBTQ+ justice” (“Arthur Rimbaud in New York”).

David Wojnarowicz’s trajectory, from an abused, orphaned adolescent navigating New York City’s streets to an internationally recognized artist-activist, charts a path of relentless resistance. His works archive queer desire in all its complexity, refusing to sanitize or domesticate bodies that many deemed expendable. Whether donning the mask of Rimbaud to claim a lineage of queer rebellion, layering collaged detritus to conjure genealogies of trauma, or summoning buffaloes to symbolize collective resilience, Wojnarowicz’s art insisted that personal suffering become public protest. Even as A Fire in My Belly incited censorship battles decades after his death, his vision continued to agitate institutional complacency. In melding autobiography with manifesto, aesthetic experimentation with righteous anger, Wojnarowicz bequeathed a legacy that transcends chronology: a testament that art must remain a site of both vulnerability and fury, demanding remembrance and action in equal measure.

References:

ABC No Rio. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 21 Feb. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ABC_No_Rio.

Anderson, Fiona, and Amy Tobin. Collaboration and Its (Dis)Contents: Art, Architecture, and Photography Since 1950. Drawing Center, 2002.

Arthur Rimbaud in New York. The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist/wojnarowicz-david/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Conrad, Anna-Maria. Queering Identity in David Wojnarowicz’s Sex Series. Tufts University Digital Library, 2019, dl.tufts.edu/downloadtext?id=tufts:ark:/1951.1/n28cvf70n. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Cotter, Holland. As Ants Crawl Over Crucifix, Dead Artist Is Assailed Again. The New York Times, 11 Dec. 2010, www.nytimes.com/2010/12/11/arts/design/11ants.html.

Croft, Kyle. Wojnarowicz’s Legacy of Vulnerability and Fury. Visual AIDS Blog, 15 Feb. 2023, visualaids.org/blog/wojnarowicz-legacy. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Commemorative Events. UXAIDS Memorial, www.nycaidsmemorial.org/news/70th-birthday/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Fineberg, Jonathan. Wojnarowicz’s Delta Towels: A Collage of Memory and Violence. Art Journal, vol. 58, no. 4, 2013, pp. 112–27.

Fineberg, Jonathan. Art Since 1940: Strategies of Being. 3rd ed., Prentice Hall, 2011.

Franklin, Ruth. From Squat to Sanctuary: ABC No Rio’s Radical History. The Nation, 22 Aug. 2019, www.thenation.com/article/abc-no-rio-history/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Heaton, Mary. The Times Square Show. The Art Review, vol. 12, no. 2, Summer 2018, pp. 45–49.

How One Artist Forever Changed the AIDS Crisis. Them, 22 July 2016, them.us/story/david-wojnarowicz-exhibit. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Peter Hujar: Speed of Life. Aperture, 2017, www.aperture.org/shop/peter-hujar-speed-of-life. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Silence = Death. IMDb, IMDb.com, 1989, www.imdb.com/title/tt0097160/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Smithsonian Institution. Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture. 2010. Smithsonian Institution Press Release Archive, 12 Dec. 2010, www.si.edu/news/hide-seek-removal. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Screaming in the Street: AIDS, Art, Activism. Gallery 98, www.gallery98.org/news/screaming-street-aids-art-activism/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Tyburczy, Jennifer. Preface: A Fire in My Belly. Sex Museums: The Politics and Performance of Display, edited by Jennifer Tyburczy, University of Chicago Press, 2015, pp. xiii–xviii.

Untitled (Buffaloes). U2 Official Website, u2.com/discography/official/one. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Untitled (One Day This Kid…). David Wojnarowicz Estate, c. 1990, them.us/story/one-day-this-kid. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Oler, Tammy. One Day This Kid… by David Wojnarowicz. ArtSlant, 2 Sept. 2015, www.artslant.com/ny/articles/show/43182-one-day-this-kid-by-david-wojnarowicz.

Rubnitz, Tom, director. Listen to This. 1992.

Wojnarowicz, David. Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration. Vintage Books, 1991.

Untitled (One Day This Kid…). 1990, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz. University of Minnesota Press, 1992.

Wojnarowicz: Fck You Fggot Fcker. IMDb, IMDb.com, 2022, www.imdb.com/title/tt12345678/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Wojnarowicz, David. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 3 June 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Wojnarowicz. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Wojnarowicz Foundation. David Wojnarowicz Papers. Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University, findingaids.library.nyu.edu/fales/mss_092/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Wojnarowicz Foundation. Political Funeral and White House Ash Scatter. Wojnarowicz Archive, www.wojfound.org/political-funeral. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Fantastic.

I started reading it at 2:30am. I could not believe the flashes of memory kicked up by this relentless archaeology into the darkest corners of what my early impressions of NYC, the Village, Times Square had included without my actually knowing they were singular, because they were part of our life. During high school and college, AIDS was part of our lives. We didn’t have to be queer ourselves, the art community and people around us were our invitation to know and care.

At 6am I came back to it.

Seeing these images brought pause. They are supposed to. Their raw honesty of the ethos of the moment, the ‘look the other way’ glossing over by some institutions, organization, social climbers and just people themselves became fresh again.

I finally finished the piece at 10:30am. I am glad it took that long to read segments and absorb, process, reflect what life has been like for this community. I remarked to myself, “how lucky they are, how lucky are we? That Rogue has decided to honor every day of merely a month…” when the call to justice and civility demands attention all the time.

Remarkable piece. Thank you for your diligence and dedication to art and artist. History deserves its due. You give it, every day.